|

|

| Traub | BG Lucien Berry |

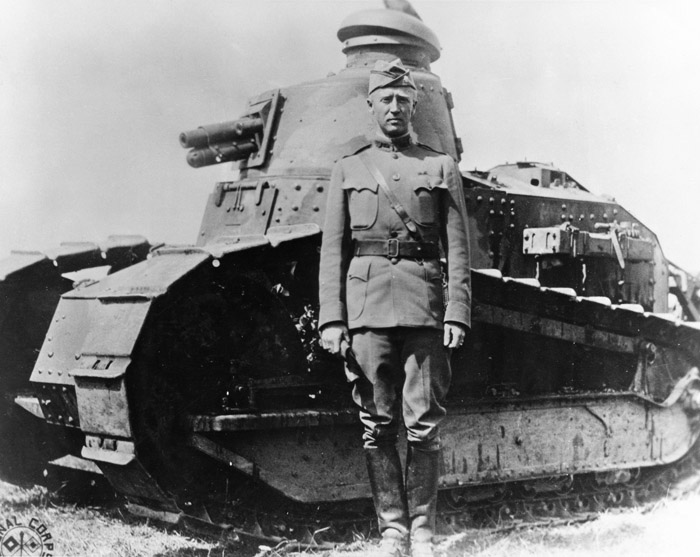

Maj Serano Brett - One of the few tank officers to stay in tanks after the war, he stayed in armor WWII. |

The preliminary bombardment and the barrage that followed accounted for

most of the over 40,000 rounds that the divisional artillery fired that

day. The attack began in the early morning fog at 5:30 with the

men having had no breakfast. The division attacked with the

69th Brigade under Col Louis Nuttman in front -with Hamilton's 137th

Regiment on the left and Howland's 138th on the right. Each

regiment was deployed in column of battalions. The fog was such

that liason between units was difficult and aviators could not see the

line because of a "solid white snow-bank of clouds."

