Louisbourg

The 1713 Treaty of Utrecht ending the War of Spanish Succession brought

big changes to Atlantic North America. France was forced to give

up Newfoundland and Acadia - now southern Nova Scotia - leaving them

only Cape Breton Island, known as Isle Royale, and what is now known as

Prince Edward Island. To protect New France and the

Atlantic fisheries, France needed a new naval base in Cape Breton

Island, a place that could also be used for trade and for processing of

fish. Several sites were considered. Ultimately,

however, Havre a l'Anglais was selected, an ice free harbor with plenty

of beach area for fish processing, a place that had been used by

English fishermen; it was renamed Louisbourg. Two engineers,

Verrier and Verville, designed the defenses, which would become the

most impressive of the western hemisphere. A comparable

European fortress would have featured dressed stone, but Louisbourg was

built with rough stone which would prove difficult to maintain in the

difficult climate with freezing and thawing. Implied by many

historians is that the fort should have been entirely earthen.

Agriculture is marginal in the area, and climate and the short

campaigning season were perhaps the greatest

defenses of Louisbourg. The French navy was also a

strong deterent; a British expedition needed overwhelming naval

superiority to succeed, both to blockade the Louisbourg squadron and to

prevent the French from sending a relief expedition. Such were

the difficulties that after the place was captured in 1745, a French

expedition to recapture Louisbourg in 1746 was forced to return to

France without even sighting the town, having suffered thousands of

deaths from disease in the process. In 1757, the difficulty of

mounting a major

amphibious operation

from England, on time, with naval opposition was more than they could

manage for that year - having removed troops from the New

York frontier, the effort was cancelled when it was learned that

the French squadron at Louisbourg was superior.

In 1745, New England

forces supported by the Royal Navy captured the town, but in the peace of 1748 it was returned to

France, an event that angered many American colonists.

In 1758, the town was again captured, this time for good.

The capture of Louisbourg blocked French communication with New

France, and the next year

the British continued to Quebec, which they captured, followed by the

rest of New France in 1760. The peace treaty confirmed the

British

North American conquests, leaving the French only some small islands

for

fishing. The British destroyed

the

fortifications at Louisbourg in 1760 and abandoned the place in 1768.

In the mid

20th century part of the town and fortifications were reconstructed to its 1744 appearance,

making it one of the great historical tourist attractions of North America.

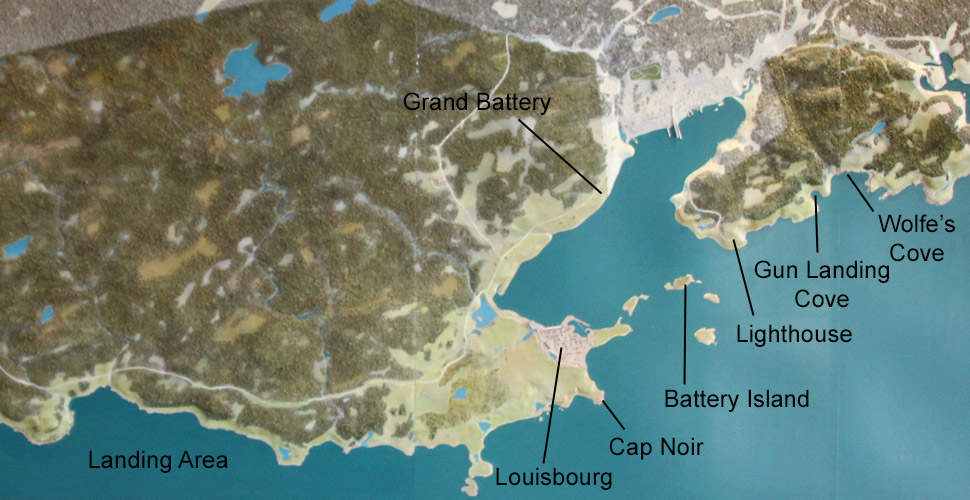

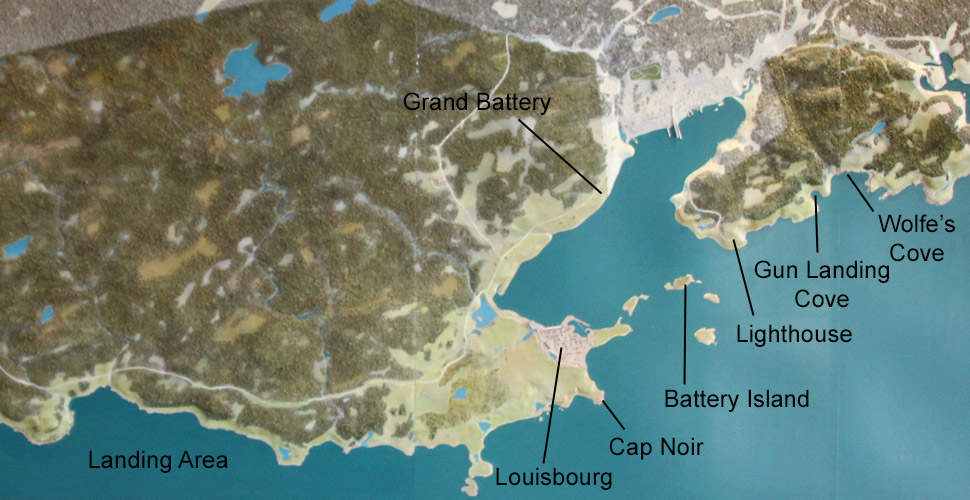

The Americans 1745 and the British in 1758 landed at Gabarus Bay

and pulled cannon across swampy ground to besiege the town.

In 1758 the French contested the landing but were forced back.

They then abandoned the Grand Battery covering the entrance to

the harbor. A force under Wolfe marched to the French battery at

the lighthouse and captured it, getting supplies landed at Gun Landing

Cove

and Wolfe's Cove.

