Charleston

June 28, 1776

In the summer of 1775, with their main army besieged at Boston, the

British began planning an expedition to the South, believing that a

show of force by regulars might encourage the Loyalists to rise up and

restore the crown to power. The overly optimistic plan, influenced

by the deposed Southern governors, envisioned bringing the four

Southern colonies back in line and allowing many of the British troops to

return north. On January 20th, 1776, Sir Henry Clinton set sail

from Boston with 1,200 to 1,500 men. They would sail to Cape

Fear off North Carolina and rendezous with a fleet under Peter

Parker escorting an expedition under General Cornwallis. After a stop

in New York harbor, Clinton arrived off Cape Fear on March 12th.

There he learned that his hoped for Loyalist support had

been defeated the day he left New

York Harbor, February 27th, at Moore's Creek Bridge, in a fight sometimes known as the 'Battle of Slippery Logs'.

Parker's ships with Cornwallis only started arriving on April

18th, and it was late May before the last ships arrived.

With the Loyalists crushed, the original British

plan was no longer workable, but perhaps something useful could

be done. Clinton suggested setting up posts in Virginia, but

Parker talked him into capturing Ft Sullivan protecting Charleston.

The fort was incomplete, and once it was

captured, it might be held with a small force.

The fort, since renamed Fort Moultrie after its

commander, held up to

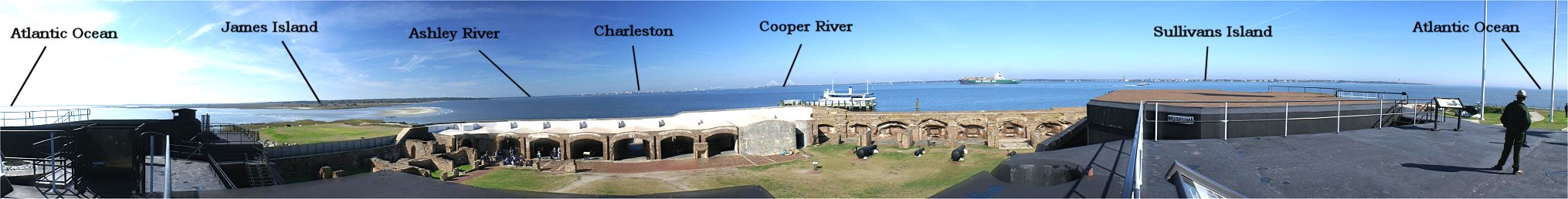

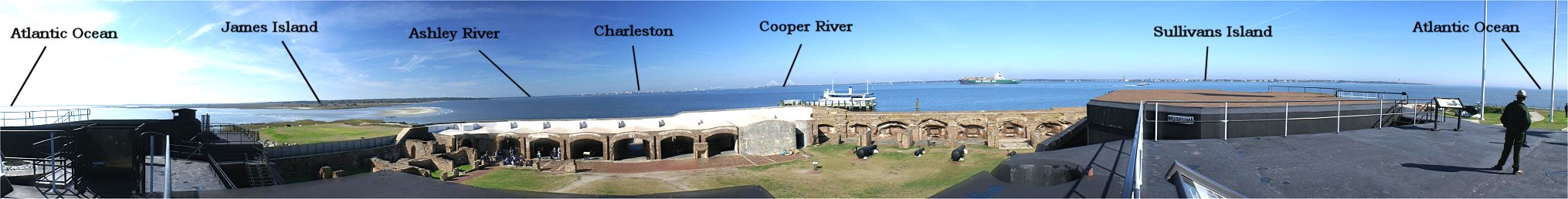

25 guns facing the entrance to Charleston harbor. Between

Sullivan's Island and James Island was a dangerous shoal.

(Ft Sumter would be built on it many years later.) A

small channel did exist between the shoal and James Island, but it was

too treacherous to use. Charles Lee, when he arrived to take

command of the American defenses, was not happy with the preparations

so far. The fort had little protection to its rear, with only

a seven foot tall wall and a few guns. With no bridge to the

mainland, there was easy way to retreat. Lee ordered a

floating bridge constructed, but the resulting structure was too weak

for the troops to use. Three miles east of the fort was

undefended Long Island, separated from Sullivan's Island by

Breach Inlet. Although Sullivan's Island at Breach Inlet was

defended, a British force

might use Long Island (now the Isle of Palms) as a springboard to the

mainland and isolate Fort Moultrie. This is exactly what

Clinton planned - eventually.

View From Ft Sumter, Then Shoals

Breach Inlet

On June 16th, Clinton landed roughly 2,500 men on

Long Island, visible at the other end of the modern bridge.