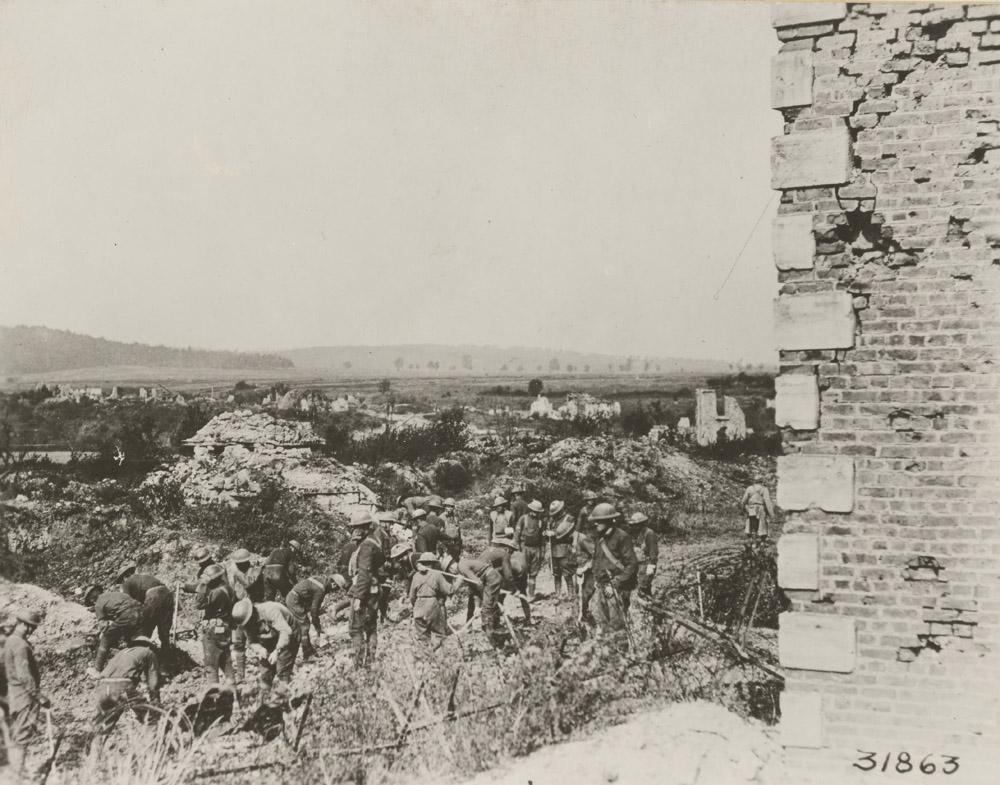

Communication by runners broke down as the men were either

wounded or got lost. The Americans soon made their way through the German front line - note that the Germans used a reverse slope position. The area was one of the few open ones suitable for tanks, albiet a narrow one of a mile and a half separated by the Aire River, so George Patton's 1st Tank Brigade was tasked with supporting the attacks of the 28th and 35th Divisions. The 28th Division front could accomodate only a single company (B/344th), but the 35th could take two tank companies. The 35th Division was supported by Companies A and C of the 344th Tank Bn under Maj Serano Brett just to the rear of the front line infantry. The 344th had 69 Renault FTs. A mile to the rear was Cpt Ranulf Compton's 345th Tank Bn with 58 Renault FTs, with B and C Companies supporting 35th Division and A Company supporting the 28th Division. Another mile back was the reserve, two groupes of a total of 28 heavy Schneider tanks under French Maj. Chanoine. Patton was not yet present, but his tanks advanced through the German frontline defenses and continued the advance toward Cheppy. Although the German frontline was taken without much difficulty, the main German defense would be made further to the rear near Cheppy. |

