In May 1744, the French army invaded the Austrian Netherlands and successfully besieged the Flemish towns of Menen, Ieper, Furnes and the fort La Kenoque.

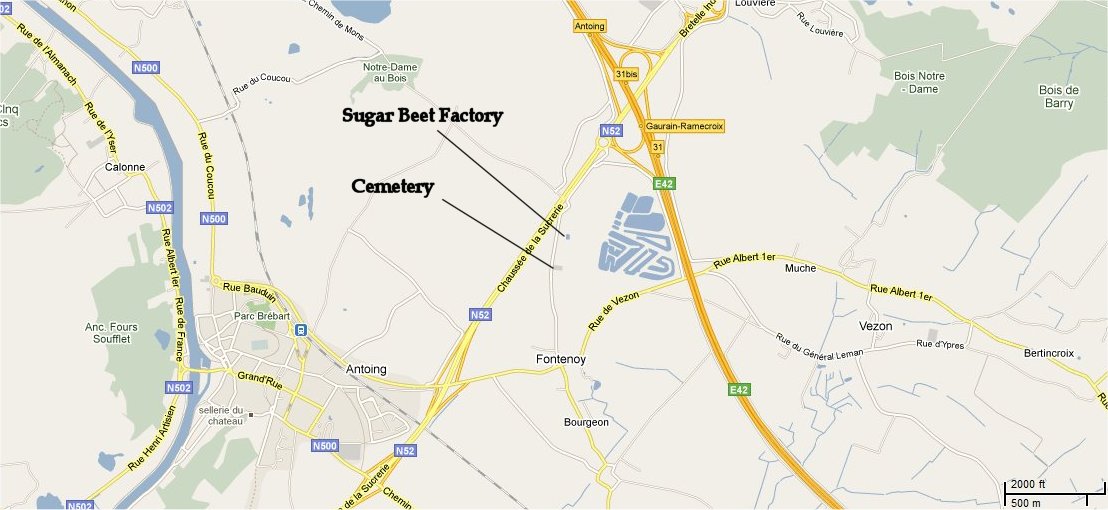

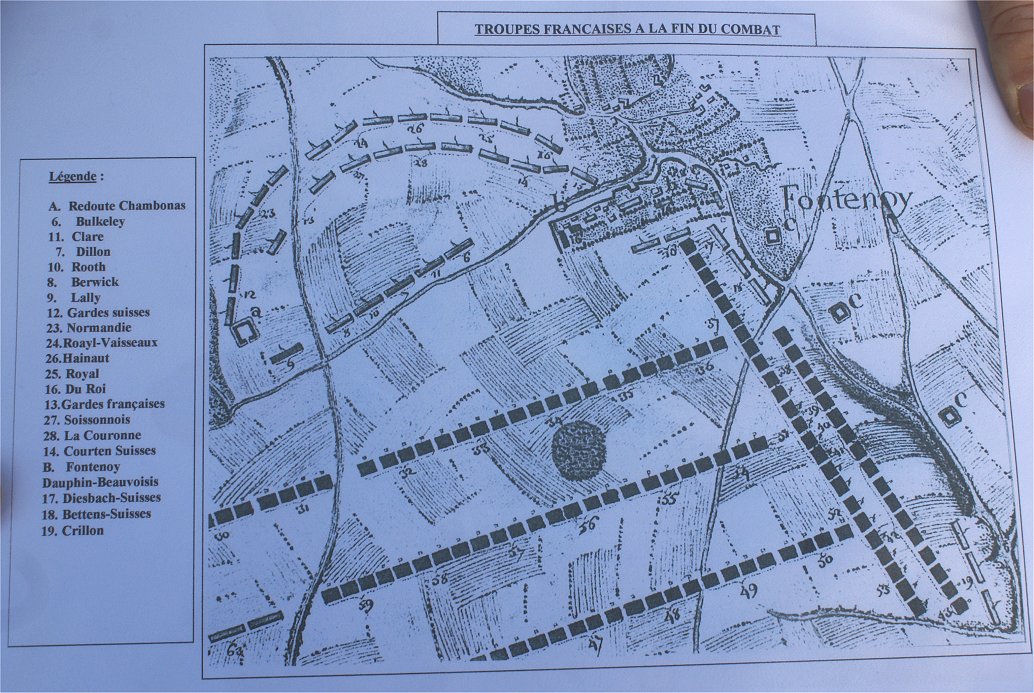

By 1745, a French army under Maurice de Saxe was poised to invade the Austrian Netherlands, roughly today's Belgium. De Saxe was a royal bastard, in a literal sense, the illegitimate son of the King of Poland / Elector of Saxony. De Saxe had fought for several monarchs but was now a high commander for Louis XV of France, who was accompanying his army. He was also the leading military thinker of his time. Although French artwork of the battle shows him healthy and vigorous, at the time he was in poor health, having had fluid drained and getting around by curricle, a small two wheeled cart drawn by horse. Opposing him was an allied army, the "Pragmatic Army" composed of Brits, Hanoverians, Dutch, and 'Austrians' under the Duke of Cumberland, the son of King George II of England. De Saxe seized the initiative, feinting toward Mons but besieging Tournai and its 8,000 man garrison on April 26th. Capture of Tournai would open up the Austrian Netherlands to further advances and threaten British communications with the coast, making the city excellent bait for the Pragmatic Army. Learning that the enemy was to the southeast, he left 21,000 men to besiege Tournai while taking the remaining 48,000 men to Fontenoy, beyond the Scheldt River, to cover the siege.

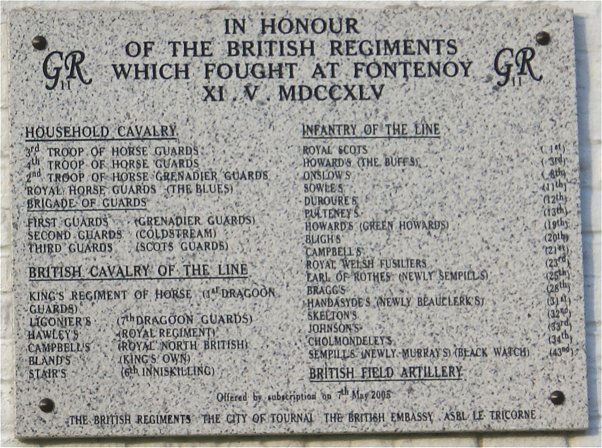

Maurice de Saxe