Hawthorn Crater

Hunter-Weston's VIII Corps extended south to Beuamont Hamel, another of

its attack objectives. Here, the regular army 29th Division would

attack, aided by the blowing of a 40,000 pound mine beneath the

Hawthorn Redoubt. A veteran of the Gallipoli campaign,

Hunter-Weston did not have a great reputation. For the first day

of the Somme he hoped to blow the mine at 3:30 then sieze the crater -

this a full four hours before the main attack. This would have

completely eliminated the element of surprise, so this plan was not

well received. The man in charge of the mine recommended that it

be blown at 7:30 as the attack began. Eventually a compromise of

7:20 was decided on. This, of course, alerted the Germans of the

impending attack. Simultaneously the artillery bmbarment was

shifted tot he German second line, leaving the German infantry ten

peaceful minutes to prepare for the attack. As was true

elsewhere, counterbattery fire had left the German artillery largely

intact and ready for battle.

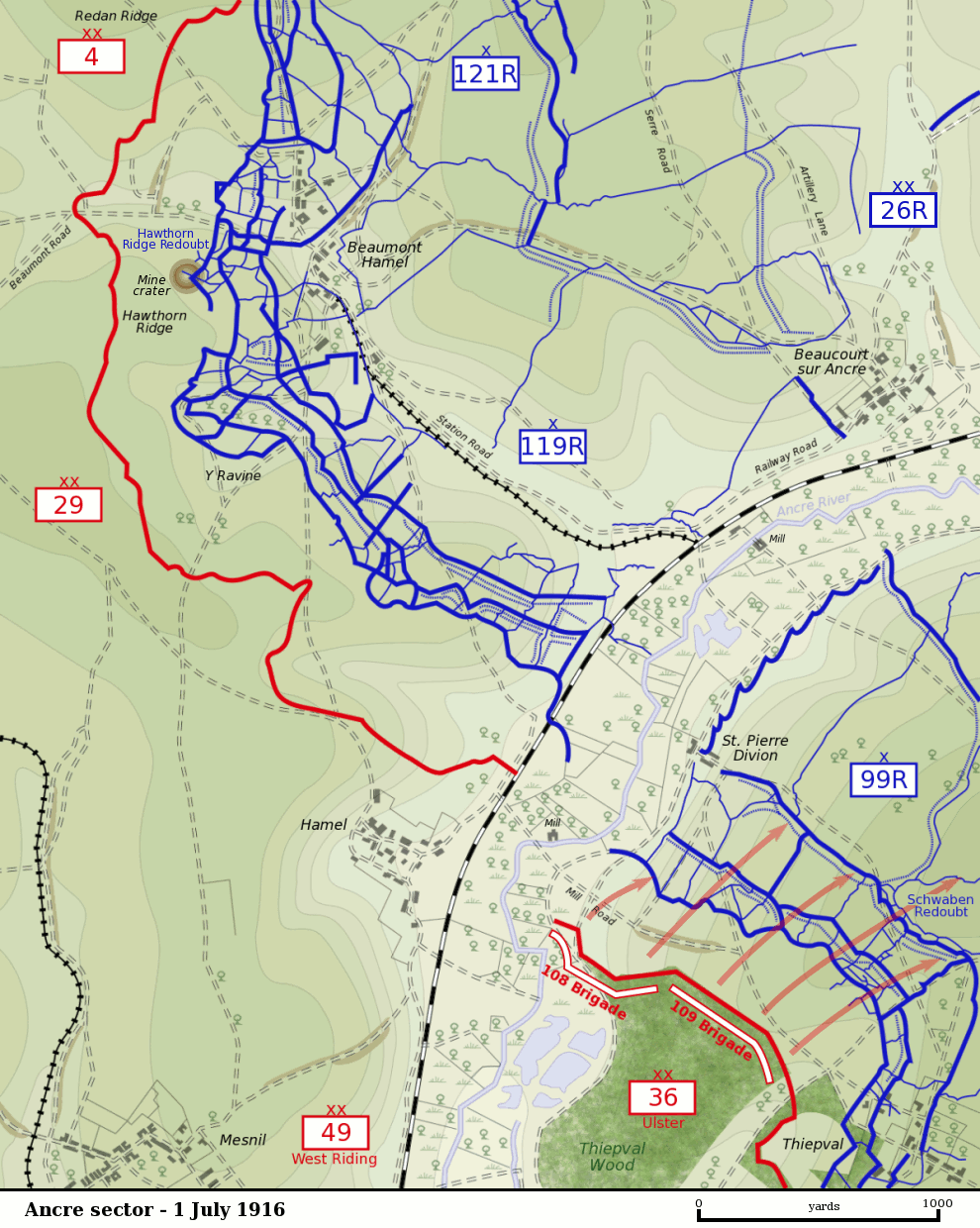

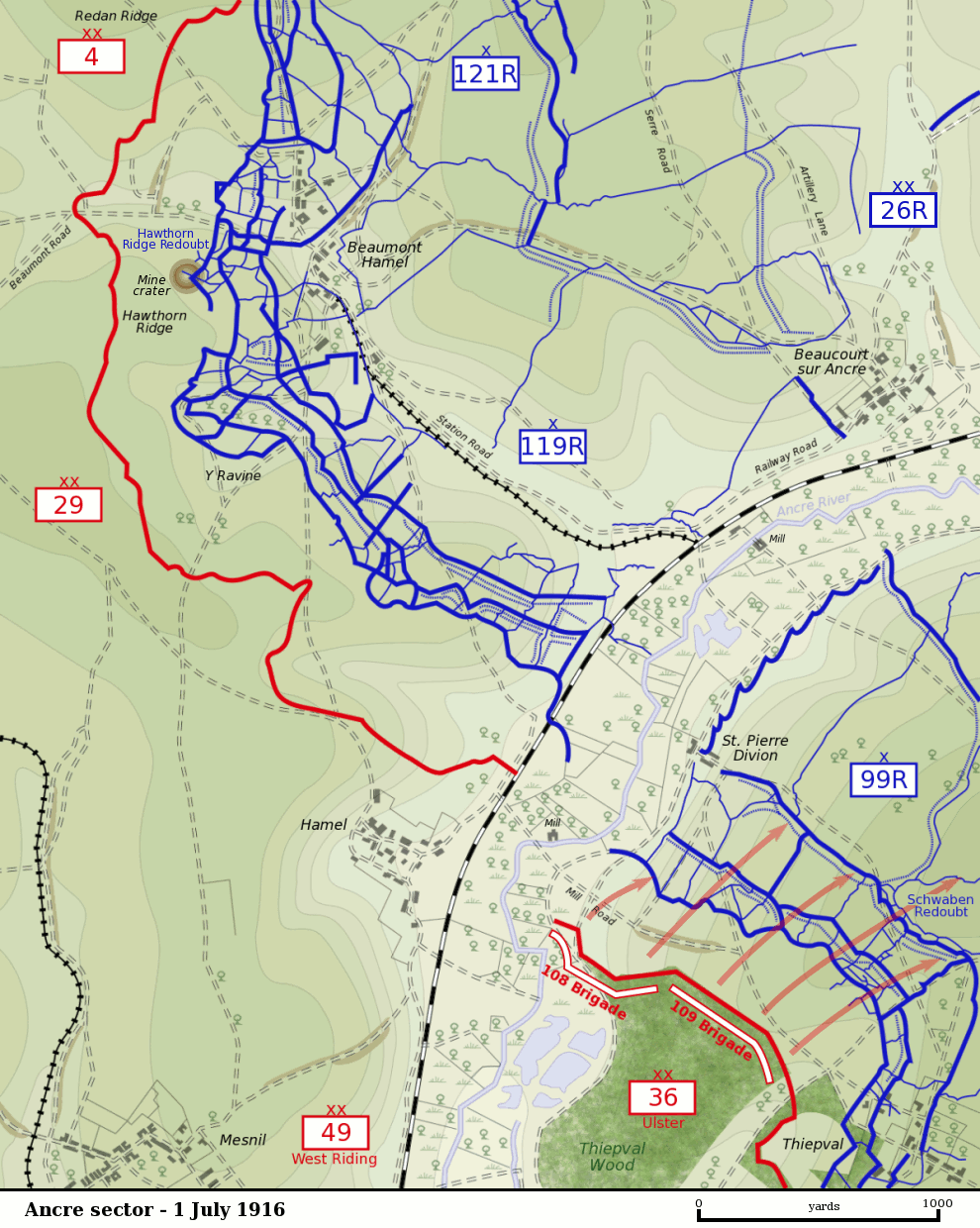

This map from Wikipedia shows the area well. At lower right is

the 36th Division's attack, which will be shown in another section.

The blue line is the approximate German front line. The British

attacked from the west - the left of the map. A,B, and C

correspond to the panorama locations below.

A) Hawthorn Crater

The explosion of the mine was recorded by motion picture, and if you do

a Youtube search of "Hawthorn Mine", you can likely find footage.

The explosion blew three German sections skyward and opened up a

white, chalky crater 50 yards wide and 60 feet deep. Surviving

Germans raced out of their dugouts, sure that a British attack was

imminent. In the immediate aftermath of the explosion, and ten

minutes before the main attack, two British platoons with machine guns

and mortars with rushed forward to capture the crater.

The Germans reacted quickly, however, and were closer, so they

reached the eastern edge of the crater first. Reaching the