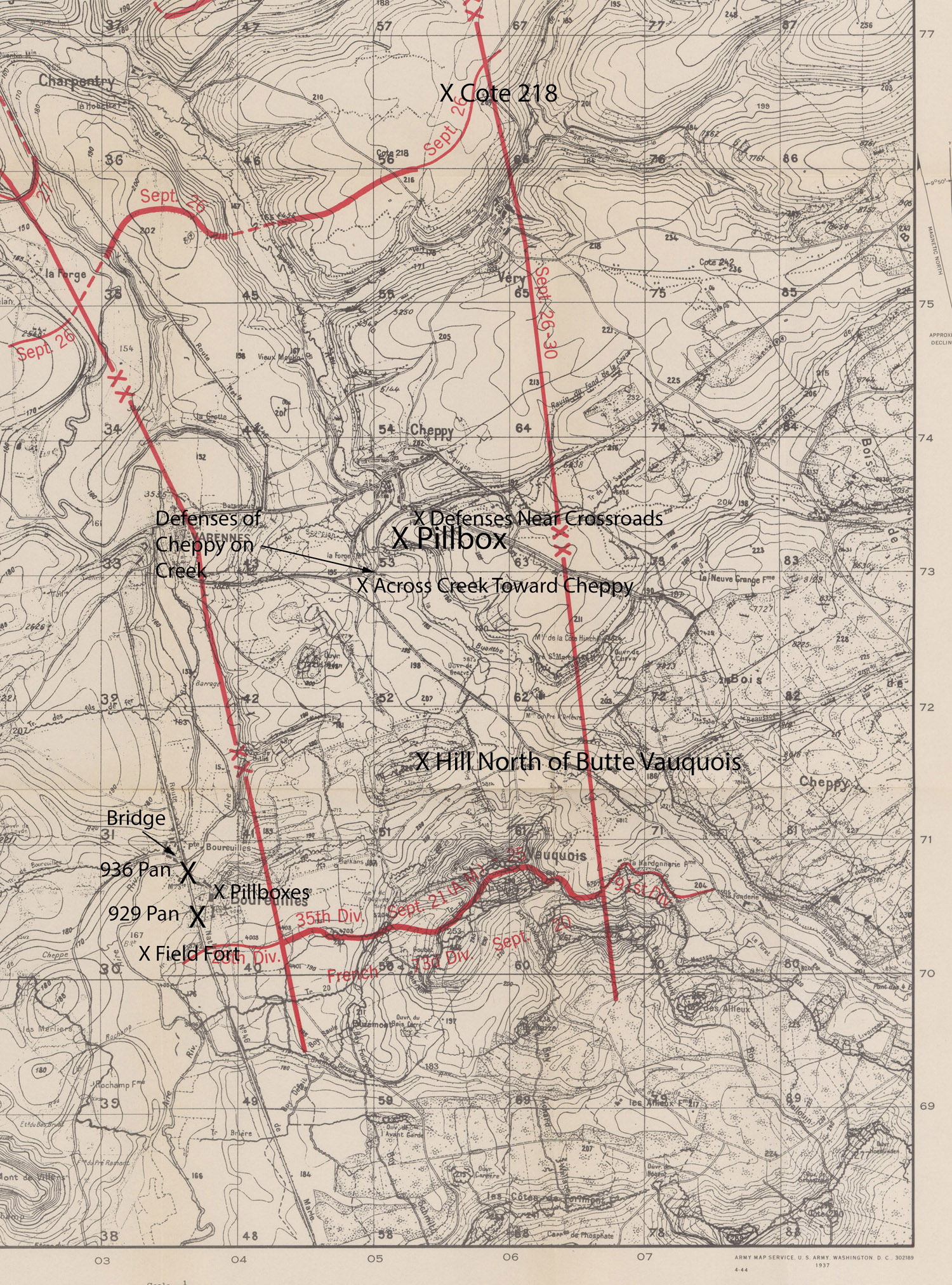

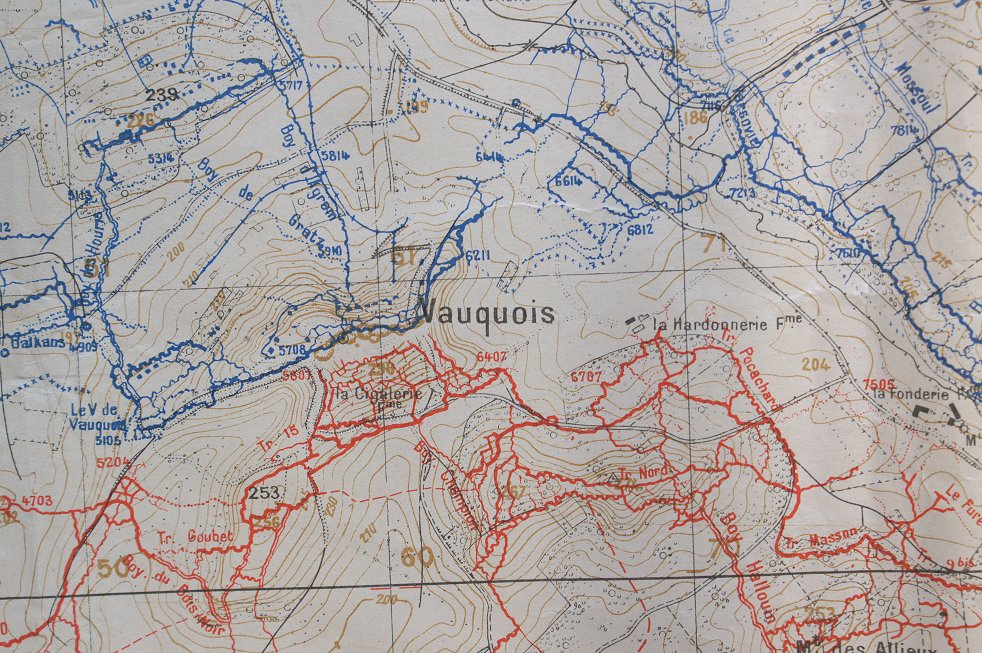

| The scene of stagnant mine

warfare that had blown the top off a hill,

creating two ridges, Butte Vauquois was one of the difficult areas in

the American attack sector, and it dominated the land below it.

