|

|

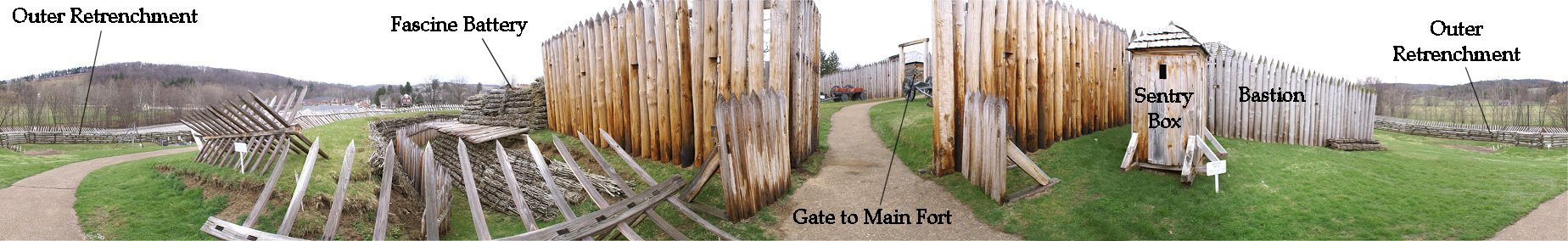

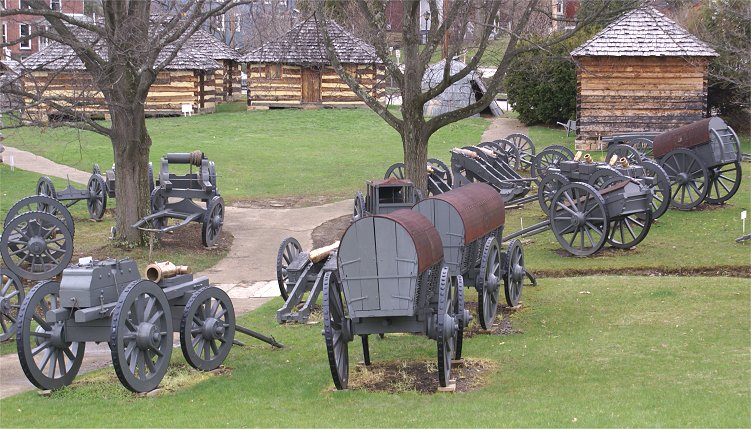

| We just came through the gate at left-center in the above photo. The Fascine Battery

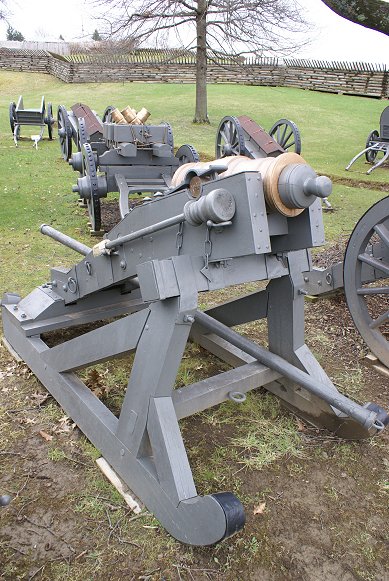

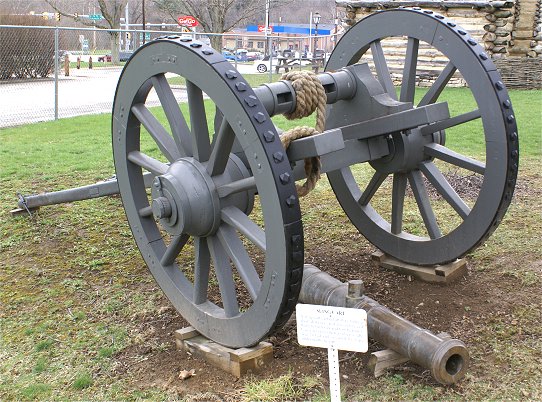

itself is at right-center. The triangular device at left is a gin,

used to lift artillery barrels off their carriages. Also note the two

sunken mortar pits. The photo at right shows several fascines in the foreground and another view of the stockaded ditch in front of the battery. Now let's go inside the square fort. |

