Charleston

May 12, 1780

By 1779 lack of success in the North and French intervention

forced the British to rethink their strategy. The

South was wealthier than the North, and the capture of a major port

would help the naval war against France. The rich rice producing

lowlands would better support an army and allow for more active

campaigning. Loyalists were more numerous in the South and might

be encouraged to join the cause. Savannah, Georgia had already

been captured, but attempts on Charleston had been so far repulsed.

A larger army with proper naval support might be successful,

however.

Sir Henry Clinton left Sandy Hook outside of New York harbor on the day

after Christmas, 1779, with 8,700 men. Storms scattered

ships and even sank some. Most of the horses were lost, and one

ship was even blown clear across the Atlantic. A majority of the

ships, however, were off the Georgia coast near Savannah by the end of

January 1780. Clinton sent 1,400 men, including his cavalry on a

raid into the Georgia interior and proceeded by sea to

Charleston.

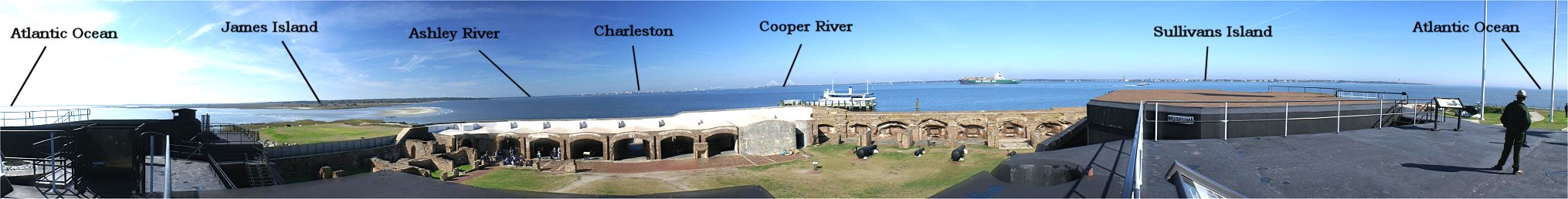

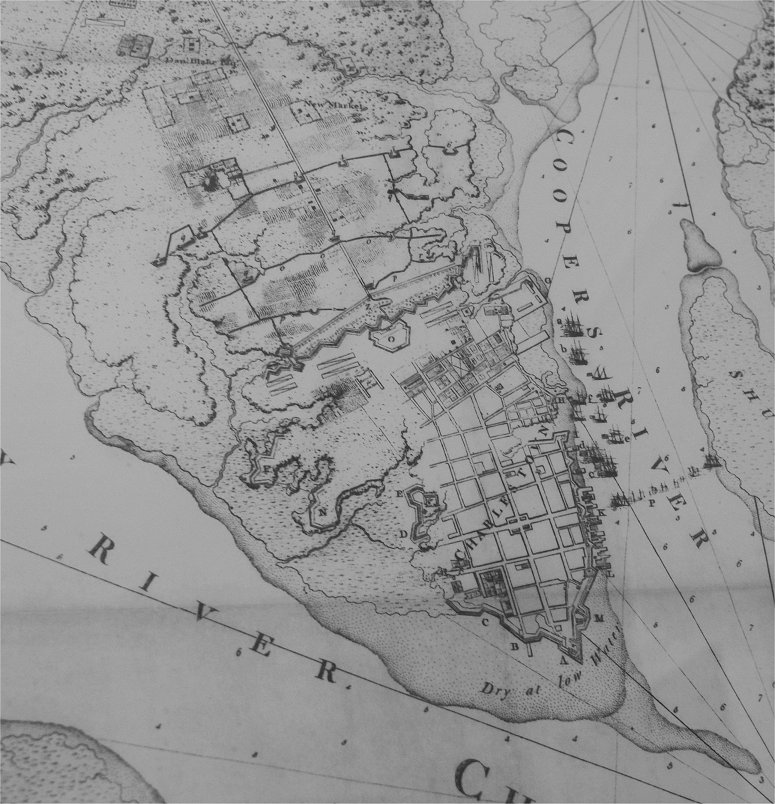

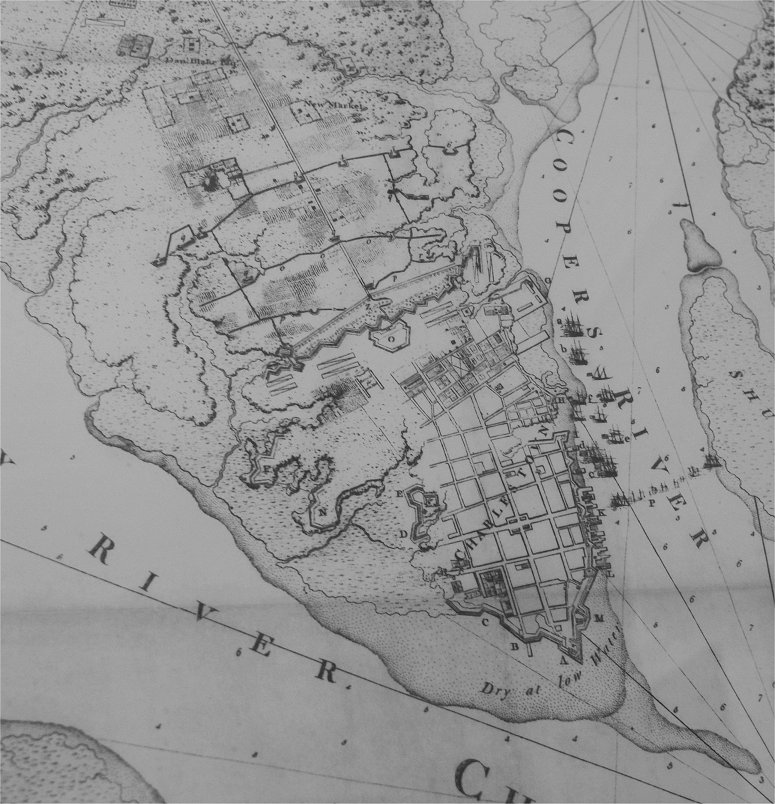

Charleston Harbor

Clinton had commanded the failed 1776 expedition to Charleston, so he

was familiar with the difficulties of capturing the place. The

channel into the harbor followed the coast north until reaching the

harbor entrance. This channel was narrow and could be defended by

a smaller naval force at the bar. If a naval force got to the harbor

entrance, it had to deal with shoals where Ft Sumter would later be

built, and with guns at Ft Moultrie on Sullivan's Island. Once

