Mulberry Harbor - Arromanches

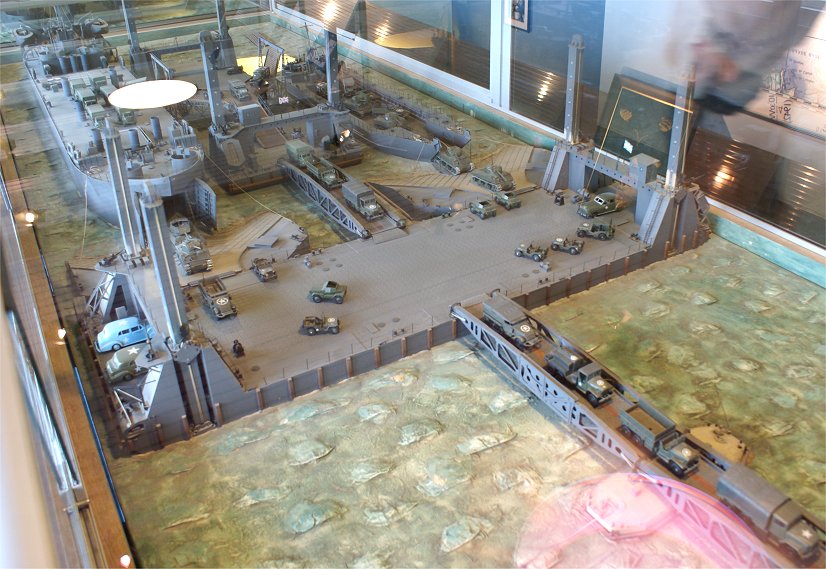

To supplement supply from landing craft on the beach, the British

invented and built a pre-fabricated harbor, which they towed into place

and assembled on the coast of France. Two harbors were actually

made, one at Arromanches for the British and another on Omaha Beach for

the Americans. A storm largely destroyed the Omaha Beach harbor,

but the one at Arromanches was repaired and continued to function into the autumn of

1944, even after a number of ports had been captured. Remains of

the harbor are still visible, and there is a wonderful museum the town

of Arromanches explaining it.

Design was begun in 1942 in reaction to the Dieppe Raid, when it became

apparent that the Germans would keep French ports well defended.

In addition, in the Mediterranean the Germans showed their

willingness and

skill at destroying ports before their capture. Winston Churchill

was an eager proponent of the Mulberry Harbor concept. Despite

Churchill's enthusiasm, final construction of the pre-fabricated

components was a rush job in the spring of 1944. Assembly in

Normandy began just a few days after D-Day.