|

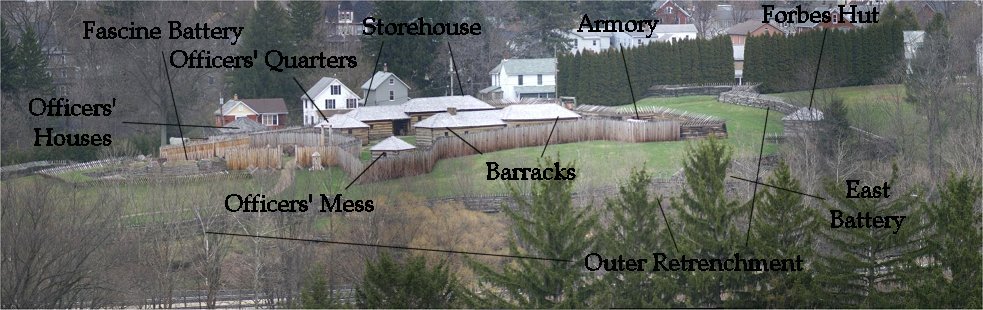

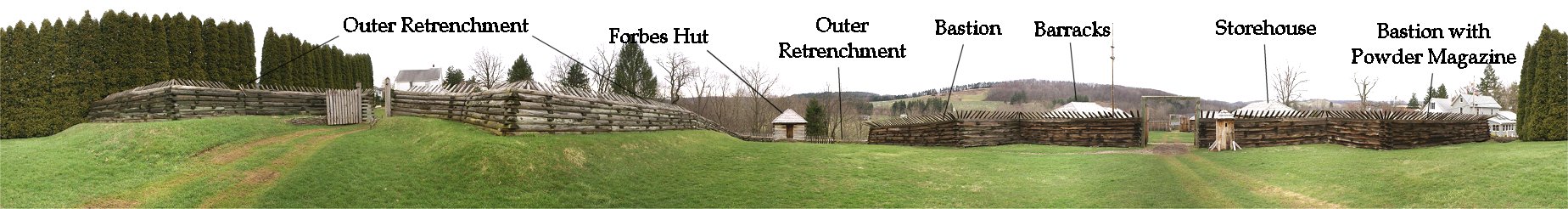

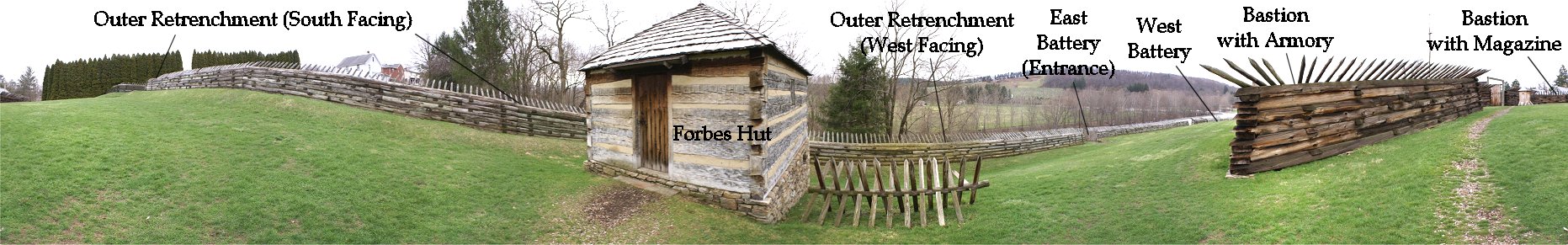

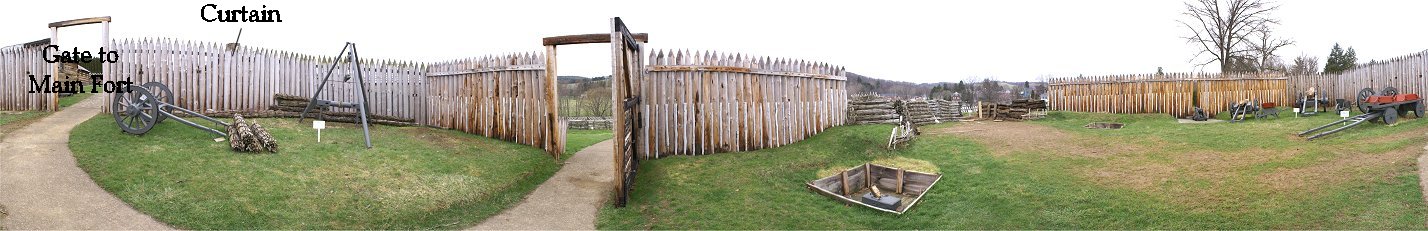

| We just came through the gate on the right of the panorama.

This gate passes through the

stockade portion of the square bastioned fort. The gate at left

passes

through a much more substantial wall. (See photo at right.)

Inside the square fort is a storehouse, a barracks, officers'

quarters, officers' mess, an armory, and the powder magazine. |

|

|

|