these obstacles were passed, there was an additional shoal in the

harbor and guns at Ft Johnson on James Island and in Charleston itself.

The American army in Charleston had 3,600 men under Maj Gen

Benjamin Lincoln. Commodore Whipple commanded eight

warships.

On the advice of a Captain Elphinstone of the Royal Navy, Clinton

decided on an approach up the North Edisto Inlet in order to land

on modern Seabrook Island, just south of John's Island, which was done

on February 11th, just in time to escape another bad storm. James

Island was taken in the coming days, and a bridgehead was established

on the mainland across the Stono River. On March 20th the Royal Navy crossed the

bar and entered the shipping

channel, and in the coming days, the detachment that had raided Georgia

arrived. Clinton was now near to Charleston as the crow flies,

but still separated by the Ashley River, which was a formidable

obstacle on its lower reaches. The Americans were expecting a

crossing near Ashley Ferry. Instead, on the night of March 28th

and 29th, Clinton had 75 flatboats quietly rowed further upstream

to cross at Drayton Hall.

Drayton Hall

The Drayton family was involved with revolutionary politics, so it

should come as no surprise that the British made use of the family

furniture - outdoors.

Here, behind Drayton Hall, the British crossed the Ashley River,

paddling a mile upstream to land on firm ground. The only

American defenders in sight were some dragoon, and an American redoubt

was found undefended. Clinton was now 12 miles upstream from

Charleston, and the most obvious American escape route was closed.

