A Litany of Incompetence - Staff, Headquaters, and the Civil War

"... I cannot have my orders carried out!" Robert E Lee

C-Cubed and Staffs

Civil War generals, especially Lee, are often criticized for having inadequate and inefficient staffs, and these criticisms are not without justification, especially for the first half of the war. Many authors mention the staff issue only in passing without expounding upon the issue, and many authors make no comparison with European armies. There are few books dedicated to the subject, with J Boone Bartholomees' "Buff Facings and Gilt Buttons" among them. Bartolomees concludes that Lee's staff, larger than it appeared, was large but at the same time not large enough. Because of varying accounting methods, numbers are difficult to gauge, but Confederate HQ staff strength at First Manassas was 30-40, being a combination of Johnston and Beauregard's staff. Lee's staff, often described as 14 general staff officers, may have been just part of a much larger HQ group of up to 695 total. This figure was around 390 in 1863-64 and around 80 at Appomattox. That being said, what these numbers actually count is not clear, but they seem to include numerous support personnel such as clerks and couriers in addition to actual staff officers. Major Taylor had five clerks, for example, and 25 couriers were used in the Second Manassas campaign to send messages between Lee and Jackson, and couriers were also used to send messages to and from signal flag and semaphore stations. Lee sometimes rode with 2-3 members of his staff, sometimes he rode alone. He was even known to borrow officers from other units when all his staff was occupied! (Bartholomees 7-12, 203, 206, 213)

Michael Hardy, in his book "Lee's Body Guards", discusses a unit that served not only as body guards but most frequently as couriers. Early in the war, couriers were cavalrymen temporarily detached from their units, but by late 1862, a special unit was formed, the 39th Battalion Virginia Cavalry. The unit was also used for miscellaneous tasks like reconnaisance, searching for stragglers, and escorting prisoners of war. At the beginning of the 1864 campaign, there were 169 men. Typically there were 3-5 companies, with a company at Lee's headquarters and companies at each corps headquarters. Messages sent by couriers were typically written, but when no staff officers were available, couriers were sometimes tasked with delievering oral instructions.

