Three Pounder "Grasshopper"

At Guilford CH NPS Visitors Center

Light guns like the 3 pounder were not new in the Revolution. In the early 1600s Gustavus Adolphus fielded light guns very effectively, usually in support of a specific regiment, but their use goes back to the infancy of gunpowder artillery. Although largely ineffective against other artillery, light guns were effective anti-personnel weapons and improved infantry morale.

Larger guns were formed into batteries and deployed along the line of battle. By the Napoleonic Wars of the early 1800s, most European armies had adopted the 12 pounder as the standard battery field piece, while the 9 pounder was more common in British service. These larger guns were effective in silencing enemy artillery and killing enemy infantry and cavalry, but during the American Revolution, the British rarely fielded anything larger than a 6 pounder because of the difficult roads in America. They were often used in small groups like larger guns. Fewer and smaller guns along with difficult logistics, open order infantry formations, and a smaller percentage of cavalry tended to make battle less decisive, a significant hindrance to the British war effort.

Park Service Sign

Although eighteenth century weapons may seem crude today, at the time they were expensive leading edge technology. Many decades, in fact centuries, of refinements had been made to artillery.

Iron gun barrels were easiest and cheapest to construct but were somewhat heavy, and heavier barrels needed heavier carriages. Guns were pulled by horses. Unless it was readily and reliably available, forage to feed the horses was transported to the army on horse-pulled wagons. These transport horses, in turn, had to be fed, requiring additional horse-transported forage - in a nearly endless cycle! So there were great incentives to reduce weight, and since competing bronze guns had other advantages, by the 1700s iron guns were mainly used aboard ships where weight was less important.

Bronze, an alloy of about 90% copper and 10% tin, was more expensive than iron, probably around six times more expensive. Bronze as a material is actually heavier, but it made a more durable, stronger and thinner barrel which was therefore lighter than its iron counterpart and which therefore required a correspondingly lighter carriage. Bronze was less likely to burst because it was more flexible. It was also more durable, and the metal was more easily reused after the gun was worn out.

As the park service sign says, these guns were cast solid then bored out. This made for greater accuracy as the bore was better aligned with the gun's exterior, and it also allowed production of guns in greater numbers. The more precise boring technique also allowed a reduction in windage, the gap between the cannonball and the bore. Another artillery development was the spherical powder chamber with ignition near the center of the charge. This produced a quicker, more powerful explosion. These two developments reduced the powder needed per shot by half - to one third of the weight of the ball, allowing a much thinner and lighter barrel. (In the early days of gunpowder artillery, a charge of several times the weight of the ball was used.) Lighter barrels allowed lighter carriages. The 500 pound weight listed is a truly amazing achievement.

Britain was not alone in these developments. Austrian developments in the 1750s led to an artillery arms race on the Continent, and France soon reformed its artillery. The new French 12 pounder of the Gribeauval system was roughly half the weight of the gun it replaced. With guns more numerous and more easily deployed in the field, and with developments and experimentation with light infantry and columns, the way was paved for the decisive battles of the Napoleonic era.

Incidentally, in Britain, cannon boring technology made possible the high pressure steam engines which were a vital part of the Industrial Revolution - an event which would make modern Western man as rich as any king of the eighteenth century.

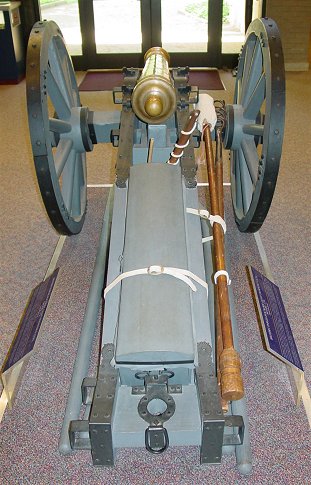

The Front View

As with all field artillery of the era, the spokes of the wheels extended outward at an angle from the hubs, forming a saucer shaped wheel, to give a slightly softer ride and give better strength in cornering. This also tended to keep mud from flying into the faces of troops on the march. Since a vertical saucer shaped wheel would otherwise encounter greater stress, the wheels were slanted so that the lower spokes were vertical. And, since the slanted wheels would also create stress, axle tree arm (projecting from the axle into the hub) was tilted forward.

