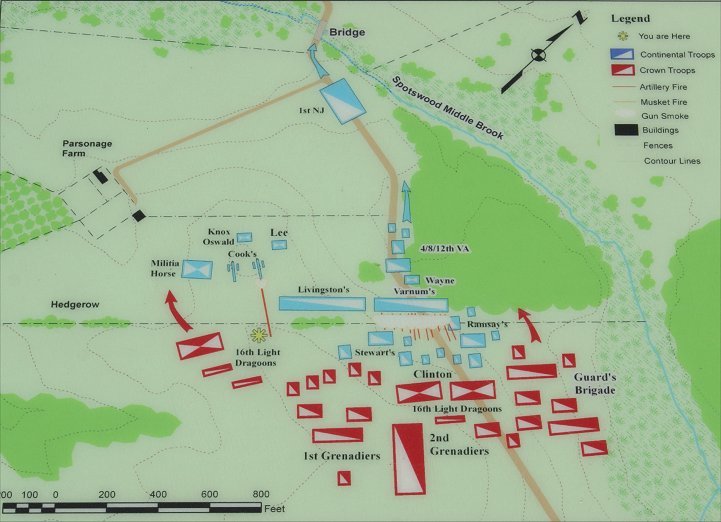

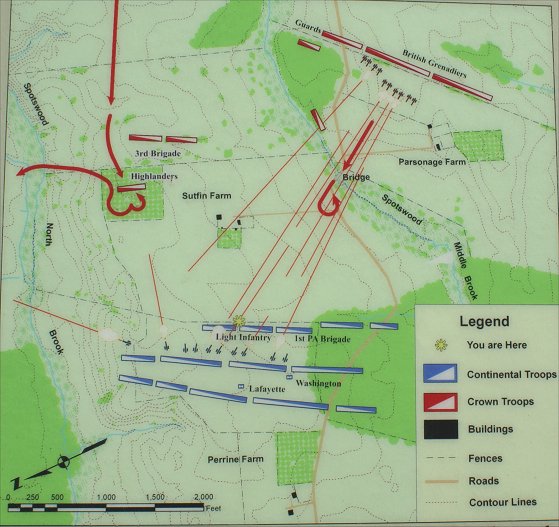

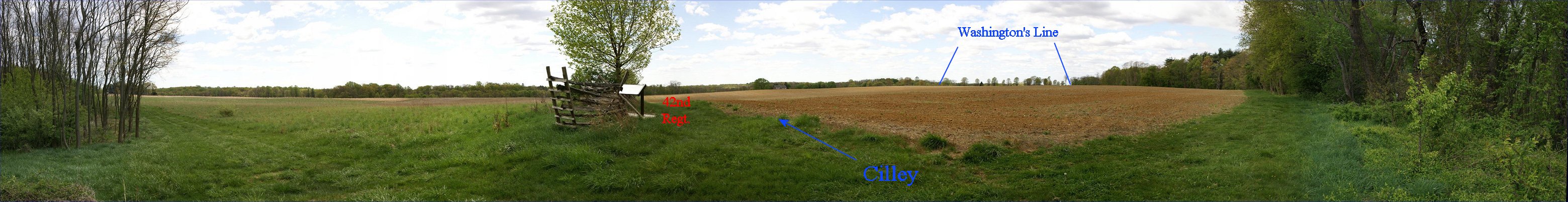

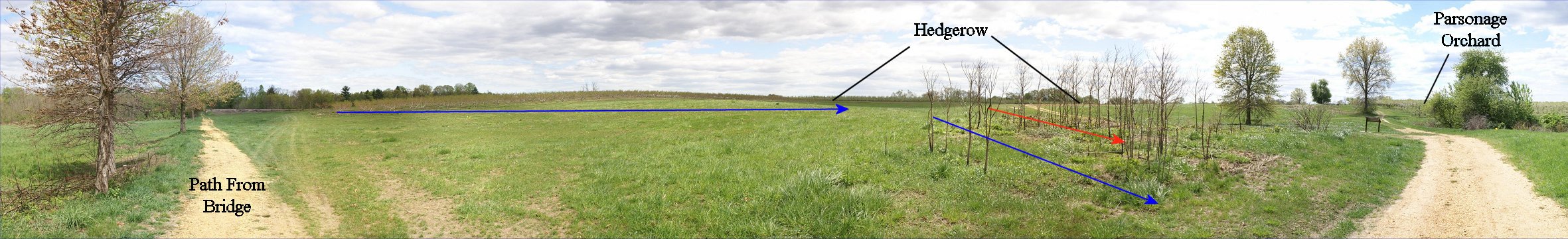

Washington ordered Anthony Wayne with a group of picked men ahead and into the woods on the right side of the panorama to delay the British, then he returned to the main body to organize a line of battle. As the British crossed the Middle Morass and proceeded forward, American artillery near where the photo was taken fired solid shot and canister into them. Wayne's men ambushed the Guards and Grenadiers and the 16th Light Dragoons as they passed, and the British responded with an immediate attack. In hand to hand fighting, Wayne's men were forced back, and the artillery was withdrawn in the face of the advancing British. The British had paid dearly for this victory, and the troops were not in good order.