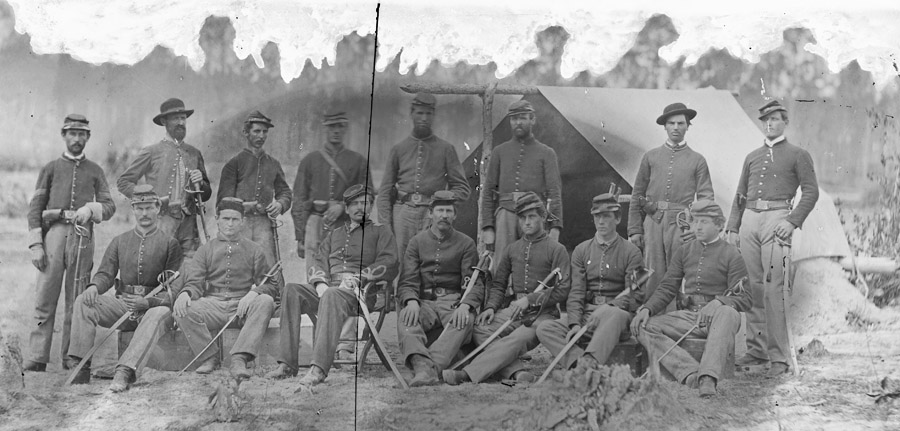

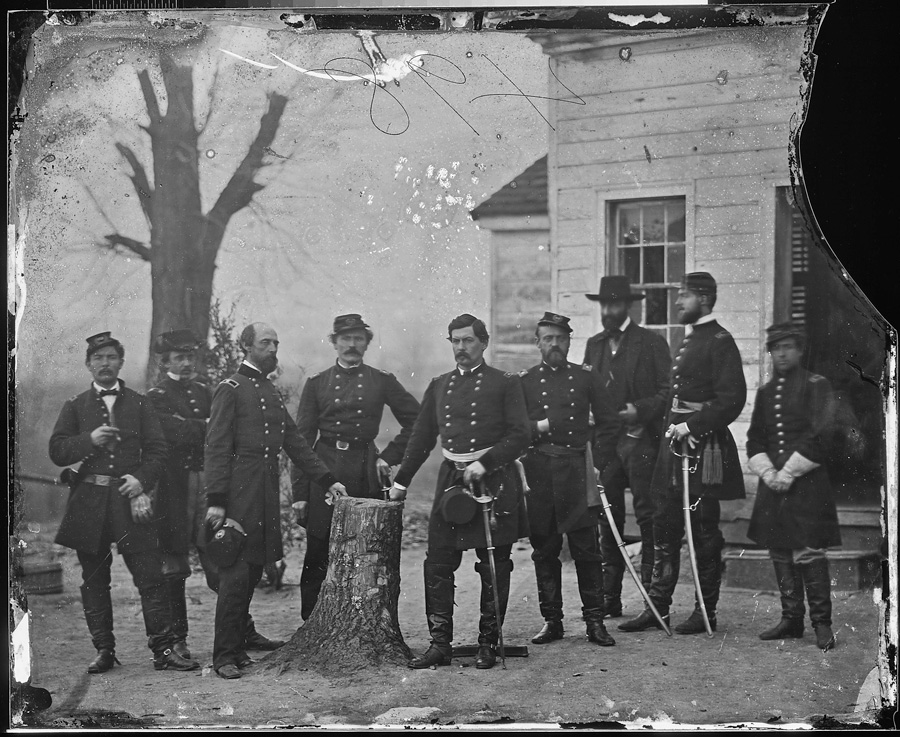

|

| Group of the 2nd Indiana Cavalry at Headquarters of the Army of the Potomac |

An in depth investigation of command, control, and communications explains a great deal about the need for an efficient staff - examples abound of mistakes rooted in poor staff work.

So exactly what functions did the staff serve? Some staff officers worked as administrators, others served more direct military functions. The administrative officers included functions like the quartermaster, commissary, and medical director - although vital we will largely ignore these functions. The military staff included the chief of staff, the adjutant, branch chiefs, and aides-de-camp. It is the military staff that we will focus on as they had a direct impact on how battles were fought. In "The Science of War", GFR Henderson gives good coverage of staff duties and their importance, including reconnaissance, routing of troops, and communication between a commander and his subordinates. Discussing the Confederates, he writes on page 221:

|

|

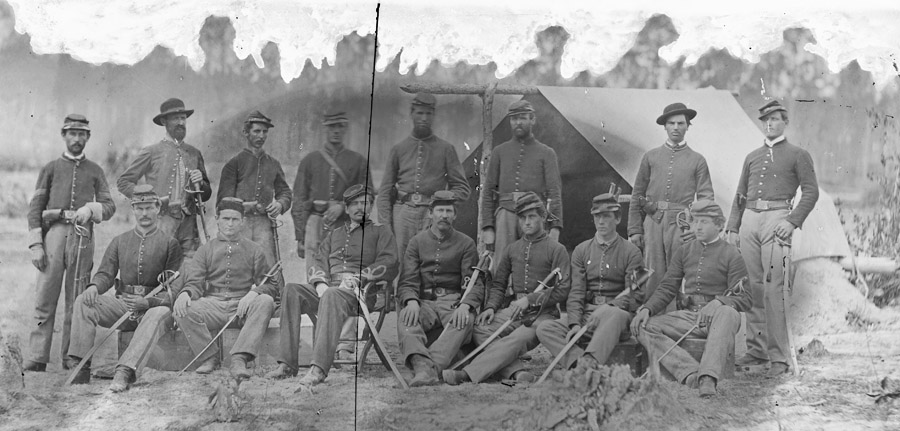

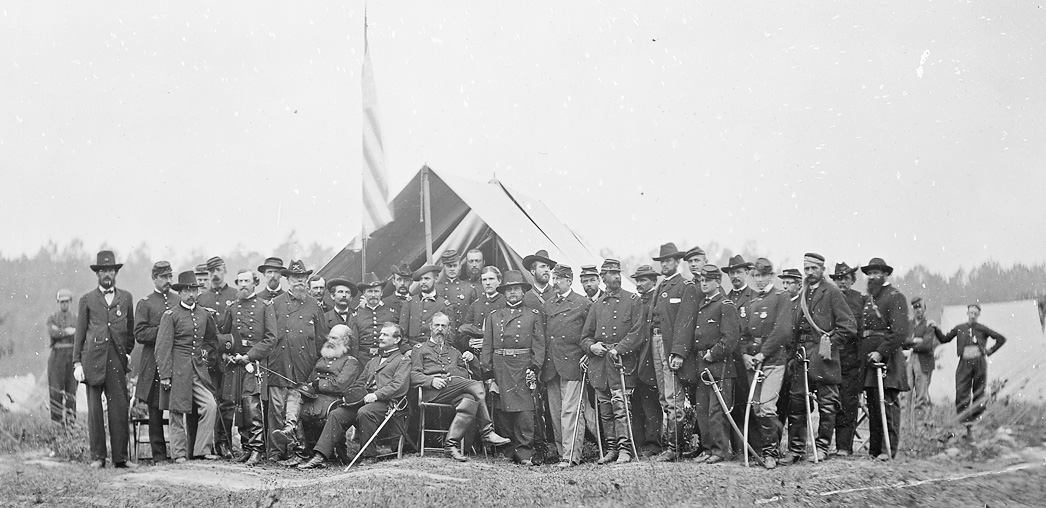

| Gouvernour Warren and the staff of V Corps, twelve in all, although staff officers could have assistants. Warren's HQ is interpreted at the Wilderness battlefield park. |

|

|

|

|

At Pea Ridge, Arkansas, in March 1862, a Confederate army marched around the Union army, attacking it in the rear. A decisive result was possible but the ammunition wagon got lost, so in the second day's fight, the Confederates lost the artillery duel, and the Union army escaped.

The Prince of Joinville, a Frenchman serving with McClellan's army, discussed at length Union staff issues during the Battle of Williamsburg (p52):

"There is no special branch of the service whose duty it is to regulate, centralize and direct the movements of the army. In such a case as this of which we are speaking, we should have seen the General Staff Officers of a French army taking care that nothing should impede the advance of the troops, stopping a file of wagons here and ordering it out of the road to clear the way, sending on a detail of men there to repair the roadway or to draw cannon out of the mire, in order to communicate to every corps commander the orders of the General-in-Chief.

Here nothing of the sort is done. The functions of the adjutant-general are limited to the transmission of the orders of the general. He has nothing to do with seeing that they are executed. The general has no one to bear his orders but aides-de-camp who have the best intentions in the world, and are excellent at repeating mechanically a verbal order, but to whom nobody pays much attention if they undertake to exercise any initiative whatever. Down to the present moment although this want of a General Staff has often been felt, its consequences had not been serious. We had telegraph, which followed the army everywhere and kept communications between the different corps; the generals could converse together and inform each other of anything that was important to know. But once on the march this resource was lost to us, and so farewell to our communictions!

The want of a General Staff was not less severely felt in obtaining and transmitting the information necessary at the moment of an impending action. No one knew the country; the maps were so defective that they were useless. Little was known about the fortified battlefield on which the army was about to be engaged. Yet this battlefield had been seen and reconnoitred the day before by troops which had taken part in Stoneman's skirmish. Enough was surely known of it for us to combine a plan of attack and assign to every commander his own part in the work. No, this was not so. Every one kept his observations to himself, not from ill will, but because it was nobody's special duty to do this general work. It was a defect in the organization, and with the best elements in the world an army which is not organized cannot expect great success. It is fortunate if it escape great disaster."

Confederate artillerist Edward Porter Alexander had this to say on the number of staff officers used during the war,

"Scarcely any of our generals had half of what they needed to keep a constant and close supervision on the execution of important orders. And that ought always to be done. An army is like a great machine, and in putting it into battle it is not enough for its commander to merely issue the necessary orders. He should have a staff ample to supervise the execution of each step, and to promptly report any difficulty or misunderstanding."