A water-filled bucket was used for sponging the barrel after each round. Although the British 3 pounder and many other European armies used cartridges, for larger guns, the British used a ladle to load powder into the barrel. The wooden poles, called handspikes, were placed in the carriage's iron fittings to move the guns. Several men with handspikes could carry the cannon over rough terrain or the whole piece could be disassembled and carried by pack animals.

Detail

You can see the touchhole at the top of the barrel and the makers' names, Jan and Pieter Verbruggen. Below the writing are the numbers 1:3:10. This is the barrel's weight. The first number is hundred weight, the second quarters of hundred weight, and the third pounds. Since a hundred weight is 112 pounds, this barrel weighs 206 pounds. In comparison, a Prussian 3 pounder barrel from twenty years before weighed 455 pounds, not much less than the weight of an entire "Grasshopper." For further comparison, markings on the barrel of a 3 pounder on display in the Tower of London dated 1685 indicate a weight of 891 pounds.

To prevent any material in the barrel from staying alight during swabbing, a crewmember covered the touchhole with a piece of leather on his thumb, a job which could become very uncomfortable after a few firings. Propping up the barrel is the wooden wedge, or quoin, used for vertical aiming - a somewhat dated technique and possibly an inaccuracy in this reproduction. Screws to elevate the barrel had been developed in Sweden in the early 1700s, and they were adopted in France during the 1760s as part of the new Gribeauval system.

Detail

Compared with modern propellants, 18th century powder was quick burning. Today's slower burning propellants mean that the projectile can accelerate along the entire length of a much longer barrel and attain a much faster muzzle velocity. Many eighteenth century field guns were limited to a length of around 14 times the caliber, or width of the bore - considerably shorter than the guns which preceded them. British guns generally lacked the ornamentation of early artillery pieces and guns of other European countries, and the Grasshopper had even less decoration than normal. Notice, however, the British broad arrow, the aiming notch on the end of the barrel, and the reinforcing bands - an unnecessary carryover from the past which would be eliminated from guns in the early 1800s. During manufacturing, cannon barrels were cast vertically with the muzzle on top. The weight of molten metal would strengthen the breech area, but tin would settle more toward the bottom leaving the muzzle weaker. To compensate, muzzles were strengthened by flaring them out into a swell, but at the cost of slightly greater weight.

Among the many changes made over the decades was not only the reduction of barrel weight, but the refinement of its weight distribution on the carriage. Trial and error led to the lengthwise position along the barrel of the trunnions, the round projections of the barrel resting in the carriage topped by iron mounts. The trunnions tended to be near the barrel's center of gravity to ease vertical aiming. Another refinement was the position of the trunnions over the axle; these weight distributions had to account not only for the gun's aiming and firing but also for its transport. By the 1750s it was found that moving the trunnions from the underside of the barrel to the middle reduced stress on the carriage. Clearly, a lot of thought and refinement was put into the design of cannon.

Diorama at Tannenbaum Park

This diorama shows three pounders in action. Behind the guns are the limbers used secondarily to store ammunition. Developed originally in the 1680s, limbers began mounting ammunition boxes after 1750. During transport, the trail of the gun was attached to the limber. With the three pounder, a single horse could pull both gun and limber.

Rear of the Gun

Most guns had a quick source of ammunition in sideboxes astride the barrel. This three pounder also had a box along the trail for storing miscellaneous items. To the right of the trail, you can see the sponge used to put out any remaining fire in the barrel before inserting a new round. Failure to do this properly could lead to premature firing as the rammer (the other end of the sponge) was used to push the new round down the barrel. Theoretically after each round the double corkscrew called the worm was run down the barrel and twisted to remove any remains of wadding or cartridge from the previous round.