On March 30th, Clinton marched on Charleston, and on April 1st, he

broke ground on siege lines. On April 8th, the Royal Navy passed

Ft Moultrie and successful brought Clinton supplies he needed for the

siege. The Charleston defenses were formidable - 66 American guns,

two lines of abatis, a canal serving as a moat, and a stone hornwork in

the center of the line, so when Clinton asked Lincoln to surrender on

the 10th after comleting the 1st parallel, the American predictably

declined. A 2nd and a 3rd parallel would be dug, but Clinton had

yet to complete the encirclement.

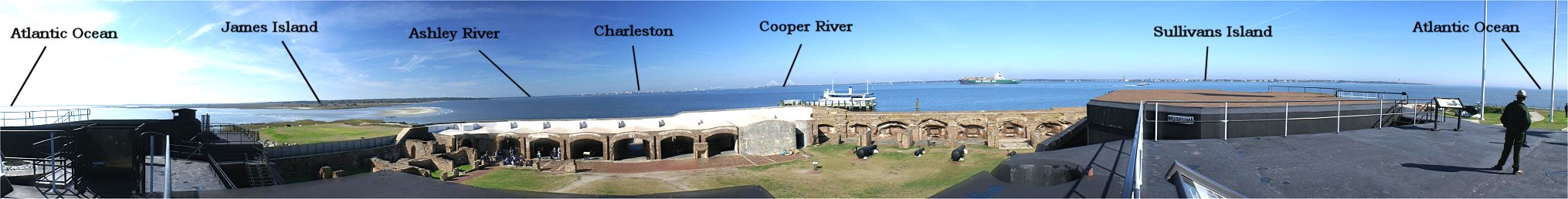

From Patriot's Point

This is the view from the north side of the Cooper River, modern day

Patriot's Point. Castle Pinckney, then Shute's Folly, is the dark mass below the

sunset at left. The American fleet was in the river behind a log

boom between Shute's Folly (modern Castle Pinckney) and Charleston

while the sailors manned guns ashore protecting the city. The

British main camp was on the peninsula in the area of the modern

suspension bridge. Clinton sent a portion of his force upstream then across the

Cooper River to cut off American supplies and reinforcements coming

from the north. The Brits won a victory at Monck's Corner on

April 14th, and by the 25th, the British marines occupied the riverbank

across from Charleston, Lempriere's Point, beyond the modern

suspension bridge, and Hadrell's Point, which is off the panorama

to the left. The marines were later replaced by army troops.

On May 7th, Ft Moultrie was taken by marines.

The garrison of Charleston was now trapped, with the only hope

being a breakout. Civilian leadership had opposed evacuation,

and now that evacuation was impossible, they opposed a break out.

Hornwork

A small portion of the hornwork, or citadel, protecting Charleston

still remains. There are no other modern reminders of the siege.

On April 24th, an American sortie damaged some of the British

works, but they were repaired and work continued. On May 1st,

the British sap reached and began destroying the dam

that kept water in the American ditch. Meanwhile, the

British were also digging the 3rd parallel. Rifle fire was taking

a toll in the American trenches even through the gap of just

a few inches between the parapet and the sandbags that had

been placed above the parapet. Although the British troops

were eager to storm the town, Clinton was not, so on May 8th, he sent

another summons to surrender. With the situation clearly

hopeless, Lincoln entered into negotiations, but he rejected the harsh

British terms. The siege continued on the 9th, and the British

saps continued forward through the American abatis to within 30 paces

of the American lines. On the 10th, the militia abandoned the

trenches and could not be persuaded to return. The next day, the

civilian authorities made it known that it was time to surrender.

Many of the American guns had been disabled, the city had been

bombarded. Meat was scarce. So on the afternoon of the 11th,

the white flag was shown, and Lincoln made it known that he would accept

Clinton's previous offer. The American regulars, only 1,500

to 1,600 Continentals weren't sick, marched out and laid down their

arms the next day. They would become prisoners of war. The

militia laid down their arms in town. They were paroled. After the surrender, an

explosion of gunpowder in Charleston near a poorhouse and a

whorehouse caused many needless casualties.