"Last Chance for Victory", a book on Gettysburg co-authored by Scott Bowden and Bill Ward, states that Napoleon had more staff officers in a division than Lee did in his entire army at Gettysburg. At Austerlitz, Napoleon had nearly 200 men in his headquarters staff. Each of Napoleon's corps had thirty or more staff officers, and each division had 20 or more. Napoleon was supported by a staff roughly ten times the size of Lee's staff. For the Seven Days, Lee's staff consisted of just 12 officers plus couriers. With time, the size and efficiency of the staff was increased only slightly. Bowden argues that an inadequate staff made it impossible for Lee to coordinate his army effectively. On July 2nd Lee launched an en echelon attack, perhaps because it was impossible to coordinate anything more complicated - each division would attack at an interval after the division to its right. To get all of his divisions to attack simultaneously, for example, would not have been possible. So when Gen. Pender was hit by enemy fire, his division remained in place and the army's attack broke down as it was approaching Cemetery Hill, perhaps saving the Union army.

Gettysburg provides a number of additional examples of staff failures with serious consequences. Longstreet's march on the second day was delayed when it encountered an area observable from Little Round Top, and much time was lost when the troops were redirected. Why was this area not discovered before? A larger and better staff might have prevented this incident and gained valuable hours. R.H. Anderson, commanding a division of Hill's corps, was ordered to attack with short notice after Longstreet had begun his attack, but he was not told the object of the attack or that the original plan, to attack up the Emitsburg Road, had been modified. The attack on Cemetery Hill was repulsed in no small part because of the lack of coordination between the divisions of Early and Rodes. The Union side also suffered from staff problems. Despite visits from Meade's staff, Dan Sickles was never sure where Meade wanted his corps to be, which contributed to his decision to move forward. When attacked, Sickles required reinforcements. When Geary's division of the XII Corps was sent to assist, it marched from Culps Hill not long before the Confederates attacked, and the move was marred by poor staff work. Geary's division was to follow Williams' division, which had not been given specific direction. Geary explained,

"When ordered to leave my entrenchments, I received no specific instructions as to the object of the move, the direction to be taken, or the point to be reached, beyond the order to move, by the right flank and to follow the First Division. The First Division, having gone out of sight or hearing, I directed the head of my column by the course of some of the men of that division who appeared to be following it."

Geary's division became lost and was not able to reinforce the endangered Union left flank. It participated in neither protecting Culps Hill nor saving the army's endangered left flank. Cole's "Command and Communication Frictions" on p54 quotes Union Col. Thomas Rafferty, an officer in Sickles' corps who was not happy with the army's staff. His assessment of his army's staff system is damning.

"My own opinion has always been that the staff of a general commanding the army should be something more than mere clerks to draw up papers and carry messages... They should have known all about our line of battle; have made themselves familiar with its salient points, its capabilities for defense or its facilities for offensive operations. They should have directed and controlled the positions of the various corps; should have been the eyes of General Meade, the brains to plan and, under his direction, the hands to execute; should have seen all the enemy proposed to do, and so prepared their own plans as to checkmate and overwhelm him, as with the proper dispositions they might easily have done. But they did none of these things."