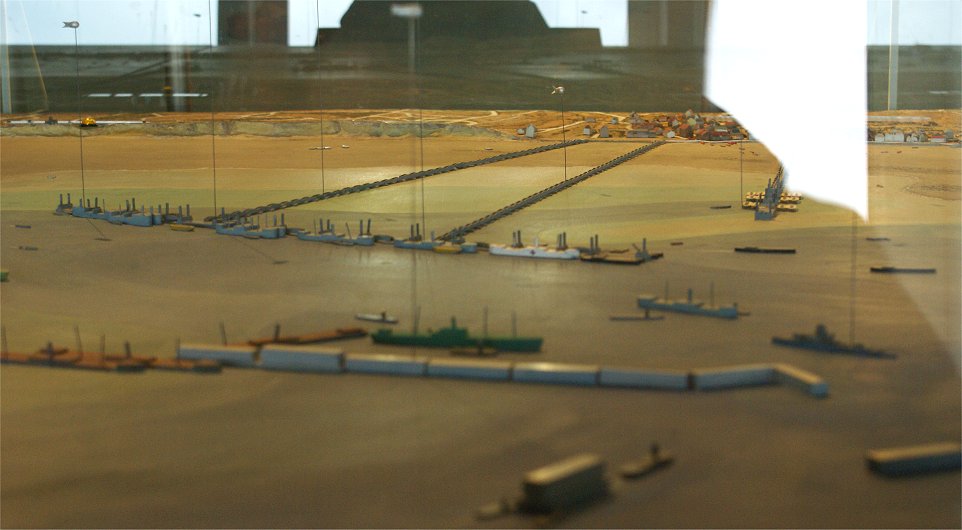

Mulberry from Longues Battery

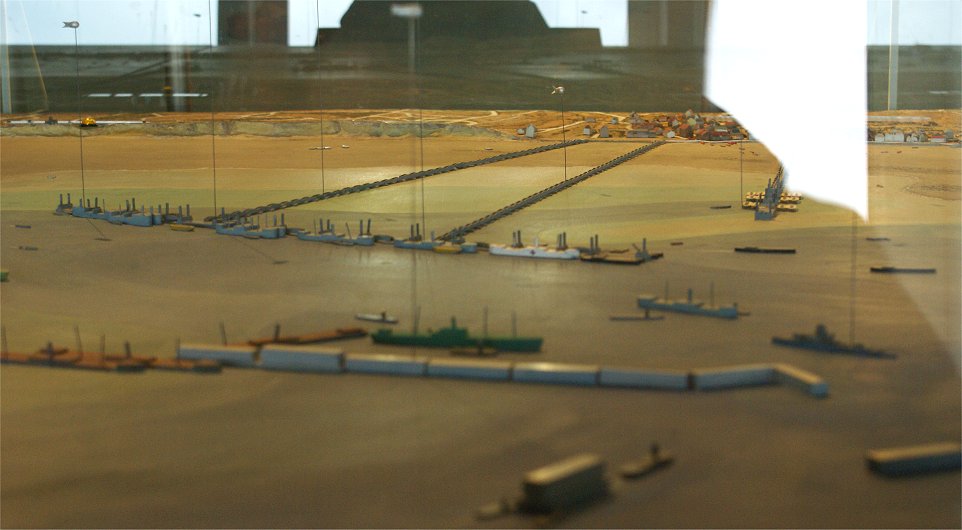

From Atop the cliffs to the west, you can make out the shape of the

artificial port. A rectangular shaped area was protected by

blockships and pre-fabricated caissons.

This is the view from just outside the museum. In the distance,

you can see the remains of the caissons that protected the harbor.

On the beach, you can see the remains of the floats of the

pontoon bridges, which came ashore in this vicinity.

Behind the protection of these breakwaters (foreground), bridges on

pontoon bridges were built out to piers where ships could be offloaded

(center and background).

Caissons

These are the large concrete structures floated, towed

really, across the Channel, then flooded so they would sink and

form a barrier to high waves. Unfortunately they were designed

only for flooding, not for being pumped out, so they were immovable

once sunk. They were also liable to being swamped, so later

version had a steel top despite the wartime shortage of steel.

Some of the caissons mounted anti-aircraft guns or barrage

ballons. Although the Luftwaffe had sustained heavy losses by

this point in the war, the Mulberry Harbor was an inviting target.

In

addition to here at Arromanches, casissons and

blockships were used elsewhere to ease debarkment across beaches

without the system of bridges and piers. Floating devices

known as bombardons were also placed further out than the caissons in

the hope of protecting the harbor, but they were generally considered

to be a failure.

