Ironbridge

Eighteenth century Britain, with a much smaller population than some rivals like France, possessed military power completely out of proportion to its size. This was due in no small part to the nation's economic strength. Foreign trade developed the financial system, allowing the government to borrow enormous sums during wartime at low interest rates. This was an enormous advantage during war since Continental allies could be subsidized and victory was often to the nation which could endure war the longest. Because of the Glorious Revolution of 1688, Parliament - and not the king - largely controlled taxation and spending, and as a result, taxes went through the roof! Unlike less well developed countries, however, Britain could tolerate much higher taxes. A more primitive agricultural economy, like that of France, required 80-90% of the people to work as farmers, and famines and starvation were still a real threat. There was little profit available for the government to tax! In Britain, however, agriculture was much improved, allowing around half of the people to do things other than farm. And unlike France and some other countries, in Britain there were plenty of people who didn't see going into business as a sign of social inferiority.

In previous times, however, expansion of industry depleted the forests, creating an energy crisis which largely undid much of the economic progress. Now, with the development of coal as a substitute for wood, mankind's energy supply was no longer limited to the sun's annual output. Essentially, the sun's stored energy from millions of years ago could now be used.

Early on, with transportation still primitive, industry developed where natural resources like iron ore, limestone, coal, and clay could all be found in close proximity. One such place was the Ironbridge Gorge, which was connected to the port of Bristol by the Severn River.

The Iron Bridge

A marvel of its time, this iron bridge over the Severn, built in 1779, gave this gorge its name and became a symbol of the Industrial Revolution. By the 1770s, the gorge was already an industrial center, and the prefabricated parts that formed the bridge are thought to have been made at the nearby iron furnaces. Abraham Darby III had the toll bridge built for six million pounds, around twice the estimated cost, forcing him to incur massive debt.

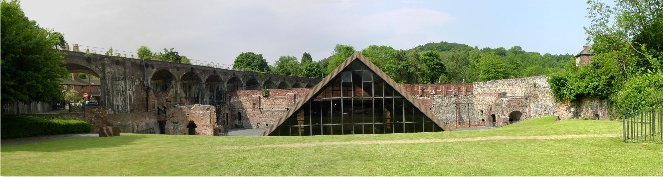

Darby Iron Furnace

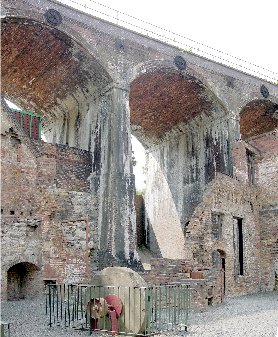

Iron furnaces, much like this one owned by Abraham Darby, date to medieval times. Appropriately, however, Mr. Darby's has been roofed over and turned into a major tourist attraction. To create pig, or bar, iron, wood was smoldered into charcoal, which, along with iron ore and limestone, were dumped into the top of the furnace.

By the early 1700s, however, Darby developed the technology of using coal as a substitute for charcoal by turning it into coke, which removed its impurities. The iron industry was no longer limited by the proximity and abundance of wood, and iron became cheap. Bellows stoked air into the fire from openings like the one on the left side of this furnace, creating a raging fire within. Later bellows were steam powered, removing the need even for water power. The limestone bonded with many of the impurities in the molten iron ore and floated to the top. When all was ready, the molten iron was released as a stream at the prominent opening visible in the picture and flowed into forms in the ground. When it cooled, it was pig iron which would then be made into any number of different items - stoves, tools, or even an iron bridge. Although the owners were Quakers, it is now thought that they cast cannon barrels during the War of Austrian Succession in the 1740s.

The Darby House is now a tourist attraction.