|

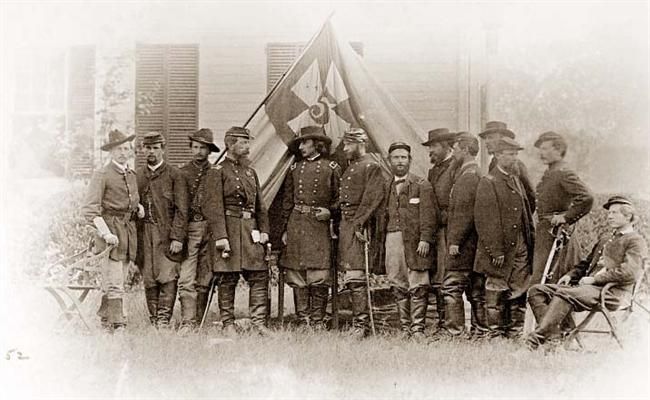

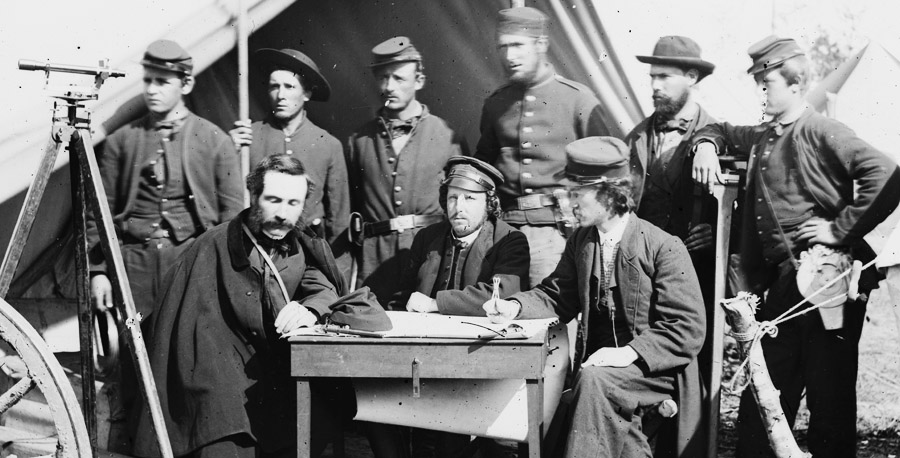

| Topographical Engineers - Camp Winfield Scott, Yorktown, VA May 2,

1862 |

Some historians believe that at Shiloh the Confederates intended to attack the Union army into their flank from west to east, but lack of maps and local knowledge prevented this. How very differently that battle might have turned out without a frontal attack and the resultant bloodbath. An inadequate Union staff can also be blamed for inadequate reconnaissance that made the Confederate surprise attack possible. A Union lack of maps saved Stonewall Jackson from being cut off as he fell back from Harpers Ferry - Union General Shields took the wrong road. Jackson's performance in the Seven Days suffered because Hotchkiss, his mapmaker, was still in the Shenandoah Valley - as Freeman wrote, "with Hotchkiss away, Jackson was not blinded, but his vision was dimmed." In contrast, successful engineer reconnaissance benefited the Confederates at Chancellorsville, verifying the feasiblity of the route around the Union army, and at Cedar Creek, where observation from the northern tip of the Massanutten found the Union flank vulnerable. In the summer of 1862, the Confederates established a map reproduction facility that included the use of photography to copy maps. (Bartholomees 106-8) In the Union army, commercial photographers were allowed to accompany the army in exchange for their producing photos of maps. Tracing was also an effective way to reproduce maps. Printing sometimes was done on fabrics because cloth held up better to rain and dirt. Earl McElfresh's "Maps and Mapmakers of the Civil War" is a veritable mine of information on maps and the work of topographical engineers. Topographical engineers or civilian contractors set about the country, lightly equipped with a small escort, with a drawing board set on the pommel of their saddle where they recorded data. With a compass they gathered the angle of roads, and with a barometer the altitude; distance could be estimated by appearance or number of horse steps. Depth of fords could be measured by the height of water on the horse, and depth determined if cavalry, infantry, or wagons could cross, with wagons requiring 2 1/2 feet or less. Road conditions were recorded - this data affected how much could be transported on each wagon, with macadam roads allowing 2 tones per wagon and dirt roads just half that amount. Grade of slopes also was recorded, with infantry, cavalry, artillery, and wagons all capable of traversing different angles. Information was also gathered from locals, not always voluntarily. Maps included details locations of drinking water as well as fencing, which could be used to corduroy roads, and areas of pine trees within a deciduous forest to help orient the map reader. McElfresh intersperses his book with the effects that maps had on campaigns. In the Peninsula, incomplete maps failed to show that the Warwick River was a barrier to the advance. Lack of maps in the Valley may explain why Shields failed to cut off Jackson's retreat from Winchester. A short time later, poor Union maps may explain the defeat at Cross Keys. At Chancellorsville, O.O. Howard dismissed the warnings of an engineer and dismissed the possibility of a flank attack. At Chattanooga, Sherman failed to understand that his objective was two hills in front, not one. McPherson's death at Atlanta may have been the result of a map error. And on the Union side, the Overland Campaign was marred by bad maps.