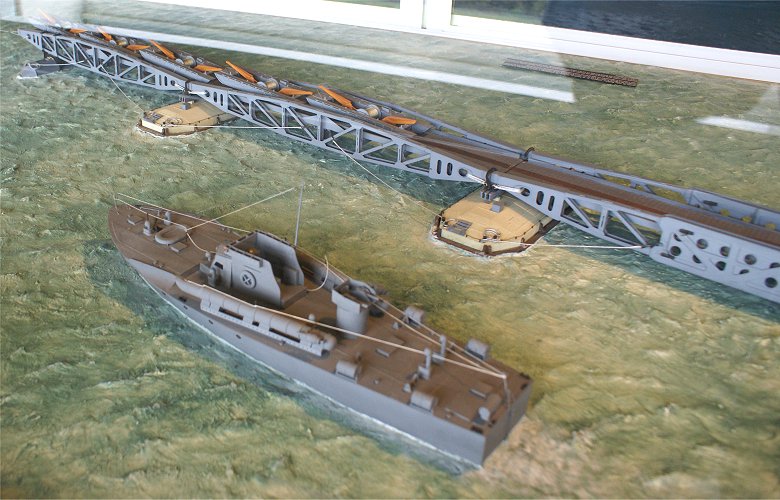

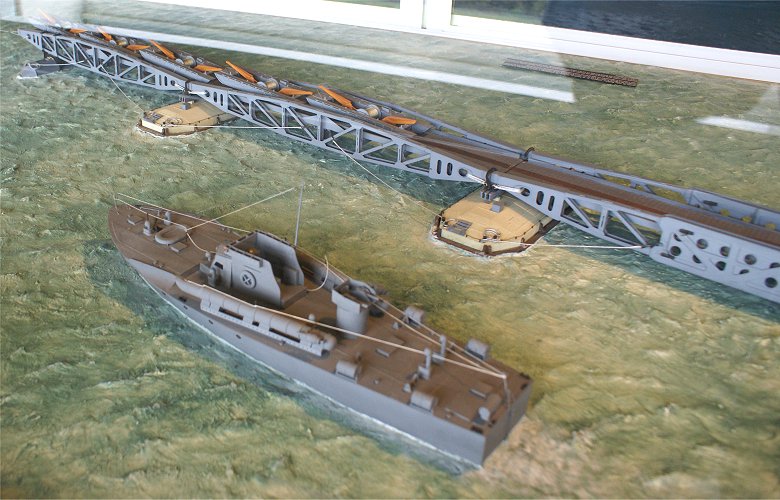

Also towed across the Channel were the bridges and pontoons. Maximum towing speed was just three knots.

The pontoons were anchored, stongly at Arromanches, not so strongly at

Omaha Beach. The bridging sections were designed to be flexible

to account for the waves, and they were cabled together.

This is one of the remaining bridging sections. The round surface

that you can see at the corner is where they sat on the pontoon.

The rounded surface allowed for the flex that was inevitable from

waves and from vehicles passing.

Because of tides, a special floating piece was required at the end.

There were two bridges out to the pier, one for empty traffic

going to the pier, one for full traffic coming to the beachhead.

Most pontoons were made of concrete to conserve steel. Some pontoon sections, like the one at left, were more securely

attached to the bottom. These steel pontoons were rigged to float up

and down with the tides through poles that sat on the bottom. The middle bridge span

you can see is different than the ones on either side. It is

built to telescope, or expand and contract to account for tides and the

movement of vehicles.

These are some of the remains of the pontoons.

There were seven platforms making up the piers. They could

be connected with expandable bridges and rectangular floats.