Grand Battery

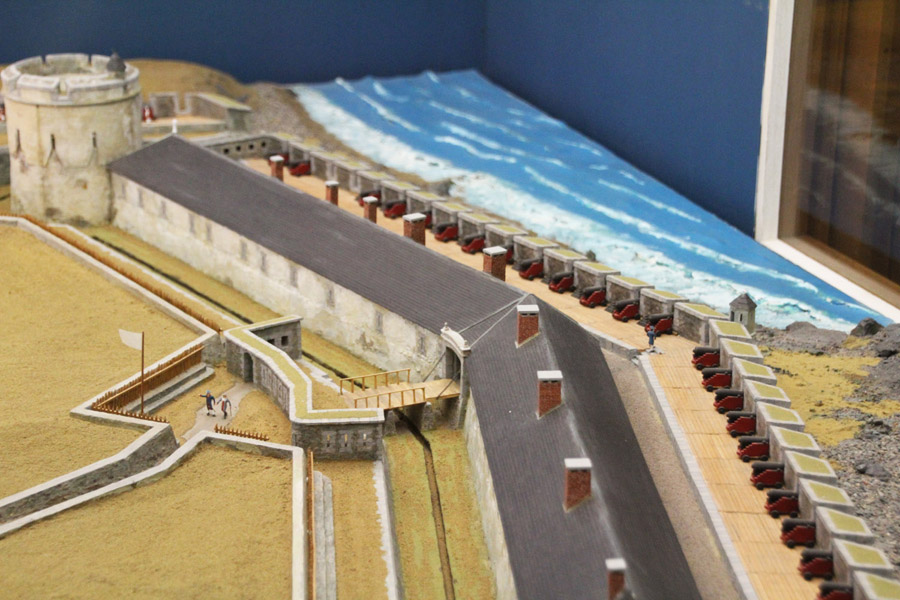

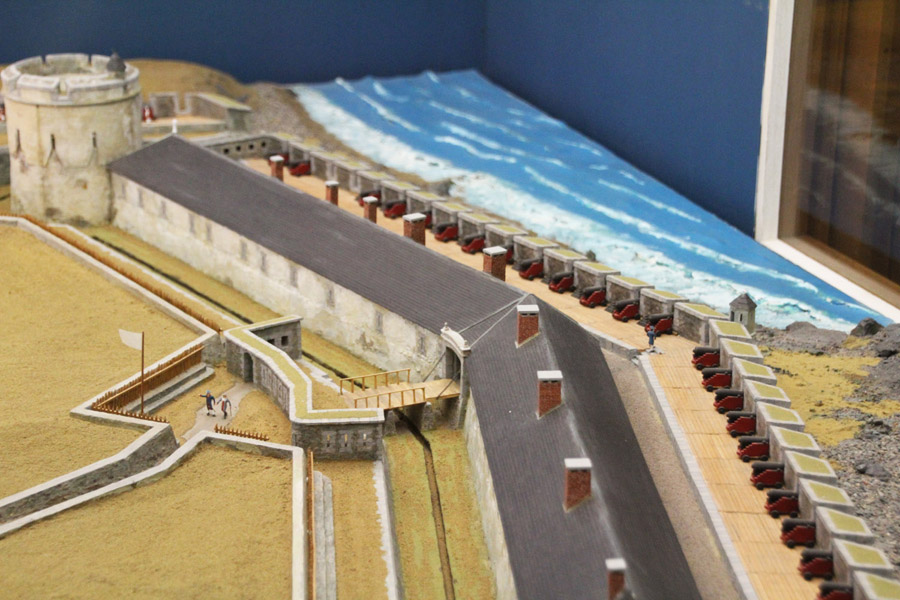

Built between 1724 and 1732 to cover the entrance to the harbor,

fire from here and the Dauphin Demi-Bastion created a crossfire in the harbor. The Grand