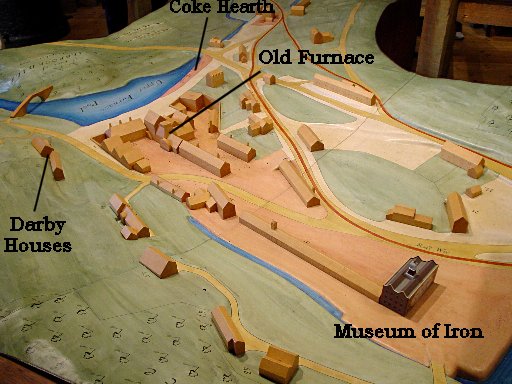

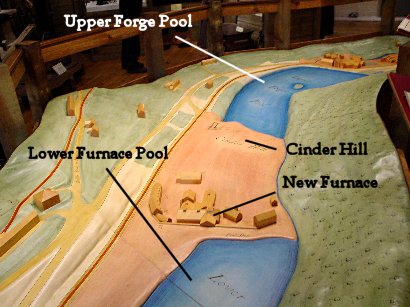

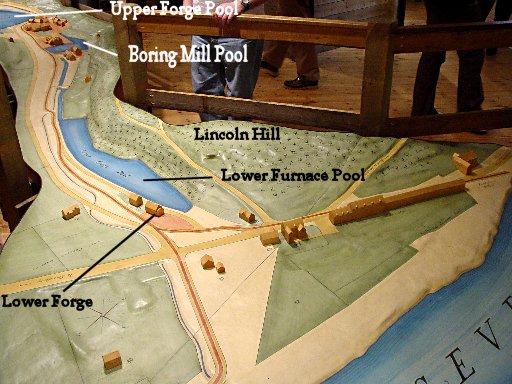

The Darby facility was located along a stream which empties into the Severn. The dioramas will show the facility from top to bottom. Coal was piled around brick chimneys at the Coke Hearth and smoldered into coke. The coke could be used at the Old Furnace, the same one shown in photos above. A small iron bridge crossed the Upper Furnace Pool, and a railway/plateway, shown by the red lines, descended down to the Severn.

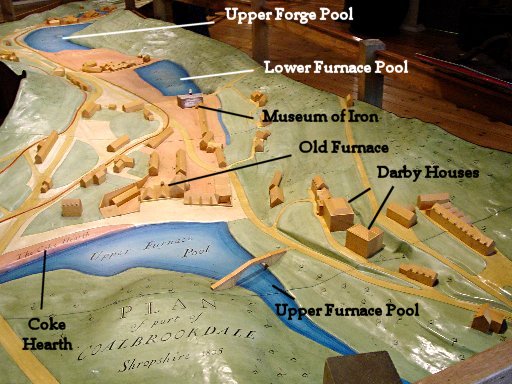

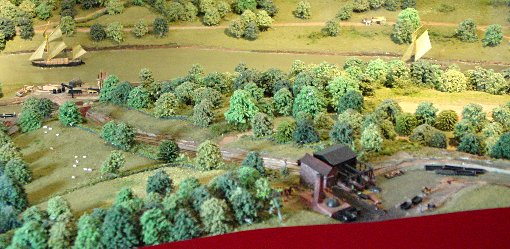

This is the same area, only this time looking downstream. Water was also stored downstream in additional pools to be used for other industrial purposes.

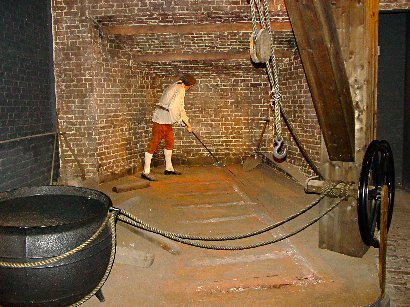

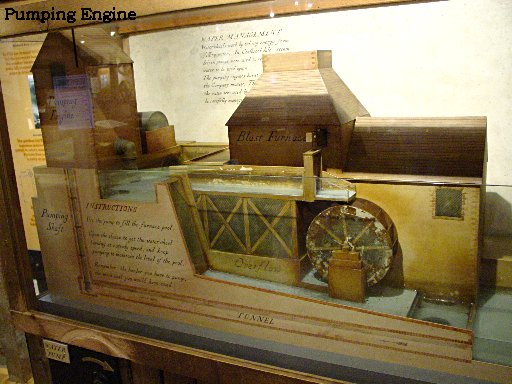

This furnace model shows how the water wheel powered the bellows. A steam pumping engine could then move the water back up to the Upper Pond for reuse.