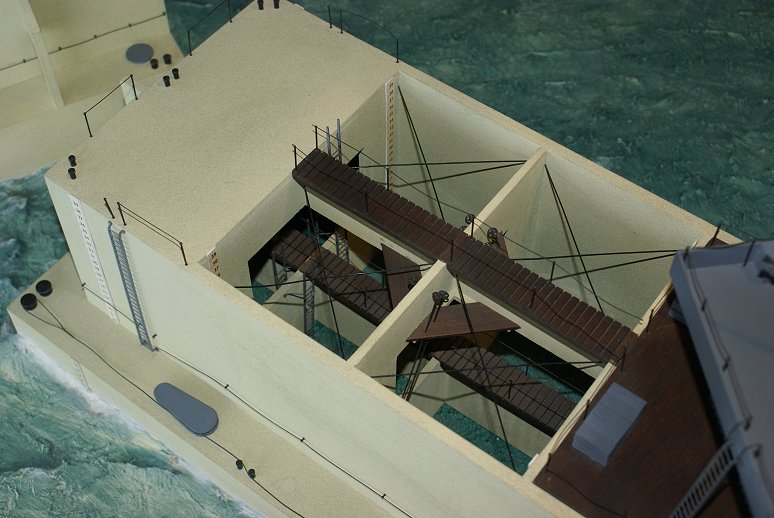

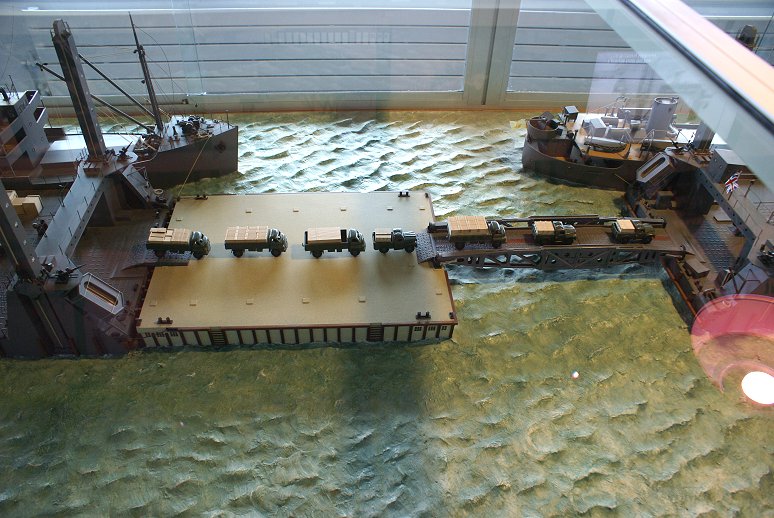

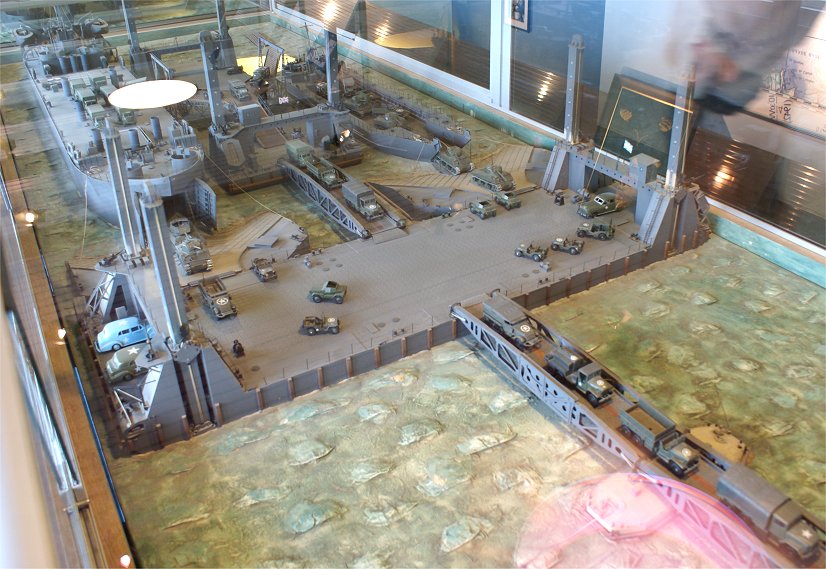

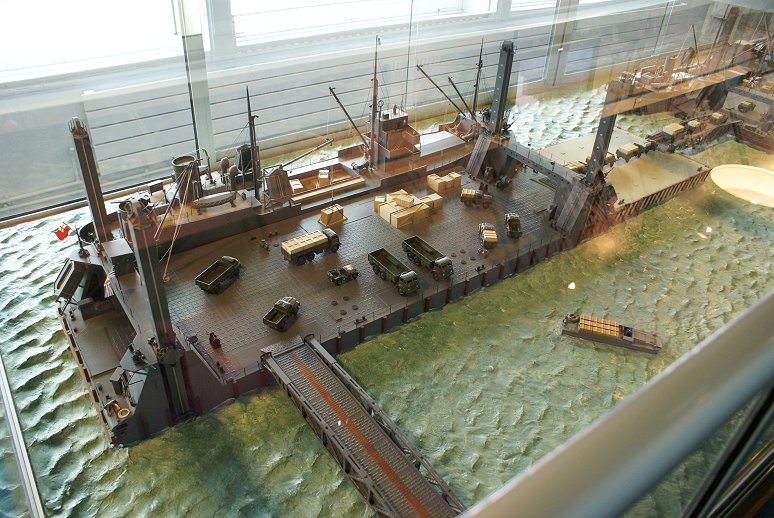

LST Unloading

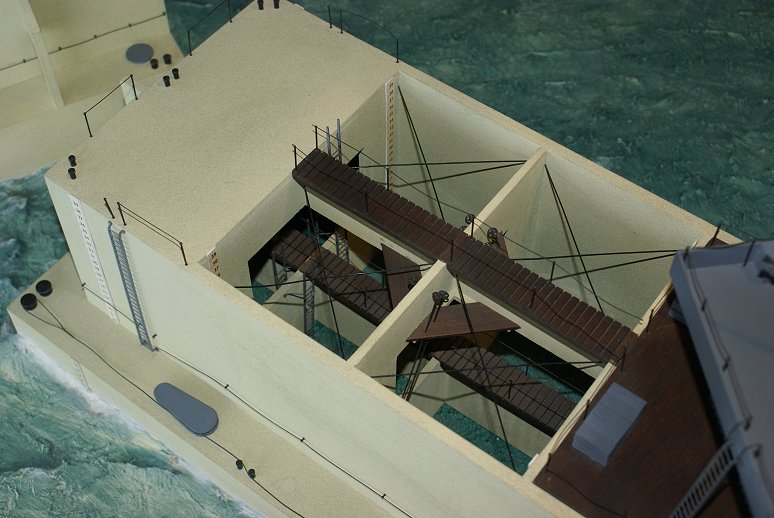

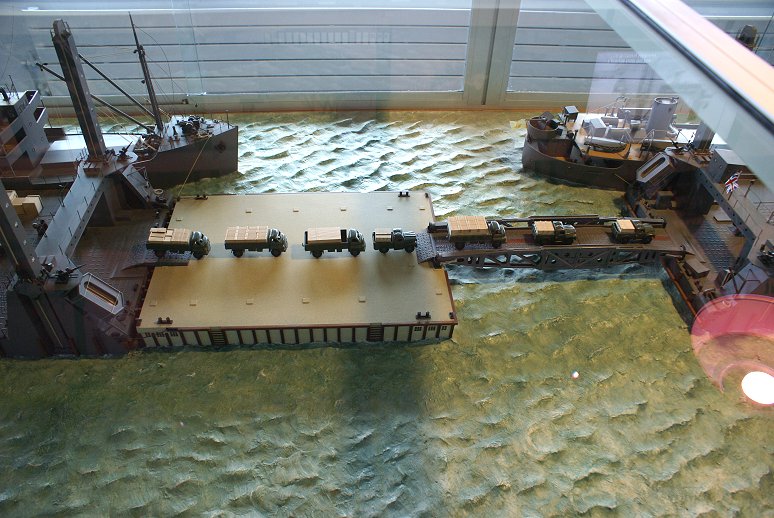

This is a section designed for unloading LSTs, vehicles which would

ordinarily beach themselves to debark directly onto the beach. On

the Mulberry Harbor, a flating wedge was designed for the LST to beach

itself and unload from its bow. In addition, the LST could be

unloaded from its side, making for a much quicker operation. Two

LSTs could be unloaded in less than an hour. And unlike a beached

LST, one unloading at Mulberry would not have to wait many hours for

the tide to allow them to leave, which could take six hours.

Like the pontoon bridge, the platforms of the piers were designed to

move up and down with the tide on poles that rested on the bottom.

This meant that the ships, the platforms, and the bridges were

always at the same level, insuring that the harbor could be used around

the clock.