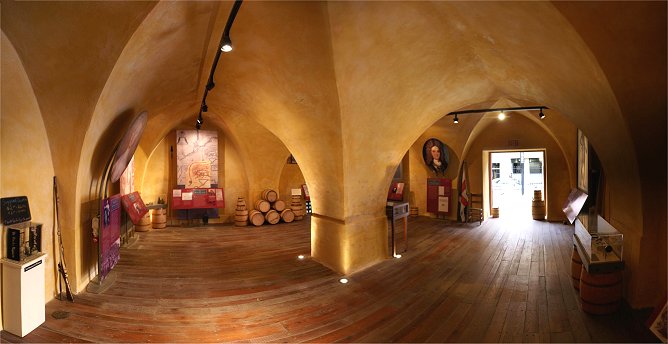

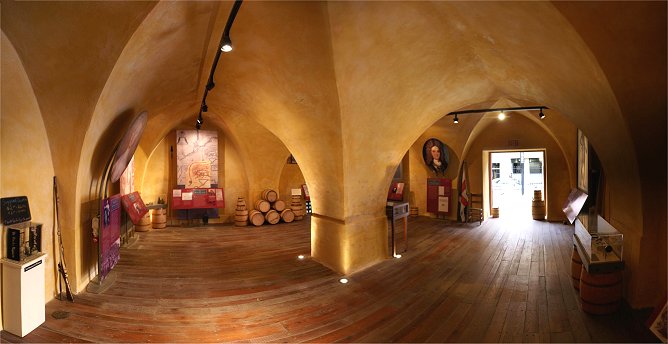

Powder Magazine

Exchange Building

Not all the powder was blown up. Before the surrender, Gen

Moultrie had gunpowder taken from Charleston's Powder Magazine and

placed under the Exchange Building and bricked up. British

headquarters were located in the building until evacuation in 1783, but

the powder was never discovered.

Waxhaws May 29, 1780

The British moved inland to occupy the colony. Lt Col Banastre

Tarleton with the British Legion pursued, and on May 29, caught a

Virginia infantry battalion under Col Abraham Buford at Waxhaws.

The

British cavalry charged into the patriot infantry line,

which waited too late to fire. Tarleton's victory was total.

With

the loss of only 4 killed and 13 wounded, Tarleton killed 113

Americans and wounded or captured 203. Of these 203 captured,

150 were too wounded to be moved. In a typical battle of the era,

there would be four or five times more wounded than killed.

Tarleton gained the reputation

of not taking prisoners, and the butchery at Waxhaws would provoke many

reprisals. The war in the South would become a brutal affair.

Rice Paddy at Middleton Plantation and Indigo at a Charleston Garden

Clinton left the Carolinas, returning to New York and leaving

Cornwallis in command in the South. South Carolina was now largely defenseless

to British invasion, and many people, out of either genuine loyalty or

simply out of self-preservation, proclaimed their loyalty to the King.

A wealthy colony with an abundance of indigo and rice, South

Carolina might provide adequate supplies and funding for active

campaigning year round. North Carolina and Virginia were

poorly protected, and George Washington's northern army would soon

be dealing with problems like Benedict Arnold's attempted

betrayal of West Point and the mutiny of troops

from several states. With everything in their favor, why

did the British fail in the South?

Exchange Building - British Headquarters

The British failed in the South for the same reasons

they failed in the

North. Like in the North, the Loyalist population of the

South was not as numerous as had been believed. As in the

North, British depredations, primarily those of foraging

parties, lost the King friends. Events like the 'Waxhaws

Massacre' became American propaganda victories. And on June 3rd,

before Clinton departed, he issued a proclamation stating that those

who did not return to their allegiance to the king would be treated as

enemies and rebels. You were either with the British or you were

against them. Forced to choose, many men sided with the

rebels. Organizing guerilla bands, they were no match for

regulars, but they hindered British supply and forced the British to

disperse their troops across the colony in an effort to control it.

If the patriots could form another regular army, perhaps the

South could be liberated. Just such an army, under the 'Hero

of Saratoga', Horatio Gates, was being

organized to oppose the redcoats. It would strike at a British

outpost

at Camden in August.