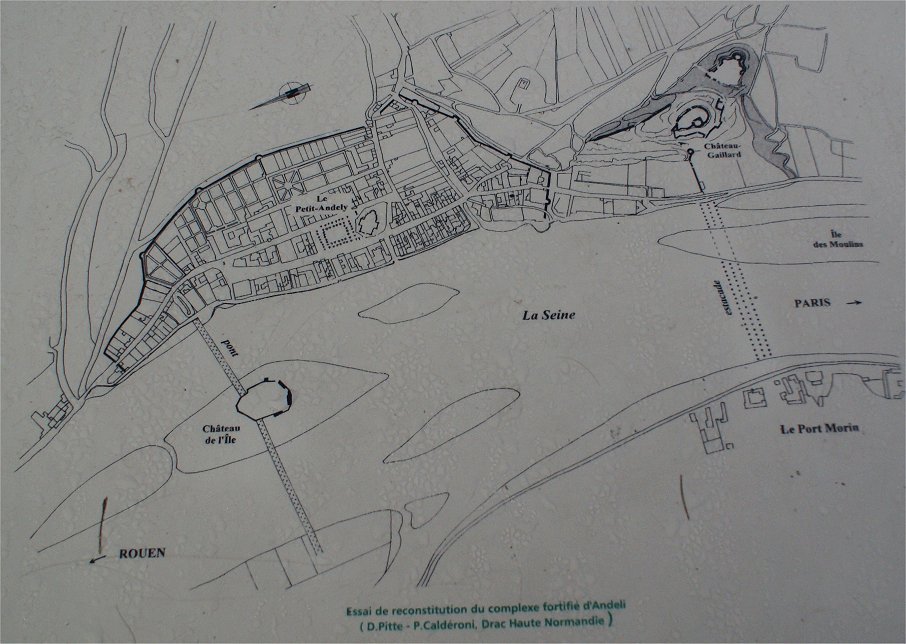

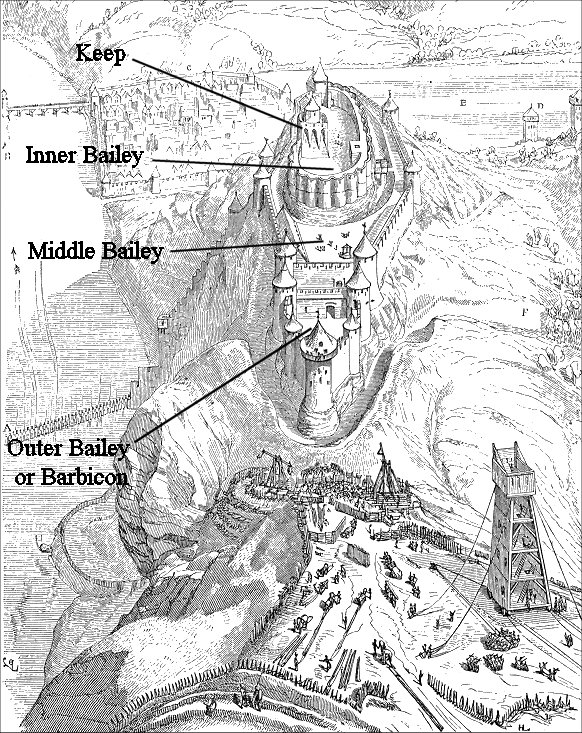

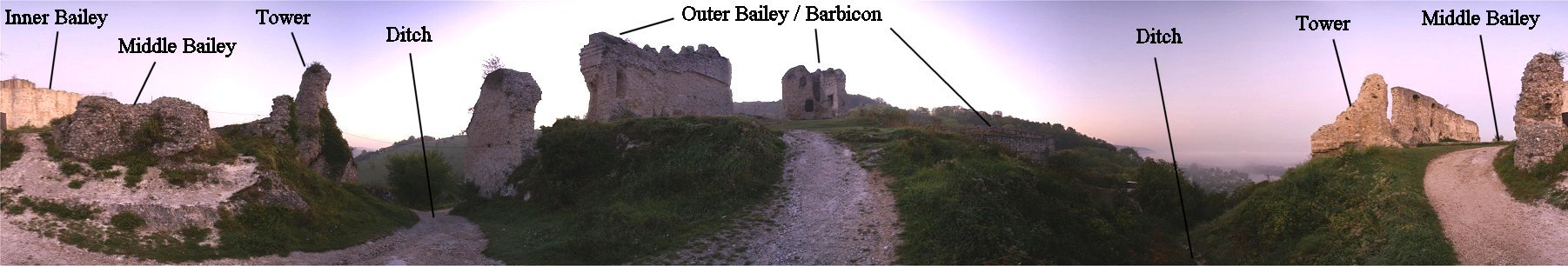

In the late 1100s King Richard the Lionhearted of England and King Phillipe Auguste of France briefly ended their conflict in Normandy with a peace treaty. Richard, however, in 1196 began construction of a castle, Chateau Gaillard, in a designated neutral zone along the River Seine, a place called Andeli, an act which gave him control of river traffic from the Channel into Rouen and Paris.

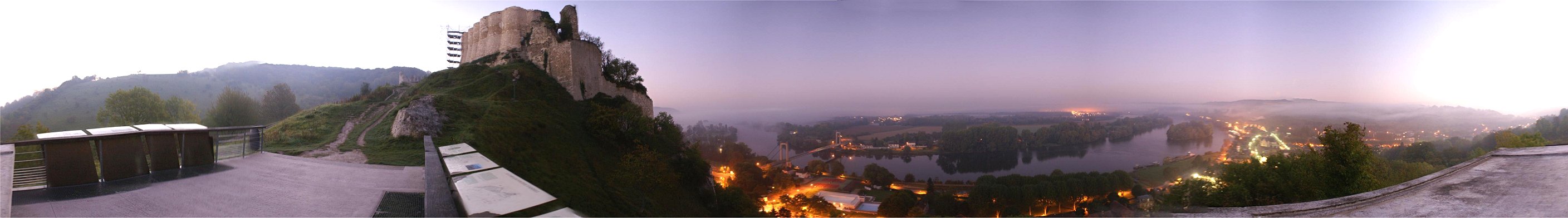

After Richard died and was succeeded by King John, Phillipe Auguste attacked the new fortifications, capturing the Chateau de Ile then the town itself, forcing the residents to seek the protection of Chateau Gaillard on the cliffs 90 meters above the river.