Paddy Griffith (p55-56) gives an example of bad staff work at the October 1862 Battle of Corinth. Hoping for a decisive flank attack against the attacking Confederates, William Rosecrans sent his chief of staff to an unengaged division on his flank, but the message was verbal and confused, and the staff officer was forced to return to Rosecrans for a written order. By the time it arrived, the opportunity was lost. During the war, verbal orders were typically followed by written ones, but in this case Rosecrans failed to do so. Poor staff work in Rosecrans' army would lead to disaster at Chickamauga in September 1863. Due to a misunderstanding, Rosecrans ordered a division out of the line in the worst possible place - the area opposite Longstreet's enormous column of attack. A well functioning staff would have kept proper track of unit positions. Elsewhere along the Confederate line at Chickamauga, staff officer Moxley Sorrel relates on page 201 of his "Recollections",Fortunately for the Confederate cause, Sorrel was able to find Longstreet and return with direct orders, and the opportunity was not lost. The system of staff and command philosophy in Bragg's army, however, was shown to be deeply flawed.

|

| George Thomas's wagon - a mobile command post - featured fold-down desks with trays and an awning. |

|

|

| Similar equipment, without the wagon, appears to have been used by the 18th Corps near Petersburg. |

Although there seems to have been progress with staffs through the war, problems continued to the end. Before the Battle of White Oak Road in the spring of 1865, General Chamberlain received five orders from three sources - Grant, Meade, and Sheridan - and each order was incompatible with the others.

William Hazen, a Union general wrote on p423 of his Narrative:

He goes on, discussing another ill coming from poor staff work,

|

|

| City Point Scouts at Secret Service Headquarters Under Joseph Hooker, the Army of the Potomac organized the Bureau of Military Intelligence to accumulate and analyze intelligence. At its peak the bureau numbered 67 men. It cooperated with the Signal Corps, balloons, and the cavalry, but it got much of its intel from a daring group of scouts who went behind Confederate lines for recon and to contact sympathetic civilians. Excellent books by Peter Tsouras discuss these men. |

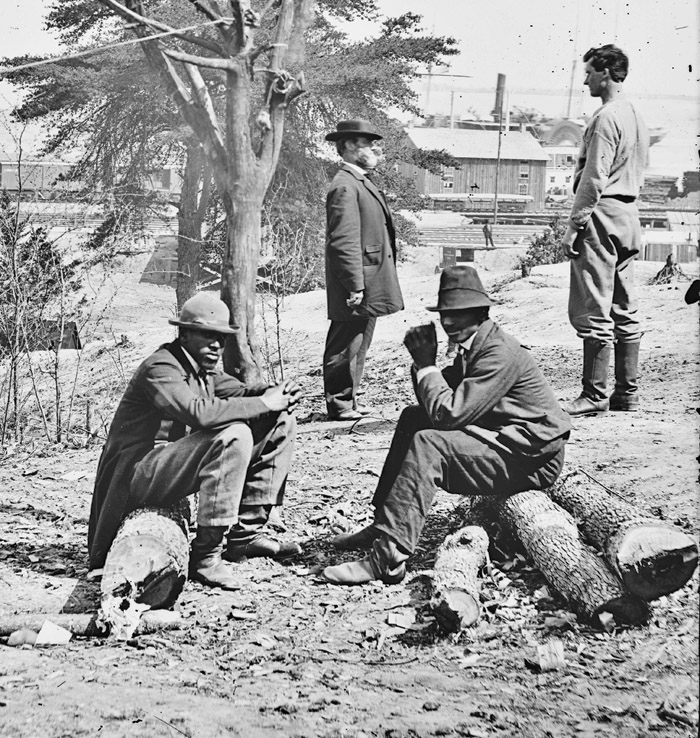

William Wilson, Scout, at Headquarters, Army of the Potomac |

In the Maryland Campaign, Burnside was elevated to grand division command, leaving command of his IX Corps to Reno. The death of Reno at South Mountain resulted in the elevation of Jacob Cox to command IX Corps who had to rely on his smaller divisional staff to manage the corps. The corps' effectiveness at Burnside Bridge suffered as a result. On page 97 of his autobiography, George Crook wrote,

"About 10:00AM, Capt. Christ on Gen Cox's staff came to see me, and said, "The General wishes you to take the bridge." I asked him what bridge. He said he didn't know. I asked him where the stream was, but he didn't know. I made some remarks not complimentary to such a way of doing business, but he went off, not caring a cent... The consequence was that I had to get a good many men killed in acquiring the information which should have been supplied me from division headquarters."