The Americans of the 35th Division abandoned the trenches

here on the hilltop five hours before the attack. The bombardment

of the hill was intense. When it lifted, two American

companies of the 139th Regiment advanced immediately behind the

barrage, killing and

capturing the Germans as they emerged from their bunkers.

Only 75 men and six machine guns defended the Butte, and

they soon surrendered. Meanwhile, Americans on either side of the

butte penetrated the

German line. |

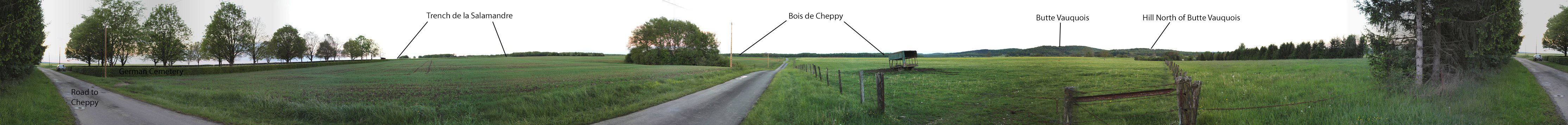

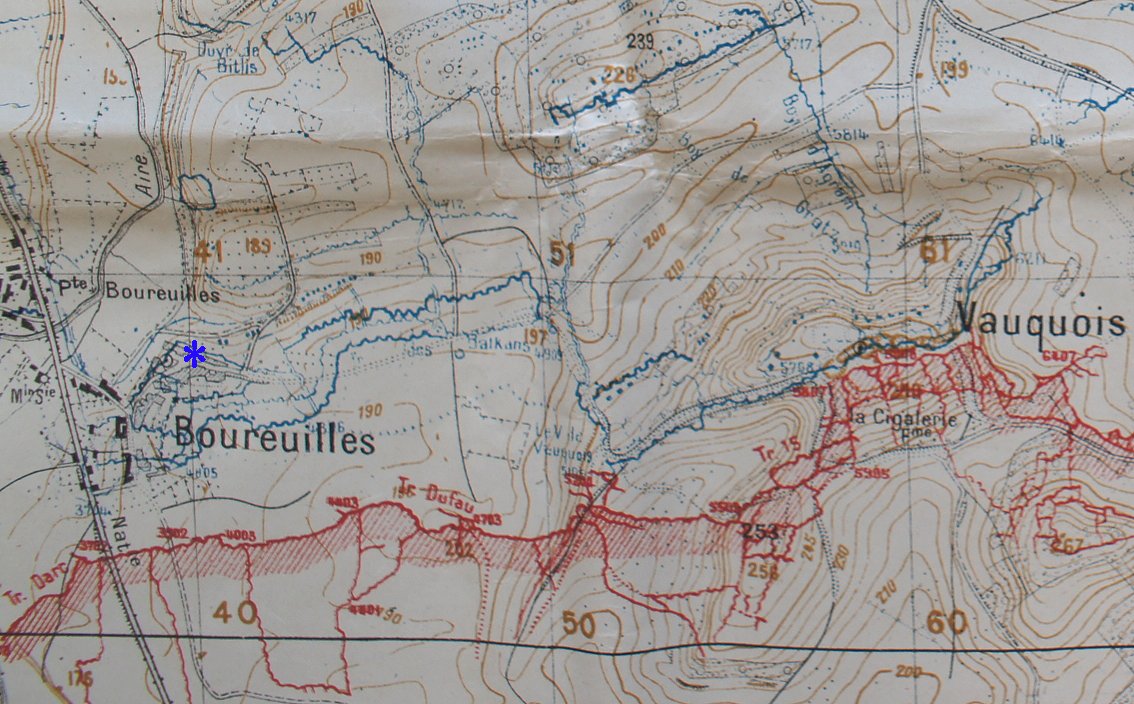

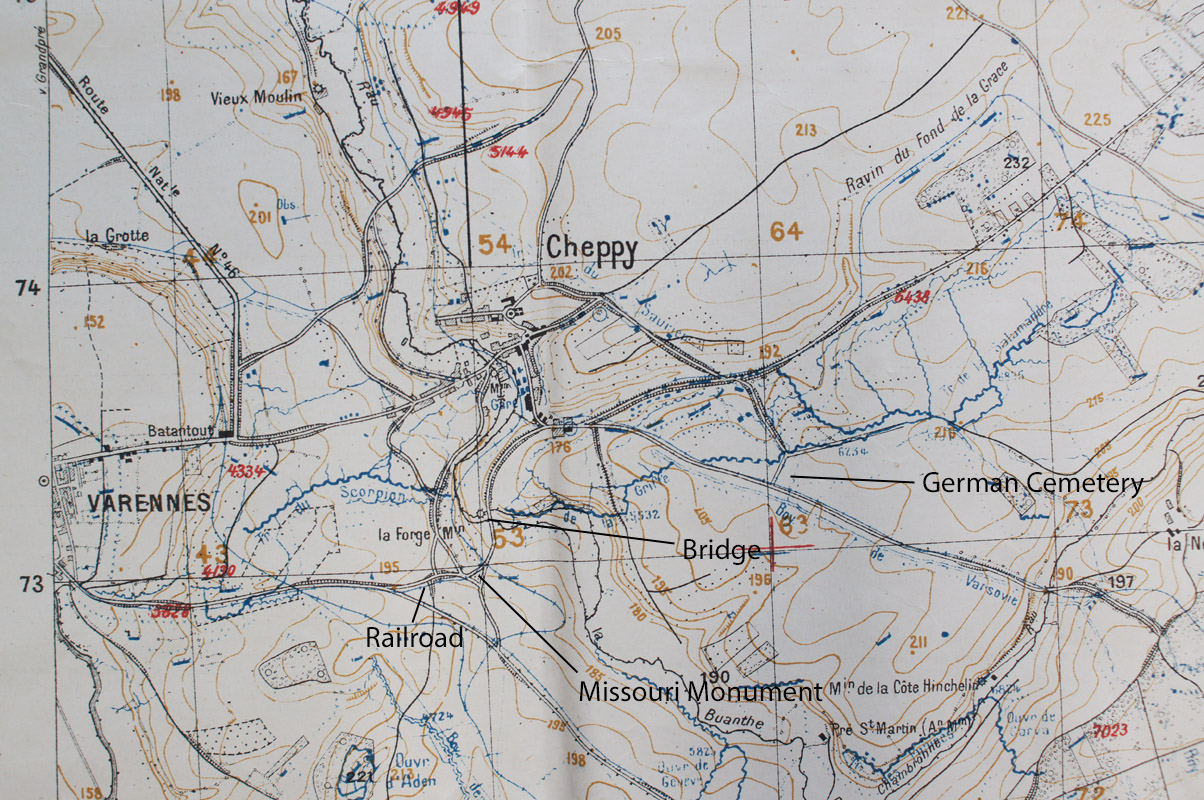

1918 Trench Map From George C. Marshall Library |

| The troops had arrived at about 8:30 and encountered strong German defenses behind the Baunthe. A confused action ensued. Company M advanced straight into Cheppy, through the fog and past enemy pillboxes that they believed were unoccupied - occupied they were, but the Germans, unable to tell whose troops they were, let them pass. Company M passed straight through the town, collecting prisoners as they went, with Col Howland following, then Company L. Returning from whence they came, the Americans were fired on by the Germans, and the prisoners ran for it. Meanwhile, Company I entered the action. Private Nels Wold, a man of Scandanavian descent, was a member of Company I, 138th Infantry, specifically the leftmost platoon of the battalion, which was to provide a communication link with the 137th Regiment to the left. The 48 man platoon lost contact with both its own battalion and with the neighboring regiment - encountering and joining about a dozen scouts under a Lt Wingate at 11am, the group infiltrated behind German lines. The fog lifted as the group was concealed in a clump of trees on a hillside. When a German machine gun opened fire from some nearby bushes, the group sprang into action, taking out German machinegun nests. One of them in some bushes was too strongly placed, so Wold volunteered to approach it alone and