Battery had minimal landward defenses, so in 1745, the French

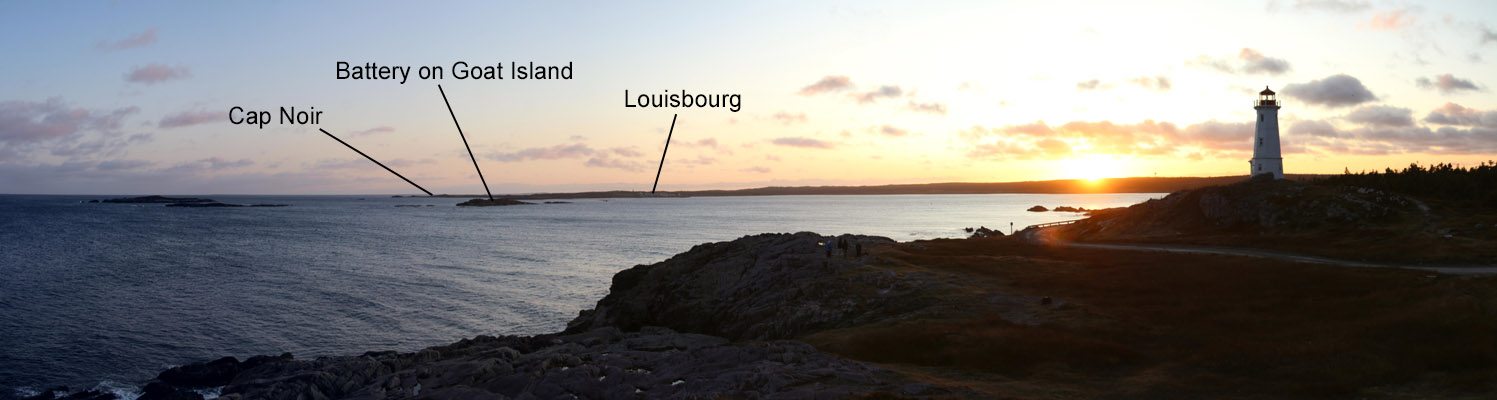

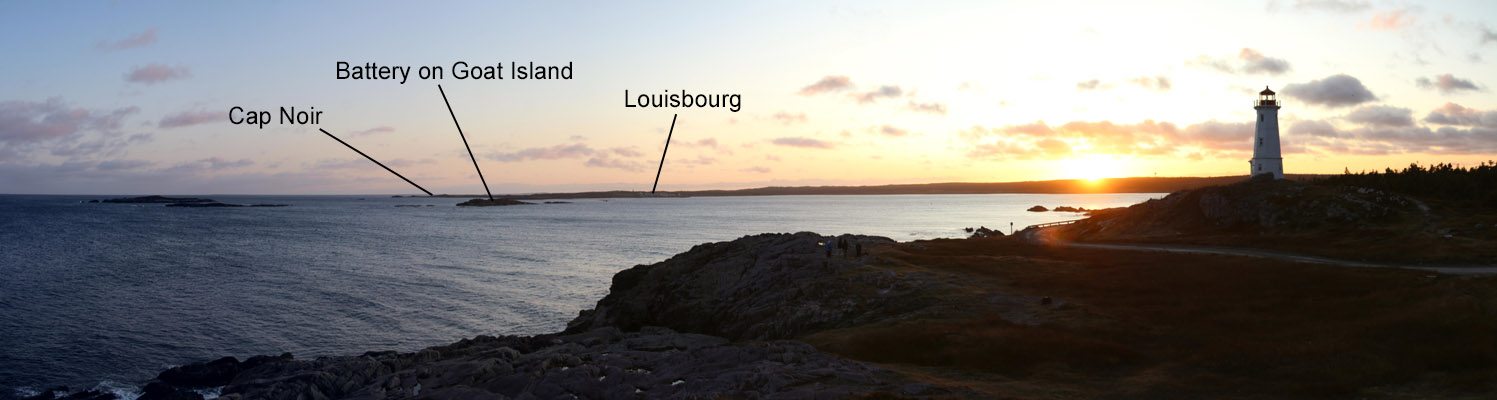

abandoned the battery, and the Americans used its guns against the battery on Goat Island as well as the

town. The New Englanders made a costly attack on the French

battery on Goat Island, but finally forced the island to surrender by

bombarding it from the area of the lighthouse. This, in turn, led

to the surrender of the town.

In the 1758 siege, the Grand Battery was again abandoned, but the guns

were made inoperable. Like in 1745, the British once again

bombarded the Goat Island battery from the area of the lighthouse.

The French ships had to withdraw closer to Louisbourg where they

enchanged fire with British siege lines then with batteries on this

coast manned by the Royal Navy. Several ships were

destroyed, and on July 26th, 600 British sailors and marines captured

two French ships from their skeleton crews. With the town now

under threat from the harbor and with the walls breached, the French

surrendered that day.

Modern Lighthouse

On June 12, 1758, Wolfe with 1,400 men marched from the landing site at

Gabarus Bay to Lighthouse Point. A French battery there was

abandoned with the cannon rolled off the cliff. After

constructing batteries, the British opened fire on the French battery

on Goat Island on June 19th. On the 21st, French warships

withdrew closer to Louisbourg, and on June 25th, the French batteries

were silenced. Facing the threat of the British fleet entering the

harbor, the French sank four ships in the channel on the night of June

28-29.

Gun Landing and Wolfe's Cove

Guns and supplies were landed at two coves just to the east of the Lighthouse.