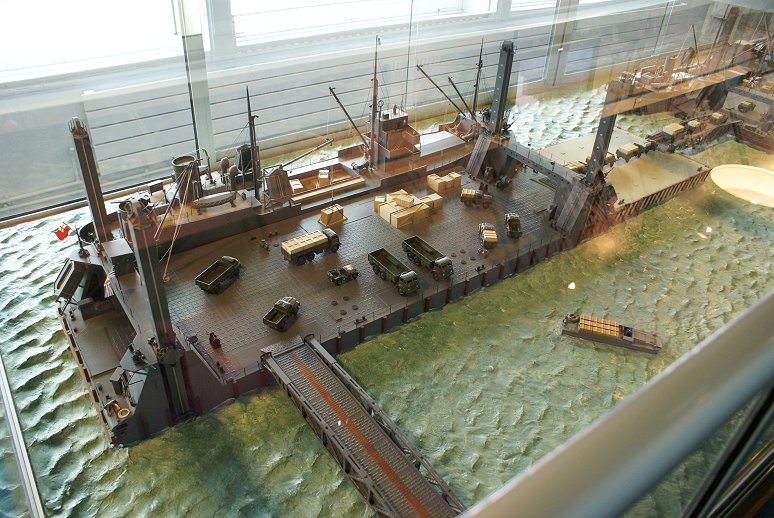

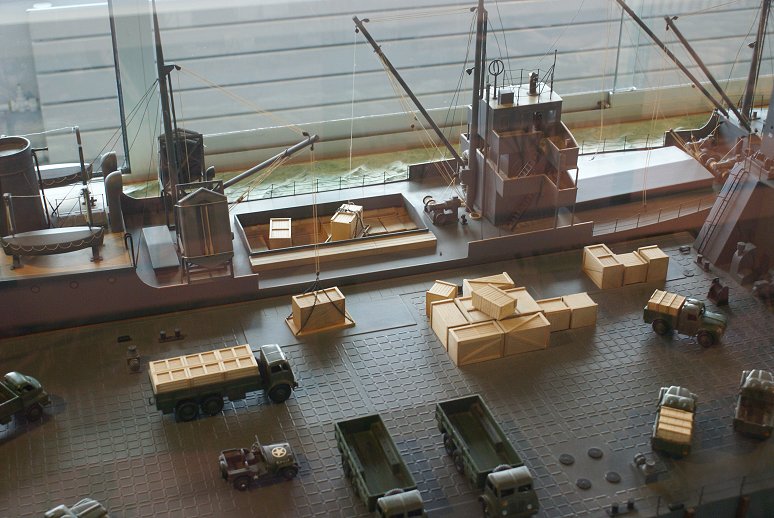

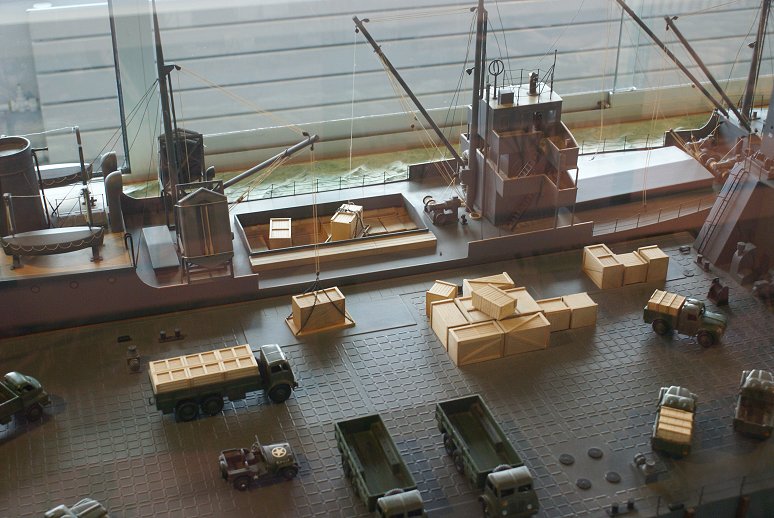

Some platforms were used for unloading Liberty ships. Cranes were

used. Too late, it was determined that conveyor belts might have

been more efficient. The small vessel in the water is a DUKW, an

amphibious truck. A surprising percentage of the cargo was

transported to shore by DUKW.

Also part of the logistics effort was 'PLUTO', a pipeline under the

Channel made of lead, rubber, and steel - designed to bring fuel to the

Allied troops.

Despite the efficiency of the Mulberry Harbor, the majority of men and

materiasl arriving in France were deposited the old fashioned way, on

the beach. Because of this, and the failure of the Mulberry at

Omaha Beach following the gale, some people question the wisdom

and usefulness of the Mulberry Harbor. However, it did give the

Allied command the confidence to make a landing away from a major port,

in an areas which were much less well defended.

Copyright 2010 by John Hamill