attack it from the rear. This he did, killing two and capturing three. The group continued and Wold tried four more times, but he was killed in his fifth attempt as he negotiated the camoflauge screen. Wold was awarded the Medal of Honor. The group continued to advance, attacking a group of Germans, killing half of them and pursuing the rest. This pursuit ended up in Varennes , in 28th Division territory. In all the group took 60 prisoners that day. |  Nels Wold |

Cpt Skinner |

The fog lifting at about 10:00 changed the battle.

Captain Alexander Skinner in command of three platoons of I

Company was facing the road, then the bridge over the Baunthe.

"Unwilling to sacrifice his men when his company was held up by

terrific machinegun fire from iron pill boxes in the Hindenburg Line,"

Captain Alexander Skinker with a two man Chauchat automatic rifle team

attacked

a German machine gun nest, not knowing that it was steel or concrete.

The ammunition carrier was killed, and

Skinker took over until he was also killed, then the third man.

Skinker's body, and that of one

of his men, was buried beside the road. He was awarded the Medal

of Honor. Col Howland, the new commander of 138th Regiment, had

his command post about three hundred yards to the rear of where Skinner

was killed - many in headquarters had been killed or wounded.

Howland encountered two Renault FTs -they were thought to

be manned by the French. French speaking veteran of the French

army Sgt Morel got out of a ditch and ran to the tanks. Opening

the trap door, the tanker shocked Morel by asking, in perfect

English, "Well, what the hell do YOU want?" He directed them

to attack. Advancing, they encountered heavy fire and turned back

- on orders of Howland who feared the German artillery that the tanks

attracted. A French lieutenant was in charge of the tanks, and he

told Howland that eight more big ones were on the way. Howland

sent the Frenchman to rush them on and was soon wounded in the hand.

