Tilbury Fort

The famed 1667 raid by the Dutch navy reached Gravesend far up the River Thames before it returned downstream to threaten the Chatham dockyard on the Medway. A small tower fort from the reign of Henry VIII already existed at Tilbury on the north bank, opposite Gravesend, but it was completely inadequate for the times. In reaction, Charles II started construction of a large fort in 1672. Two faces of the fort would dominate the river while another three would provide protect from land attack. In 1716, two large gunpowder magazines were built in the fort, which became Britain's primary powder store. Although modified somewhat over time, Tilbury Fort is a fine example of military architecture of the seventeenth century.

Water Gate

Built to impress visitors arriving from the river, especially foreign ones, the Water Gate is unusually decorative and is thought to have once included a statue of Charles II in its center. The guard house on the left held the twelve men who guarded the gate. The upper floor was the fort's chapel.

Let's go through the gate and take a walk, counterclockwise, around the fort's interior.

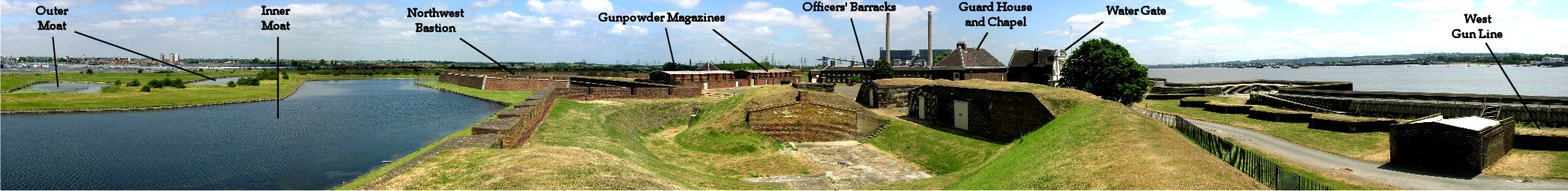

From Tip of the West Bastion

From here, you can see the fort's two wet moats, both formidable obstacles to any attack from land, but even more so since earthworks manned by infantry protected the dry land between them, making any crossing of the outer moat a costly proposition.

The majority of the photo is taken up by the West Bastion. You can see that the bastion's flank, or shoulder, covers the face, or front, of the Northwest Bastion, as well as the curtain wall between them. An expense magazine inside the bastion would hold ammunition ready for the use of the guns nearby, while protected from direct and indirect fire.

The Gunpowder Magazines in the distance held much of the nation's powder supply. These buildings are parallel to the northern wall, of which you can see the roof of the Landport Gate behind them. Further right are the Officers' Barracks, the Guard House, and the Water Gate. On the far right is the West Gun Line, additional protection from attack from the river.

From West Curtain Wall

Along the Western Curtain, visible on the far left, you can see all of the buildings of the parade ground that we saw in the previous picture and more. The foundations of the now demolished Soldiers' Barracks can be seen, as well as the two river facing curtain walls, the Southeastern one being marked, and the other being parallel to the Guard House and Chapel. The Southeast Curtain has been heavily modified from its original form in order to mount more modern weaponry. On the right is a good view of the West Bastion and the expense magazine that dominates it.

Landport Gate

From along the flank of the Northwest Bastion, you can see the north curtain wall and the Landport Gate which passes through it. With two drawbridges across the inner moat to its front, the relatively little used Landport Gate was well protected. Although not clear here, the grassy area across the bridge, the ravelin, contained earthwork fortifications. Another drawbridge crossed over to the covered way separating the inner moat from the outer moat. The route crossed over to the redan (which featured a two story redoubt) within the outer moat, then crossed over another causeway to completely exit the fort.

Northeast Bastion

On the far left of the picture the brick wall outside of the Gunpowder Magazine is visible, followed by the pointy-topped Landport Gate. The curtain wall then takes a 90 degree turn to become the Northeast Bastion, which dominates this photo. Like the West Bastion, an expense magazine is in the center of this bastion also. The gun emplacements and serving rooms on the right of the bastion date to the 1870s. On the far right, once again you can see the walls of the Gunpowder Magazine, to the left of which is the end of the Officers' Barracks.

|

|

|

|

Gunpowder Magazine

As these buildings were built in the early 18th century, they combine practicality with decoration. Unless extreme precaution was taken, powder was liable to either explode or deteriorate. The thick inward tilting brick outer wall, as well as the heavy buttresses on the buildings themselves, served primarily to send any potential explosion upward and not outward. To help prevent an explosion, no iron was used in the magazines. The doors and other necessary metal, on the barrels themselves, for instance, were made of copper. Wooden pegs were used in the floor, which was elevated in order to keep the powder dry.