For his part, Jacob Cox had some particular ideas about staff and command which also concern command style. On page 304 of his autobiography, he wrote about a nighttime shift of positions prompted by a recon by McClellan,

"...staff

officers (were) sent to guide each division to its new camp. The selected

positions were marked by McClellan's engineers, who then took members of

Burnside's staff to identify the locations, and these in turn conducted our

divisions. There was far more routine of this sort in that army than I

ever saw elsewhere. Corps and divison commanders should have the

responsibility of protecting their own flanks and in choosing ordinary camps.

To depend on the general(sic) staff for this is to take away the vigor and

spontaneity of the subordinate and make him perform his duty in a mechanical

way. He should be told what is known of the enemy and his movements so as

to be put on his guard, and should then have freedom of judgment as to details."

|

Phillip Cole, in "Command and Communications Frictions in the Gettysburg Campaign" quotes Maj Samuel Melton, a Confederate Assistant Adjutant, who wrote, "The staff deserves earnest consideration. My limited experience in the service has been sufficient to convince me that the importance of an efficient staff has been much underestimated, and that it cannot be overestimated... (W)ell-nigh everything depends upon a competent, earnest, and laborious staff. The Army is childlike, utterly dependent. The general cannot be ubiquitous - is indeed but a man. The staff must make up the complement." Not only was small staff size a problem, the quality of officers was also an issue. Melton thought that staff officers were too young and inexperienced and in general inadequate. In part, this was because, "While promotion is rapid in the line, it comes scarcely at all in the staff; and if at all it is incident attending the promotion of the chief, and not the reward of merit. It is perhaps, in a contest like this, an instance of frailty that men of brains, of enlarged mental and business capacities, will not seek employment, however useful, where there are no rewards; and if they by mistake fall into such employment they are too prompt to leave it for more inviting and promising labors."

General Lee, in a letter to Jefferson Davis about a bill in the Confederate Congress wrote about filling staff positions, "If you can fill these (staff) positions with proper officers - not relations and social friends of the commanders, who, however agreeable their company, are not always the most useful - you might hope to have the finest army in the world." The Prussian General Staff system was very different. Intelligent, promising young officers were selected to serve as staff officers, but they were rotated through line duty in various branches to gain experience in a wide variety of duties, puttin them on track for higher command. Rather than being a dead-end job, in the Prussian system, staff work was a springboard for high command. This system would prove its worth - but only after the American Civil War. |