|

Col Harry S Howland |

Patton's story presented below is based on his letters and an interview from his aide. By the time Patton arrived, Renault FT tanks of Company B, 345th Tank Bn had tried to cross the Baunthe River, with those that had crossed got stuck in a German trench. Two heavy French made tanks also became immobilized. Patton rallied some infantry in a light rail cut. He later wrote to his wife,"...We hollared at them and called them all sorts of names so they stayed, but they were scared and some acted badly, some put on gas masks, some covered their face with their hands but none did a damned thing to kill Bosch. There were no officers there but me." Joe Angelo was apparently a little behind the colonel. In an interview he told his story, "I was walking by the side of the Colonel, but when we came to a crossroad the Colonel told me to remain there and be on the watch for Germans. While I was on duty two American Doughboys came along. I asked them what what [sic–their] mission was they replied that they were 'just mopping up.' 'Well,' I said, 'if you don't get out of here you will get mopped up, as the Germans are pouring plenty of lead our way.' When several high explosive shells burst the Doughboys took refuge in a shack. A moment later a shell hit the shack. The Doughboys were blown to atoms. A moment later I saw two German machine gunners from behind a bush and they fired on me. I returned the fire and killed one; the other one beat it. The Colonel, who was ahead of me, appeared on top of a knoll and shouted: 'Joe, is that you shooting down there?' Then I thought sure hell had broken loose. Bullets from machine guns just naturally rained all around. 'Come on, we'll clean out these nests,' shouted the Colonel, and I followed him up the hill." The effort failed, however, and the men continued to fall back, with Patton apparently following. There, 100 yards behind the intersection, he found tanks, stuck in craters and trenches - he ordered the tank crews to dig out their tanks. "To hell with them. They can't hit me.", he is reported to have said. At least one man wasn't working to Patton's satisfaction, "I think I killed one man here - he would not work so I hit him over the head with a shovel. Angelo said, "The Colonel ordered me to follow him and when he reached the tanks, almost hub deep in the mud, he grabbed a shovel and began digging the tanks free. Other men and I also got busy digging. The Germans were sending across a heavy artillery fire, but finally we got the tanks moving and took them over the hill." With the tanks now unstuck, Patton led five tanks and around 150 infantry in an attack to the northwest to take German machine gun nests along the northerly Varennes-Cheppy Road. Angelo said, "The Colonel here found some infantrymen who did not know what to do, as their officers had been killed. The Colonel instructed me to place them with the tank detachment. Later the Colonel told me to get around to the side and wipe out the machine gun nests. 'Take fifteen men with you,' he ordered. 'I'm sorry,' I told him, 'but they have all been killed.' 'My God! They are not all gone?' the Colonel cried. When I told him the infantrymen had been killed by machine guns he ordered me to accompany him, declaring he would clear them out. I thought the Colonel had gone mad, and grabbed him. He grabbed me by the hair and shook me to my senses. Then I followed him." Encountering heavy fire, the men went to ground. Fearing for his life and wanting to run to the rear, Patton remembered all of his reincarnated lives and his grandfather at Cedar Creek and went forward once again, this time with just six men, four of whom were soon hit. Accoeding to Angelo, "We went about thirty yards and the Colonel fell with a bullet in his thigh." Patton was hit from a range of about 50 meters in the upper thigh and buttocks, but he continued for 40 feet until he collapsed in shock. Private Angelo dragged him to a shell hole - "I assisted the Colonel into a shellhole, bandaged his wounds and took observations of our surroundings[.] Shells flew all about us. Two hours later the Colonel revived and ordered me to go to Major [Sereno] Brett and instruct him to assume command of the tank corps [sic—304th Brigade]. I found him and did so. Then [I] reported back to the Colonel. A few moments later the Colonel, with three tanks, one French and two American, camped about twenty yards from the shellhole. 'Jump out there,' the Colonel ordered, 'and scatter those tanks or they will be blown up.' I rushed out, gave the order and came back again. The American tanks got away, but the French tank was shot to pieces and the men killed. The colonel then ordered me to get out on top of our shellhole and prevent any oncoming tanks from getting below us, the fire from the enemy being terribly heavy. Then the Colonel said, 'Joe, the Germans have been making this shell hole a living hell since you left. Get a tank and wipe out those nests.' This was done and after that I found four infantrymen who carried the Colonel to the rear" Patton was evacuated to the Neuvilly church. Both Patton and Angelo were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross but Patton immodestly felt that he deserved the Medal of Honor. |

Lt Col George Patton |

Joseph Angelo |

Patton described Angelo as "without doubt the bravest man in the

American Army. I have never seen his equal." In 1932 Angelo

became involved in the Bonus Army in Washington DC, veterans

organization that was crushed by a force commanded in part by Patton.