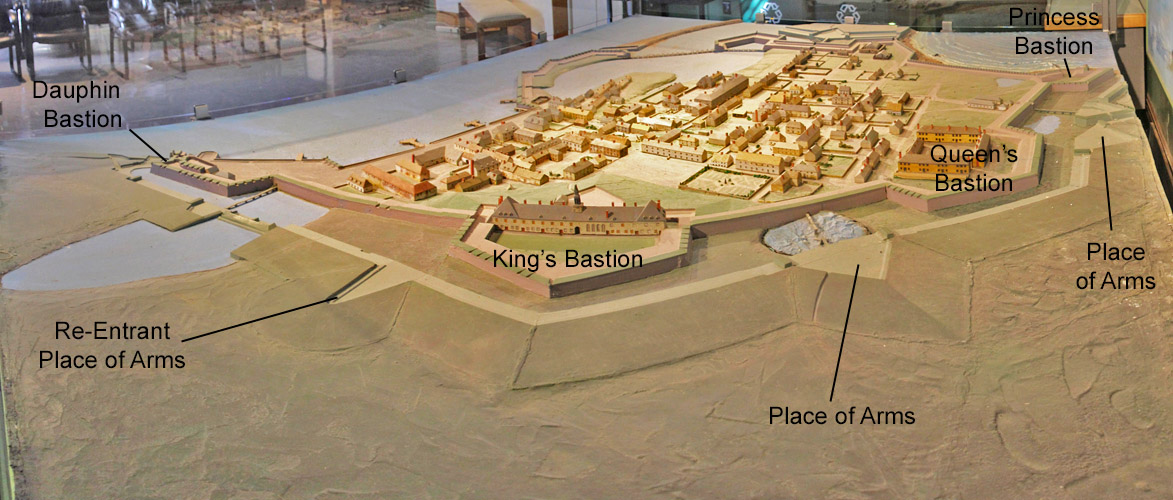

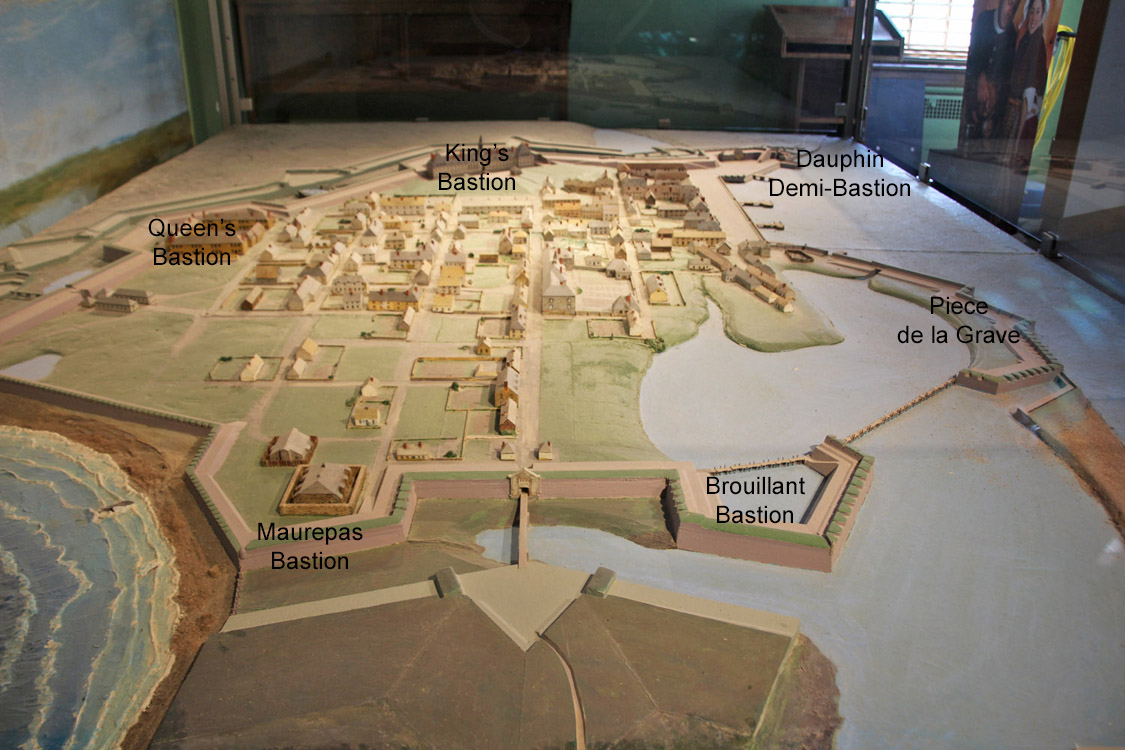

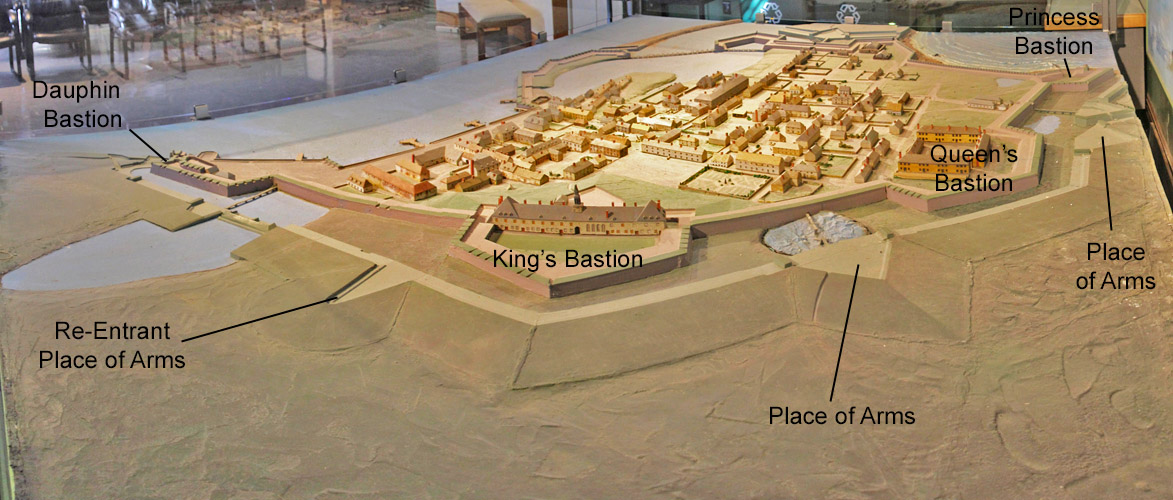

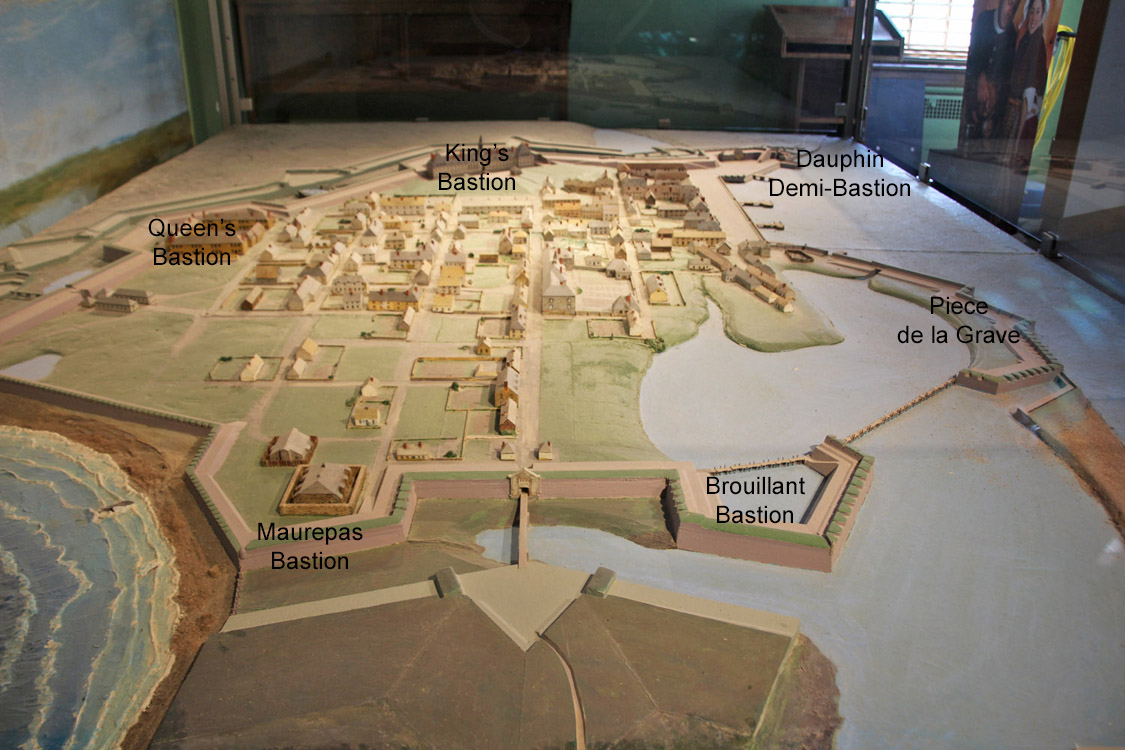

This model reflects the cavalier added to the Dauphin Bastion after the 1745 siege.

A large pond in front of the Dauphin Demi-Bastion aided the defenses of this sector.

In 1758, British siege lines got to within about 50 yards of the

Dauphin Bastion. On July 9th, the French launched a sortie from

this gate, capturing

some of the British earthworks before returning to the fortress.

Because of the stresses caused by freezing and thawing, the walls

deteriorated quickly. To help protect them, wooden planking covered

some walls.

Dauphin Gate

Guard houses on either side of the gate have firing ports.

Inside the Dauphin Demi-Bastion

The Dauphin Demi-Bastion was built between 1728 and 1730, and it is

reconstructed to its 1745 appearance. At this point in time the

bastion was arranged so that artillery was facing the harbor, creating

a crossfire with the Grand Battery. The bastion's flank had

cannon covering the curtain extending to the King's Bastion, but there

were no

cannon facing directly inland. This was a major

deficiency in the 1745 siege - this was alieviated by the time of the

second siege by an elevated cavalier. Despite this, in the

1758 siege the cavalier and the bastion were bombarded into ruins.