western edge of the crater, the British found the Germans on the

opposite side. Exposed to enemy fire from their flanks, the

British had no hope for securing the destroyed German strongpoint.

Soon, the main attack began. With much of the German barbed wire

still intact, the attacking British infantry took heavy losses.

Some of the dead from the fighting near the crater were buried in

the Hawthorn Ridge No. 1 Cemetery.

The British and German lines were not close. For example the

motion picture photographer's position was the approximate British

front line, a good 1,500 feet from German lines opposite in a small

wood lot indicated on the panorama. White City was an area held

by the British that hidden from German view by chalky white piles of

earth and rock. In no man's land the only significant cover for

the attacking troops was a sunken road. We will go there next.

B) Southern End of Sunken Road

The axis of advance of the attacking troops of the 29th Division was

from the direction of Auchonvillers toward Beaumont Hamel. The

Brits had tunneled from their front line forward to the Sunken

Road. Via tunnel the 1st Lancashire Fusiliers moved to the sunken

road to attack the German held wood lot to their front. (Some

times of the year you may be able to make out where the tunnel

emerged.) The Lancs couldn't see the German lines from the sunken

road, and they never reached the German line. A singleThe unit

lost 18 officers and 465 men that day. Although the sunken road

was evacuated, it was later re-occupied and incorporated into the

British trench system.

Next we continue through Beaumont Hamel and into the German rear.

C) End of Y-Ravine

Here at the civilian cemetery on the southeastern corner of Beaumont

Hamel you can see the end of Y-Ravine, a continuation of the prominent

feature of Newfoundland Park. This was a German rear area with

dugouts and so forth, and the Germans used the ravine to move to and

from the front lines in what is now the Newfoundland Park.

The 29th Division lost 5,240 men on July 1st.

Copyright 2012 by John Hamill