Angelo met with Patton, but Patton said, "I do not know this

man. Take him away and under no circumstances permit him to return." He

explained to his fellow officers that Angelo had "dragged me from a

shell hole under fire. I got him a decoration for it. Since the war, my

mother and I have more than supported him. We have given him money. We

have set him up in business several times. Can you imagine the

headlines if the papers got word of our meeting here this morning. Of

course, we'll take care of him anyway." In a letter to his father, Patton wrote of the battle, "..if I had not thought of you and Mom + B and my ancestors I would never have charged. That is I would not have started for it is hell to go into rifle fire so heavy that one fancies the air is thick like molasses with it, After I got going it was easy but the start is like a cold bath... Maj. Brett who has been in all the while says that was the heaviest fire of the whole battle. They were 12 M.G. rifle in front of me at about 150 yds. Bashed by a battalion of guard infantry. Which while from fifty to 150 machine guns and firing at us from the flanks. My “guardian spirits” must have had a job to keep me from getting killed so we can’t blame them for letting me slip by and hit me in the leg... You know I have always feared I was a coward at heart but I am beginning to doubt it. Our education is at fault in picturing death as such a terrible thing it is nothing and very easy to get. That does not mean that I hunt for it but the fear of it does not – at least has not deterred me from doing what approved my duty." |

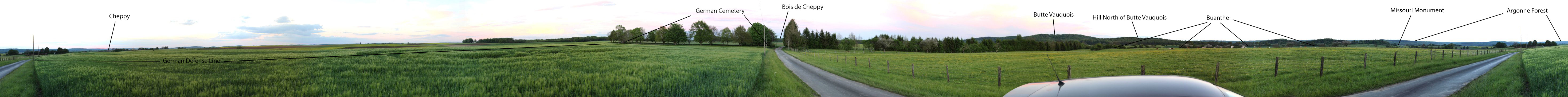

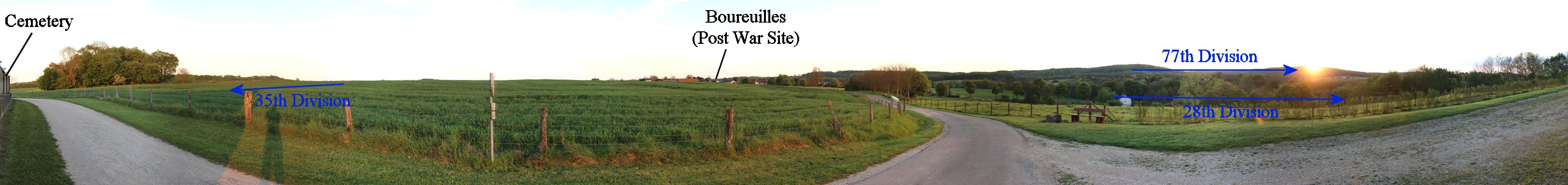

| The view is to the east in the direction of Cheppy.

The road at

right is likely the more southerly of two Varennes-Cheppy roads - the

road

which at present goes to the Missouri Memorial and the site of Patton's

attack. This sector was the responsibility of Lt Col Clad

Hamilton's 137th Regiment. Like elsewhere on the 35th Division

front, artillery was still far to the rear in a traffic jam on the

Route Nationale, and infantry alone wasn't able to make much progress.

Hamilton was found in a shell hole having suffered a nervous

breakdown - the regiment was in chaos that morning. Col Carl

Ristine of the 139th Regiment, finding the demoralized Hamilton unable

and unwilling to advance and unable to contact higher headquarters,

took the initiative and moved his regiment to the front ahead of the

137th. For this decision he would receive heavy criticism

- his action further disorganized the 137th to the point

of disintegration, but as fortune would have it, the timing for an

attack was good as the 28th Division, having been halted before

Varennes, got the support of six tank companies and captured Varennes

in the early afternoon. Had Varennes not been taken by this

point, enfilade fire from the town might have smashed both the 137th

and 139th Regiments. The now confused 139th continued the advance

to Hill 202, but because of communication problems, they did not

receive orders to continue further. Despite the criticism of

Ristine, his actions allowed the 35th Division to make good progress,

putting them ahead of the divisions on each flank - historian Robert

Ferrell suggests that the root of most of the criticism of Ristine is bias by

Regulars against the National Guard. The 35th Division was now in bad shape, with two of its four regiments having taken heavy losses and sustained command problems, a third regiment confused from passing through another, and a fourth regiment the only one remaining in good shape. Traub, the division commander, was out of touch with subordinates. |

Col. Carl Ristine |