Among those "manning" the guns was Madame Drucourt, wife of the

governor, who was known to fire the cannon.

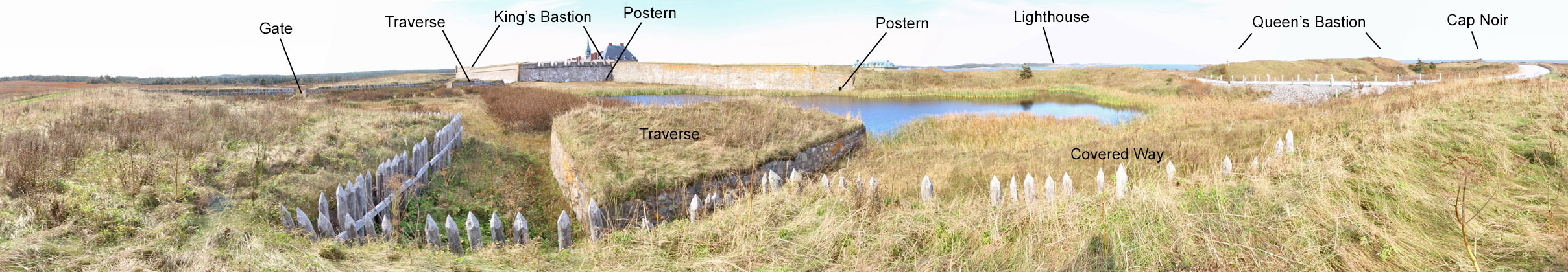

From Dauphin to King's Bastions

In the 1758 siege, the curtain between these two bastions was breached,

making an assault feasible. Rather than face the horrors of

street fighting, the French surrendered. Although the British

artillery was well respected, at least one historian has remarked on

the deficiencies of the British engineers.

Cannon on the flank of the Dauphin bastion swept the curtain extending to the King's Bastion.

