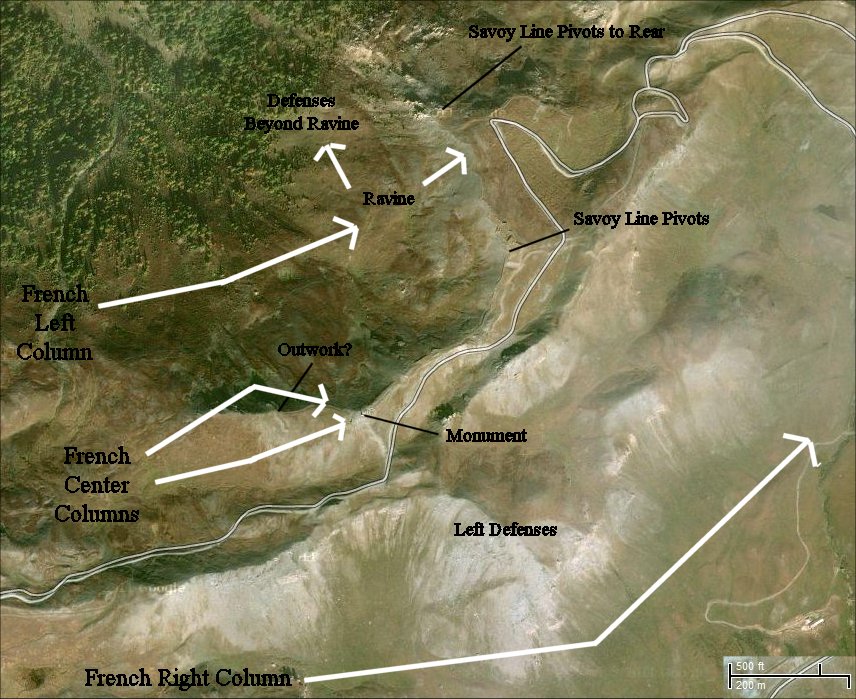

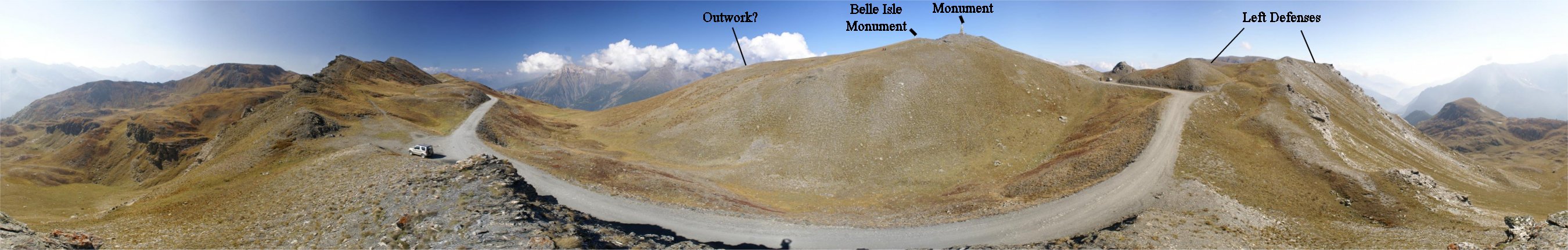

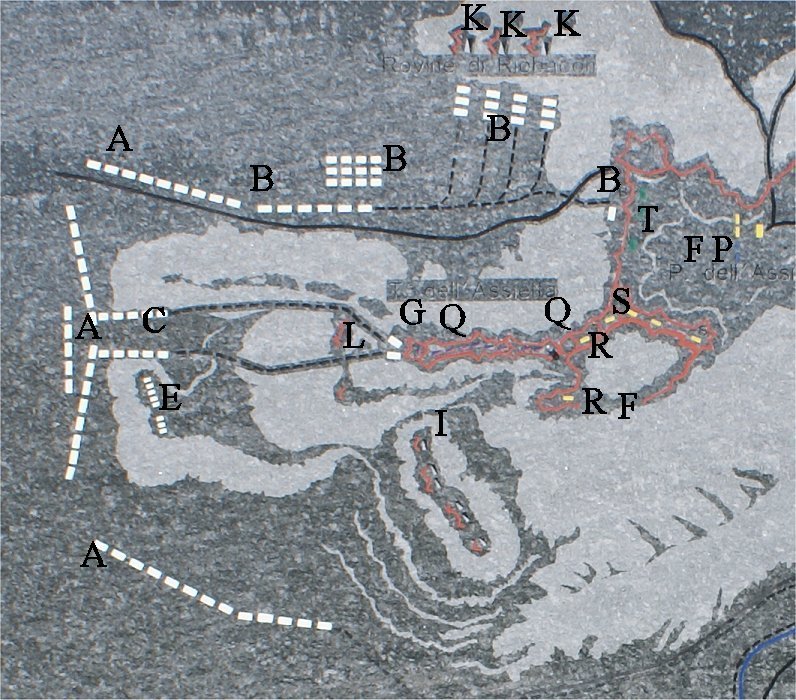

On the map, the Savoy army entrenchments are in red. The French right column of 14 battalions under the command of Marshal Villemur swung wide to the right and around much of the enemy position to attack it on another section of the mountain. The effort failed. On the map this is the column on white troops on the bottom.

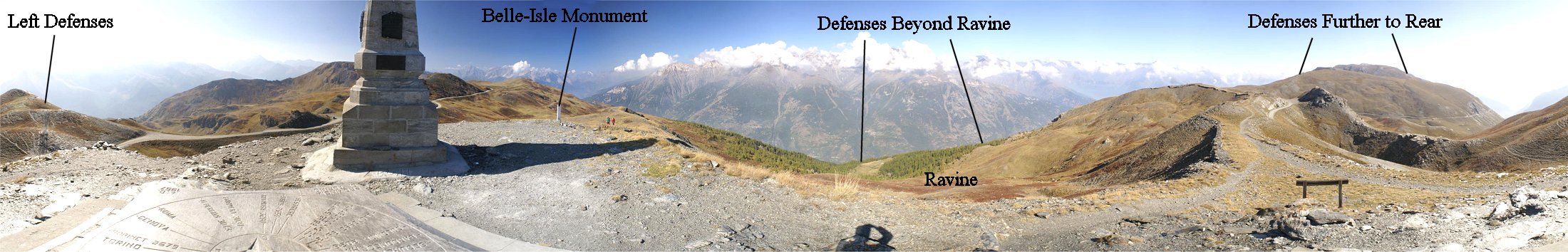

The French left column of 9 battalions under General Mailly was to move through a ravine and attack the enemy position.

The French center column of 8 battalions under Marshal d'Arnaud was to attack the salient to their front. At 4:30, the French attacked.

A site from which came the four French columns

B first column

C two columns of the center

E French battery

F entrenchment of the hill 'Assietta

G attack on grenadier guards. Belle Isle and d'Arnaud killed

I -K reduced defense volunteers

P Austrian Colloredo and Casale Piedmontese

Q entrenchment defended by the regiment of grenadier guards

R Hungarian battalion Forgatz

S Austrian Traun Battalion

T Swiss battalion Meyer