Trying to cross Breach Inlet in boats to Sullivan's Island, boats

would ground in a foot and a half of water, but when men would get out

to push, they would find the water to be seven feet deep. With

such uneven footing and with American troops defending the landing

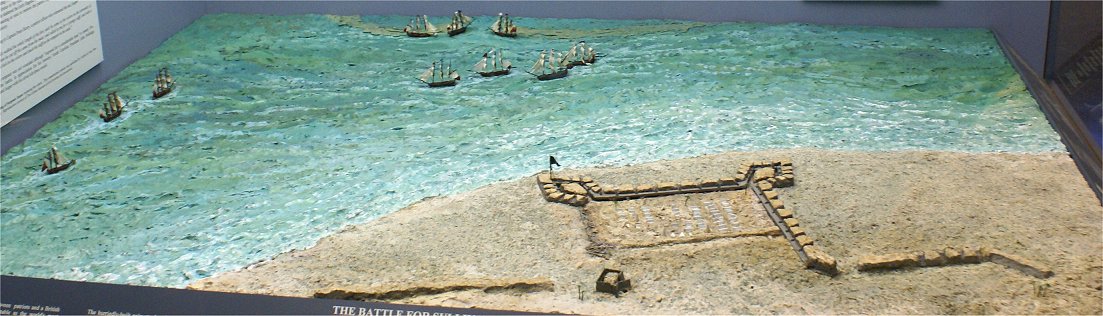

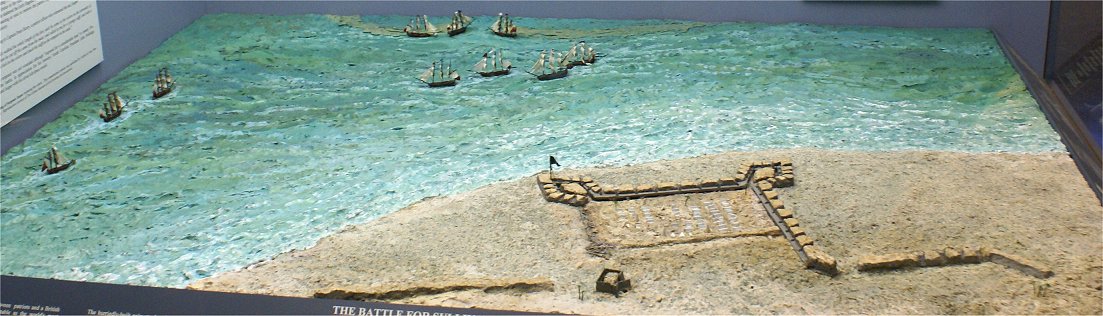

area, the crossing was called off. Parker felt that a naval

bombarment would neutralize the fort, and if he could get ships past

the fort, he could cover Clinton's troops as they crossed over to the

mainland to cut off retreat from Sullivan's Island.

Contrary winds pushed back Parker's attack until

late morning on June 28th, giving the Americans more time to prepare.

A bomb ketch started the bombardment with 10 inch mortars at a

mile and a half. Four ships approached to around 400 yards

and opened fire. They were joined by three ships in a second

line further behind. Around 100 guns fired on the fort for around

an hour. The British mortar bombs were generally absorbed in

swampy or sandy soil, and the cannon balls were absorbed by the sandy

soil behind the fort's palmetto walls, wich didn't splinter like other

woods. The three ships of the second line were to pass into the

harbor and around the fort, firing into its flank and rear and allowing

Clinton's men to cross to the mainland. All three ships ran

aground in the middle shoal, though, removing their guns from the fight

and preventing Clinton's crossing to the mainland. Essentially,

this sealed American victory. One of the grounded ships was

abandoned and destroyed while the other two were withdrawn

for repair.

During the bombardment, a British shot

shattered the flagpole, which fell outside the fort along with the

flag. The flag coming down was considered a sign of surrender, so

a Sgt. Jasper climbed the wall to the other side and erected the flag

again with an improvised pole.

Statue of Col. Moultrie in Charleston

The fighting ended at dark, with the British fleet

withdrawing with the tide. Col Moultrie and his men

had dished out significant punishment to the British fleet,

concentrating much of their fire on Parker's flagship, the Bristol,

which took 70 hits and lost 64 dead and 161 wounded. Parker

himself was slightly wounded. American losses were

relatively light, 10 killed and 22 wounded.

Clinton remained on Long Island for three

weeks, then withdrew with the fleet to New York City, where they

participated in Sir William Howe's campaign. The expedition had

been an embarrassing fiasco. The South remained fully in

patriot hands until Savannah was captured in the final days of 1778.

Charleston was captured only in the summer of 1780,

setting off fighting in both Carolinas and Virginia. Although

the South was spared for much of the war, ultimately the war would

be decided there.