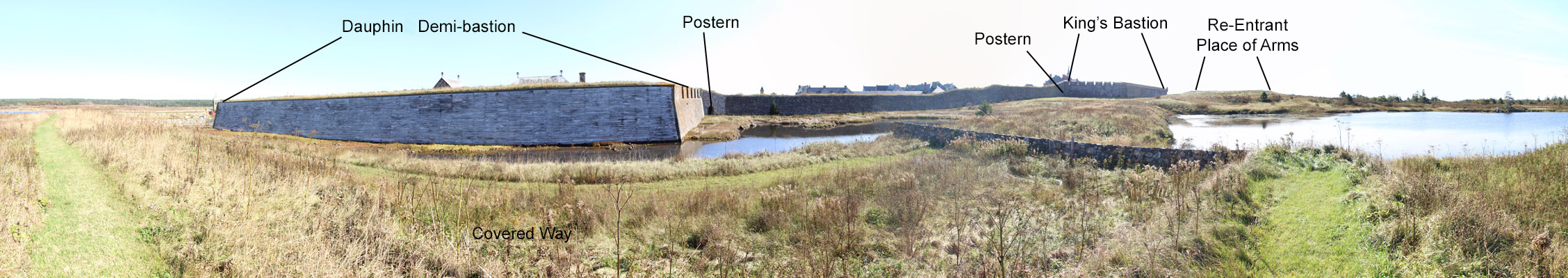

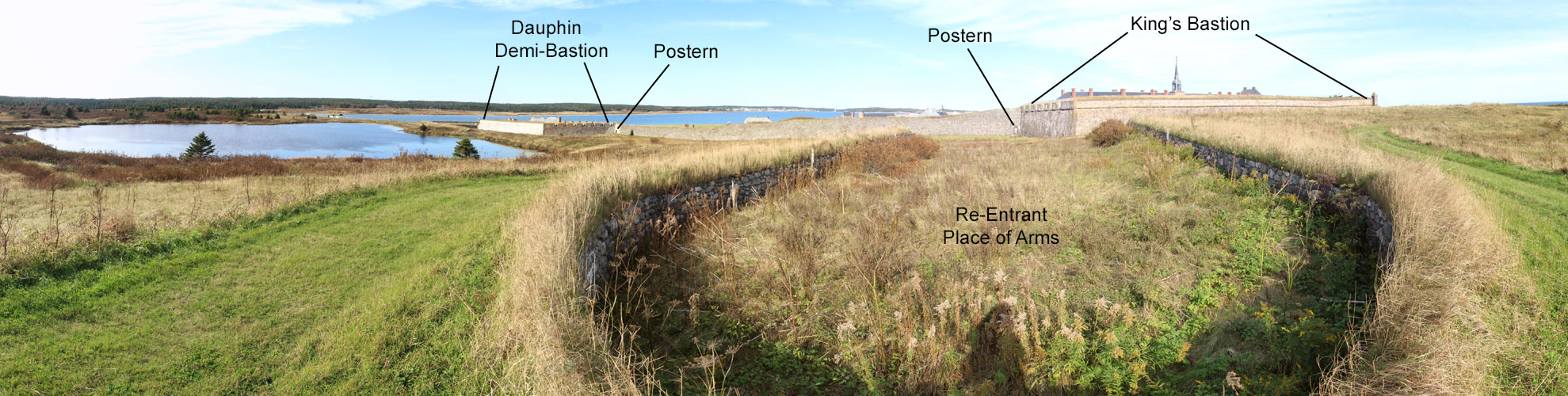

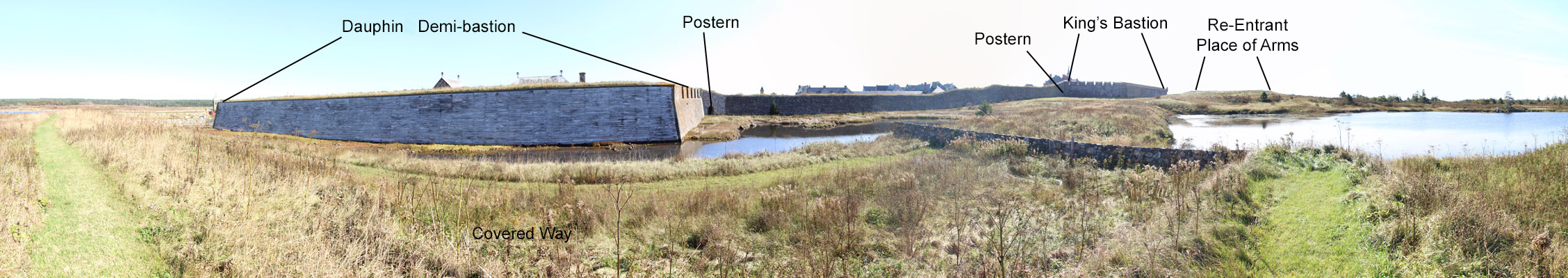

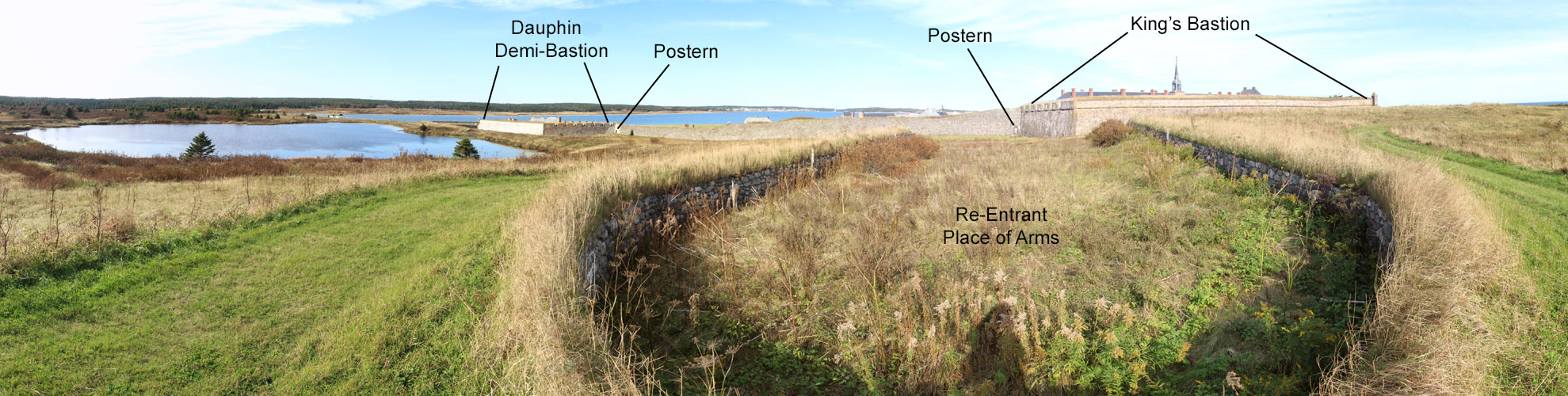

Re-Entrant Place of Arms

Although the King's Bastion was on high ground, dead ground existed to

its front, ground that could not be covered by fire from the fortress.

The answer was to build a re-entrant place of arms to the front

of the bastion.

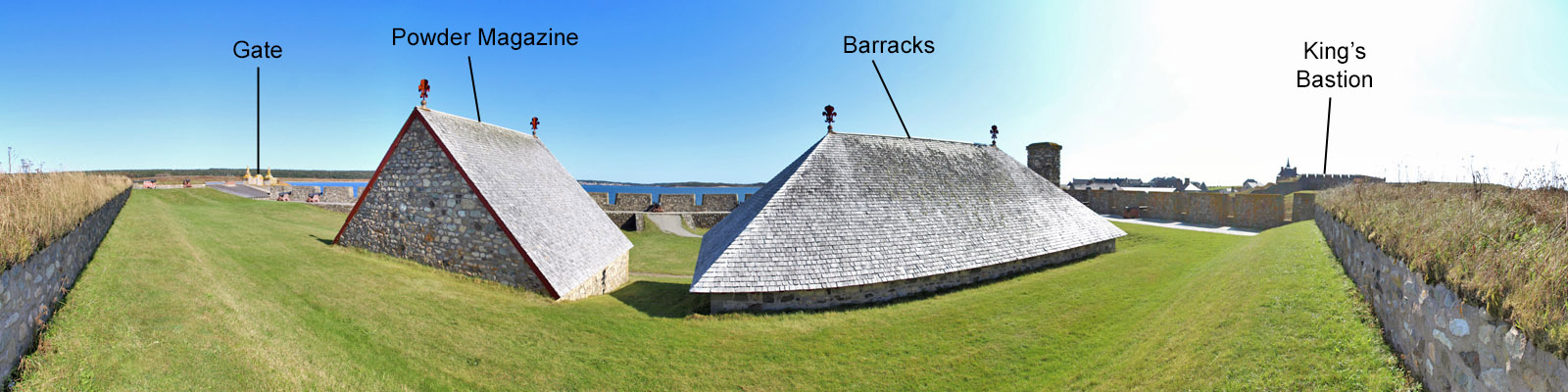

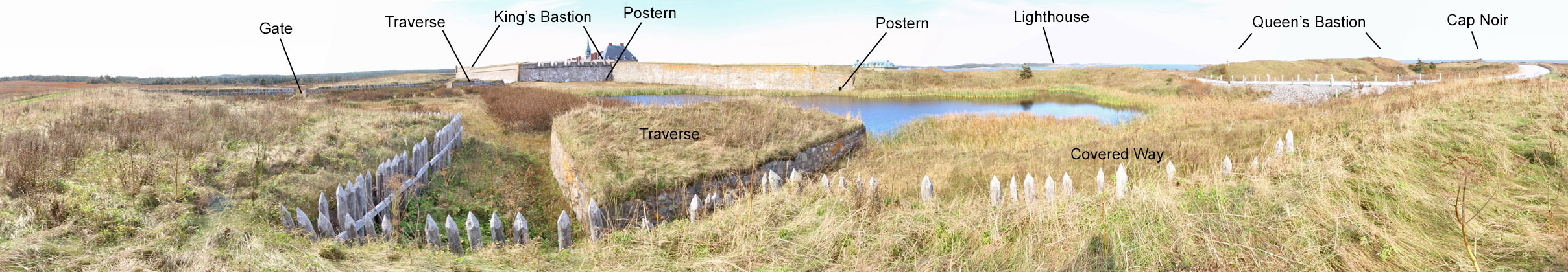

King's Bastion

Like the Dauphin Demi-Bastion, cannon in the King's Bastion were

generally aligned the sweep the area between bastions and to the front

of other bastions. The fort

designers believed that the rough ground and marshes around the

fort made a formal siege unlikely. Indeed, swampy ground made the

transport of cannon from the landing site to siege lines a difficult

task. The ground was shaped by glaciers, leaving an odd array of

small hills and ponds in front of the fortress.