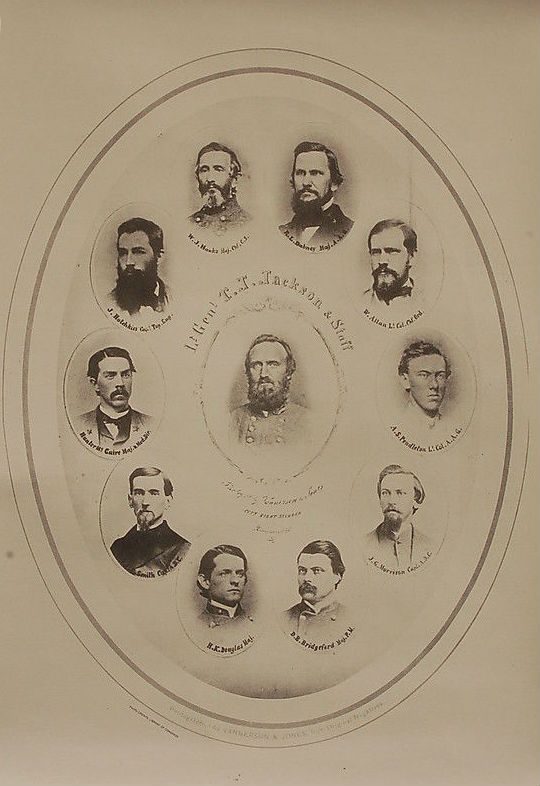

Jackson's Staff - Where are the experienced pre-war officers? They had become generals, so amateurs had staff positions. Henderson on page 687 wrote, "(Jackson) preferred men who would win the confidence of others - men not only strong, but possessing warm sympathies and broad minds." |

|

|

| Signal Corps men were charged with sending messages by semaphore flags, a quicker alternative than mounted messengers, and with recon. At Petersburg, static conditions allowed for construction of towers. | Mobile, field telegraph was first used in the Chancellorsville campaign. Most practical in static situations, Sherman is known to have used field telegraph at Kennesaw Mountain. |

McClellan and Staff of Eight |

Meade and Staff of Thirty-three |

What would have made Civil War staffs useful and efficient? Simply having a staff composed of career officers educated at West Point perhaps would not have been enough. Stating that it took two years for either army to field a trustworthy staff (p226), GFR Henderson wrote that staff duties are best learned not in the classroom but in the field at large scale maneuvers, something the ante-bellum army simply didn't do. Wellington, Henderson states, believed that seven years experience in the field was required to make a good staff officer. (p398) In a letter to Jefferson Davis, Lee explained his staff issues and recommended a corps of officers to teach staff duties.

Sources and Suggested Reading:

Michael A. Bonura, Under the Shadow of Napoleon

J. Boone Bartholomees, Jr., Buff Facings and Gilt Buttons

Bowden and Ward, Last Chance For Victory

David Chandler, Art of Warfare in the Age of Marlborough, The Campaigns of Napoleon

Phillip Cole, Civil War Artillery at Gettysburg, Command and Communications Frictions in the Gettysburg Campaign

Jean Colin, Transformations of Warfare

Christopher Duffy, Instrument of War: The Austrian Army in the Seven Years War

Lee W. Eysturlid, The Formative Influences, Theories, and Campaigns of the Archduke Carl of Austria

Steven Fratt, The Guns of Gettysburg - North & South August 2004

Gates, David, The British Light Infantry Arm, c. 1790-1815

Paddy Griffith Battle Tactics of the Civil War, Forward Into Battle, Battle

Edward Hagerman, The Civil War and the Origin of Modern Warfare

Hardy, Michael C, Lee's Body Guards

William Hazen, A Narrative of Military Service

GFR Henderson, The Science of War

GFR Henderson, Stonewall Jackson and the American Civil WarEarl Hess, Field Armies and Fortifications in the Civil War

Earl Hess, Civil War Infantry Tactics

Ian Hope, A Scientific Way of War

Wayne Hsieh, West Pointers and the Civil War

BP Hughes, Firepower

Prince de Joinville, The Army of the Potomac

Robert K Krick, Stonewall Jackson at Cedar Mountain

McElfresh, Earl B, Maps and Mapmakers of the Civil War

Brent Nosworthy Anatomy of Victory, With Cannon Musket and Sword, The Bloody Crucible of Courage

Lt. Jacques Arnould Obreen, De Noord-Amerikaansche oorlog van 1861-1865

Peter Paret, The Cognitive Challenge of War: Prussia 1806

Christopher Perello, The Quest for Annihilation

Robert Quimby, Background of Napoleonic Warfare

Fred Ray, Shock Troops of the Confederacy

Carol Reardon, With a Sword in One Hand and Jomini in the Other

Justus Scheibert, A Prussian Observes the American Civil War

Moxley Sorrel, Recollections of a Confederate Staff Officer

Jim Stempel, The Battle of Glendale

Arthur Wagner, Organisation and Tactics

SGP Ward, Wellington's Headquarters

Geoffrey Wawro, The Austro-Prussian War, The Franco-Prussian War

Copyright 2008-20, John Hamill

Back to Civil War Virtual Battlefield Tours