New Furnace

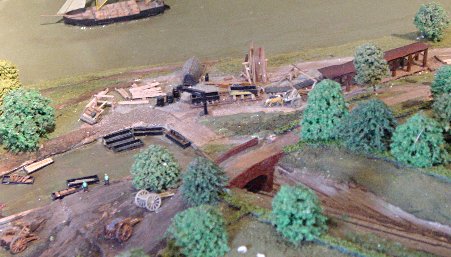

This is looking downhill. Another furnace here, dating to 1715, could also use water power. Slag produced by the furnace was dumped on Cinder Hill. Here, bad castings were also broken up to be once again put into the furnace. Items were cast in Moulding Rooms next to furnace. Grinding Rooms were also nearby for finishing items.

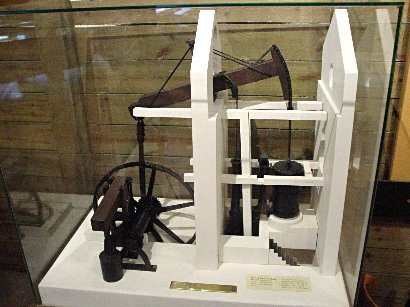

Further downhill from the new furnace was the upper forge. With hammers originally powered by water, in 1785 a Boulton and Watt Hammer Engine like this was installed where it worked along with water powered hammers.

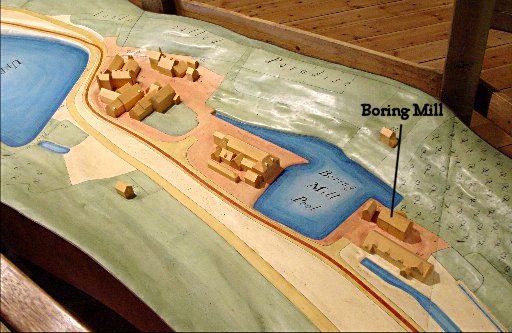

Water from the Upper Forge Pool entered the Boring Mill Pool. In summer, water was pumped from Boring Mill Pool back up to Upper Forge Pool.

Looking Uphill from the Severn

At the Lower Forge, water power was used to pound iron into plate for items like pans or shovels. Limestone used in the furnaces was mined on Lincoln Hill, and the long building on the right was Nailer's Row. The plateway splits and heads both up and down the Severn.

Horse Drawn Plateway

Plateway Tracks at the Wharf

Thevenick Steam Engine

Calcutt Ironworks and Cannon Foundry in Severn Gorge

Enginuity and Museum of Iron Near Ironbridge

Coalport Near Ironbridge

Coalport was a center for pottery production. Like the iron industry, the pottery business here was aided by the proximity of raw materials.

Canal and Inclined Plane

Railroad Bridge

The development of cheap quality iron, which was pioneered in the area, made steam engines and railroads possible. Now with much lower transportation costs, the major advantage of the Ironbridge area, the close proximity of raw materials, no longer mattered. Raw materials could be collected wherever they were cheapest to obtain, then taken to major cities like Birmingham and Manchester where they were more cheaply made into the final product. The Gorge area declined in importance, but the world as a whole became much richer.

Dr. K Meets Abraham Darby While the Pleasant British Lady Enjoys Her Job

And perhaps that's why these two people are so happy and enthused. Thanks in no small part to the great economic advances brought on by the Industrial Revolution, most people in the Western world survive childhood, and adults don't die from drinking the water. Famine and starvation are unknown in the Western world, making poverty purely relative. In fact, the modern poor in the West are richer than kings of the 18th century, who could never have even dreamed of cable TV and the internet.

Britain's early lead in industrialization helped spread the use of the English language - and of democracy itself. Although initially protectionist, Britain, perhaps because of its economic advantages, encourage free trade worldwide starting in the early 1800s. With financial interdependence, there was no catastrophic European war from 1815 until 1914. After two world wars with millions of dead, Europe is once again at peace, and perhaps not coincidentally, financially and economically interdependent. Prosperity created by freedom, individual initiative, and self interest - not idealism and utopian dreams - has made the world a better and more peaceful place.

Content is copyright 2005-2006 by John Hamill.