Although the Austrian to the south was his greatest threat, Russia to the east was also at war with him. Slow to become heavily involved, in January of 1758, a Russian army under Fermor captured Konigsberg then overran East Prussia. Looking to advance west, the Russians considered combining with the Swedish army on the Baltic coast but instead opted to join up with the Austrians. Advancing through Poland, on August 15, 1758 Fermor's Russian army besieged Custrin on the Oder River, dangerously close to Berlin, which was 50 miles away, and the Brandenburg heartland.

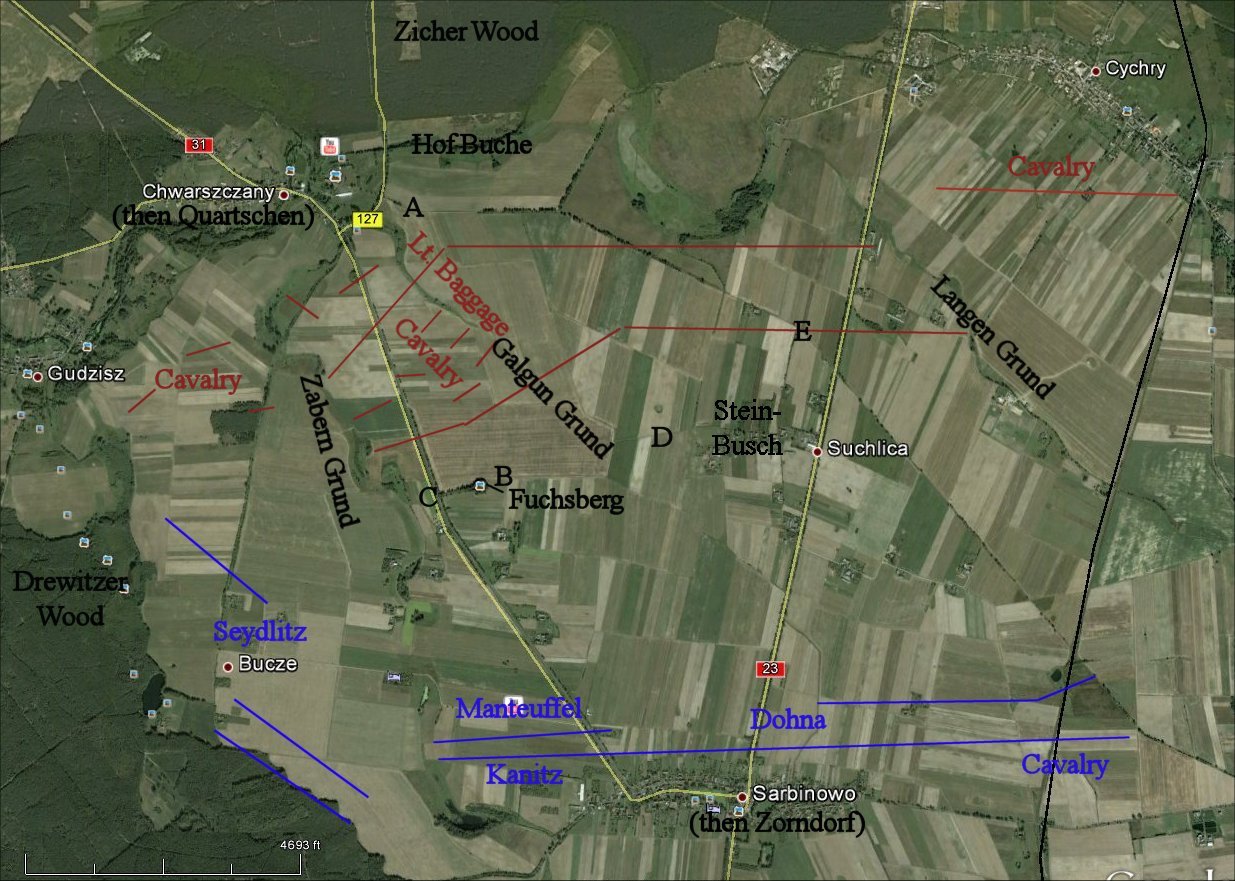

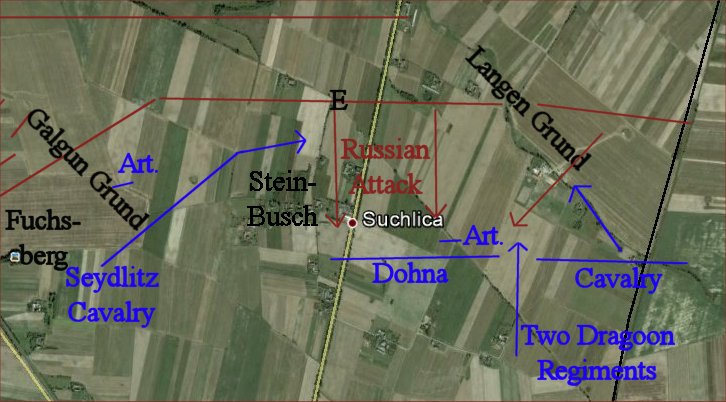

In a complex series of maneuvers, Frederick marched north to face the Russians, followed by the Austrian army, hoping to join the Russians. Frederick moved quickly as he was understandably fearful of being massively outnumbered by a Russian-Austrian combination. Frederick joined up with a Prussian force under Dohna, giving him 37,000 men, and Fermor lifted the siege of Custrin.

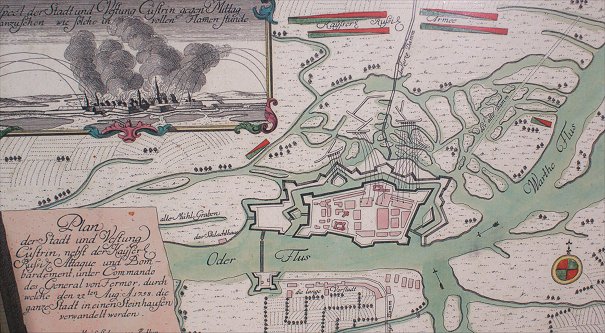

Siege of Custrin

Custrin

Frederick had been imprisoned in Custrin by his father, so the place had many memories for the king. Destroyed in World War II, the Prussian fortress is now being studied and restored.