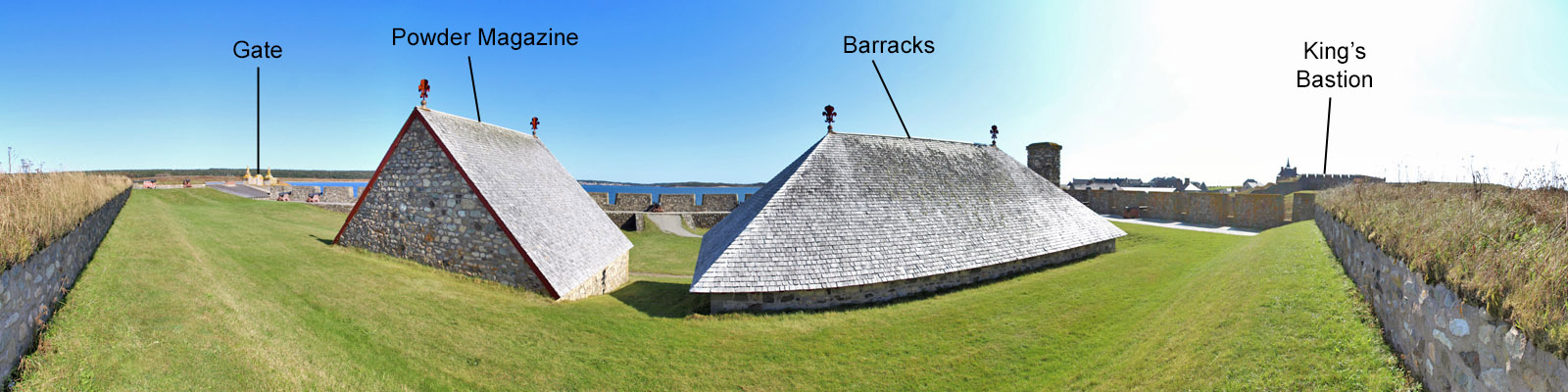

The longest building in North

America is at the base of the bastion, the gorge - this building contained a

barracks, a chapel, and facilities for the governor.

A sentry box overlooks the whole area in front of the fortress.

You can see that high ground overlooks the fortress. Not

visible in the photo, a countermine gallery extended toward enemy siege

lines from the ditch below.

Southeastern End of Building

Here you can see the ditch to the rear of the building followed by a covered way for defense by infantry.

Governor's Areas

Chapel

Barracks

Rear of the Building

The area here could be defended by infantry from an attack on the rear of

the bastion. A traverse at left protected from flanking fire.

Place of Arms

The fortiffication of the rear of the King's Bastion was fortified made it a sort of poor man's citadel.

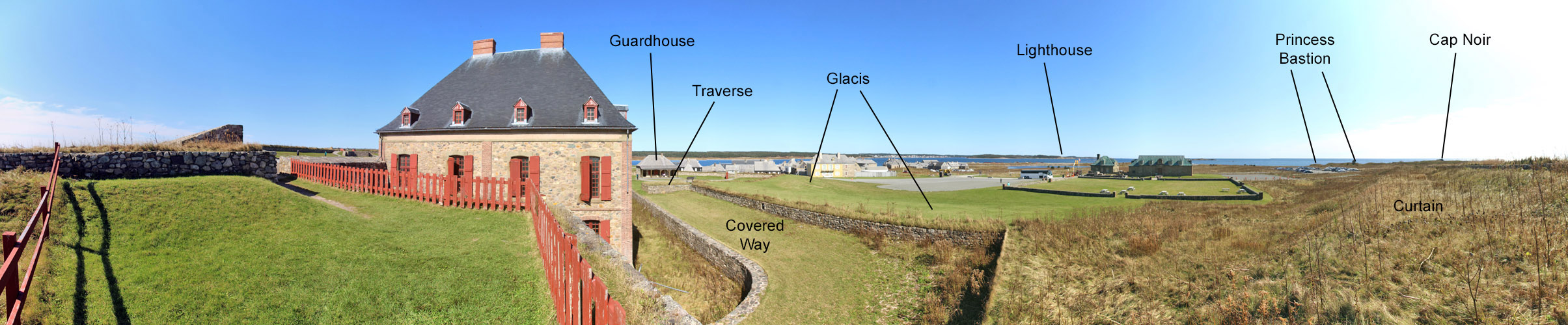

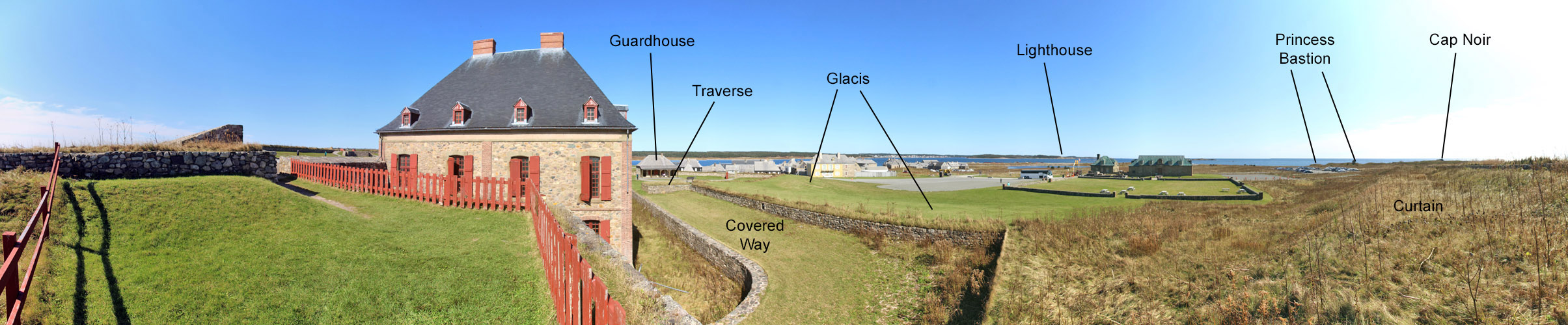

Here you can see the glacis, or cleared field of fire, at the rear of the King's Bastion.

