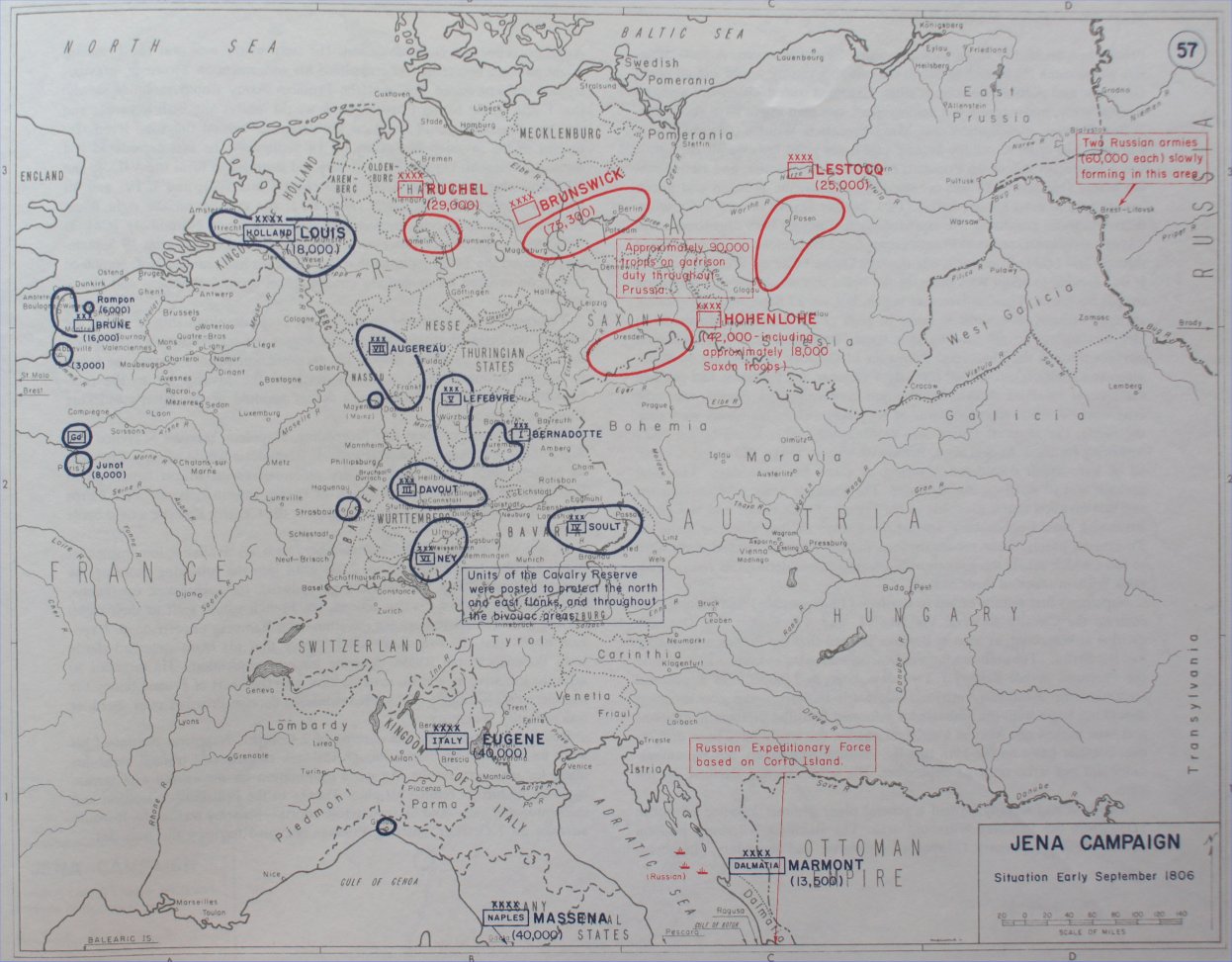

After Napoleon crowned himself Emperor in 1804 the wars continued, and in 1805 Napoleon smashed a combined Austrian and Russian army at Austerlitz, bringing much of Europe under the domination of France. Napoleon's reorganization of the German states into the Confederation of the Rhine rankled Prussia as well as Britain, whose monarch had also been elector of Hanover. Prussia coveted Hanover, but France wanted it as a bargaining chip with Britain. A coalition was formed to fight Napoleon, the fourth such combination of powers. Prussia was joined by Britain, Russia, Sweden, and Saxony - with Saxony strong-armed into the alliance by Prussia.

Napoleon's supply base at Mainz (or Mayence) suggested a French attack from that direction. In truth, Napoleon's supply system was flexible, and he could supply himself from several points while his army for the most part lived off the land. So Napoleon's Mainz base lured the Prussians into sending part of their forces west in an attempt to cut the French lines of communication.