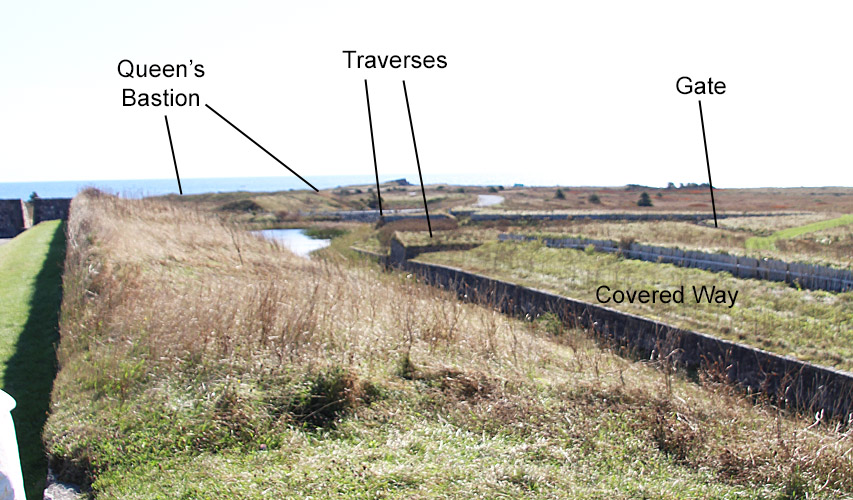

Place of Arms From King's Bastion

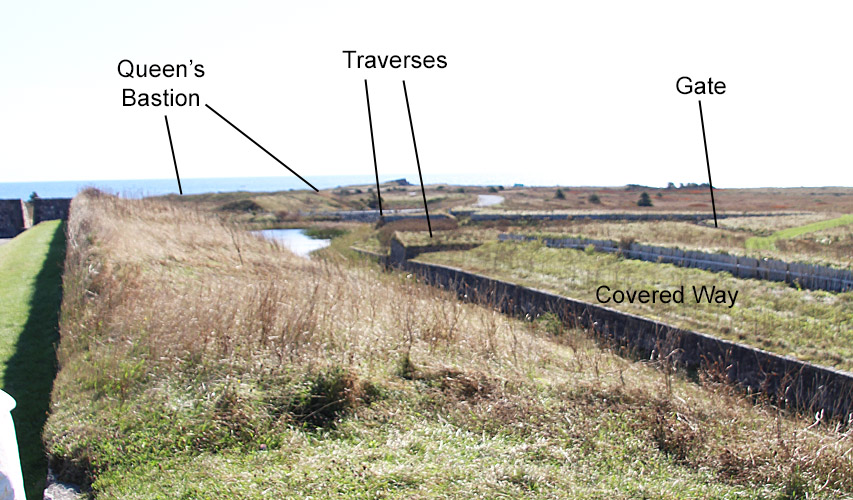

Infantry manned defenses to the front of the main walls, the covered way and outworks like places of arms.

An inverted V-shaped outwork, a place of

arms, can be seen from the ramparts. Traverses on each end of it

protected from flanking fire and allowed a continued defense if the

covered way was captured.

Place of Arms from Other Side

Here you can see the traverses at either flank of the place of arms.

The reconstruction ends between the King's and Queen's Bastions.

After the 1745 siege, the New Englanders built a wooden barracks

inside the Queen's Bastion.

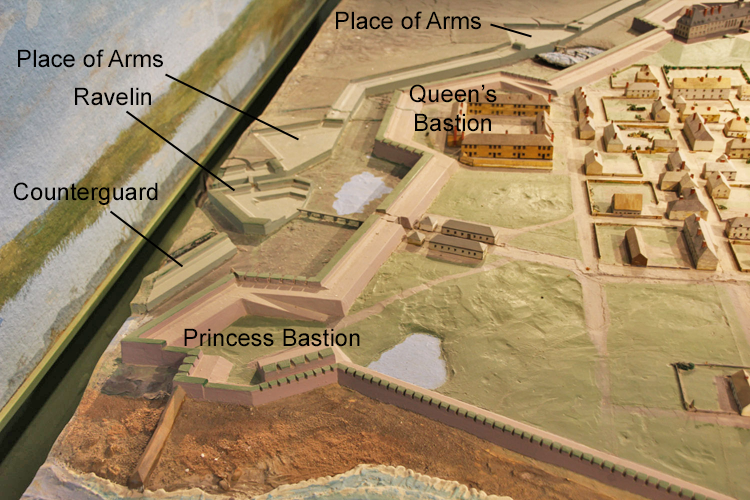

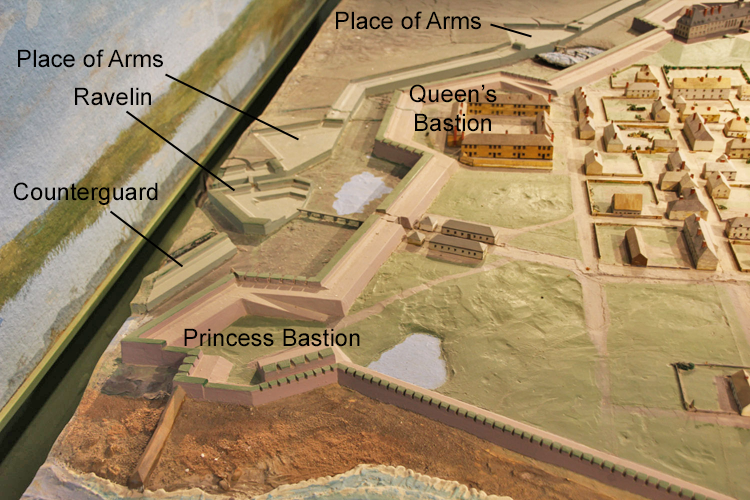

From Princess Bastion

In 1731, construction began on the Queen's and Princess Bastions.

Not reconstructed, it is difficult to make sense of the

fortifications here. A counterguard gave added protection to the

Princess bastion. A ravelin was built between the Queen's and

Princess Bastions as well as a place of arms - both are difficult to make out from the ruins.

In 1737, construction began on the Maurepas and Brouillant Bastions and the Piece de la Grave, which faced the harbor.

Bakery

Frederic Gate

Government buildings were topped by symbols of the monarchy.

Copyright 2020 by John Hamill