Brunel's Sawmill

at the Chatham Dockyard

|

Sawpits, usually grouped together in rows,

and ideally covered by a roof, were the traditional method of sawing wood in

dockyards.

There is little trace of sawpits now, but in the early 1800s, 150 sawyers were

employed at Chatham, and sawpits were even beneath

the Clocktower Building. Despite his difficulties, the unlucky man in

the pit made less money than the man on top, whose skill kept the saw running in

a straight line. The sawyers, however, would become largely

unemployed. In the 1790s, Inspector General of Naval Works Samuel Bentham,

brother of famous economist Jeremy Bentham, became interested in the possible

use of steam power in the dockyards. At Portsmouth, a steam powered pump

for draining dry docks was installed, and a man named Marc Brunel built an impressive steam

powered block mills, making a long the time consuming process of

block making quick

and cheap.

|

Models of Sawyers and a Blockmaker |

Brunel, a French émigré opposed to the Revolution, had moved to

America, then to Britain. There, he would gain fame as one of the great

engineers in history, developing the technology to tunnel under the Thames.

(He also fathered Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who would surpass even his father's

engineering genius.) Having already saved the Chatham dockyard with his

steam powered dredger which kept the Medway open to ship traffic, he patented a

circular saw. He next set his sights on designing a steam powered saw

mill, and since Chatham was primarily a building yard, it was the logical place

for the new project, which would also feature a small version of his block mills

on the upper floor.

Impressive not merely for its fascinating process of transporting and sawing

the lumber, the new sawmill was also built using iron columns and prefabricated parts.

(Shown above right are numbered sections.) Problems developed when the

chimney began to settle during construction, and work was halted. Brunel

had iron ties put into the brickwork to help support it, probably another of his

many engineering firsts.

When the sawmill became operational, the finished product

was taken out of this end of the building, and with the help of gravity, it was

taken with relative ease to rest of yard.

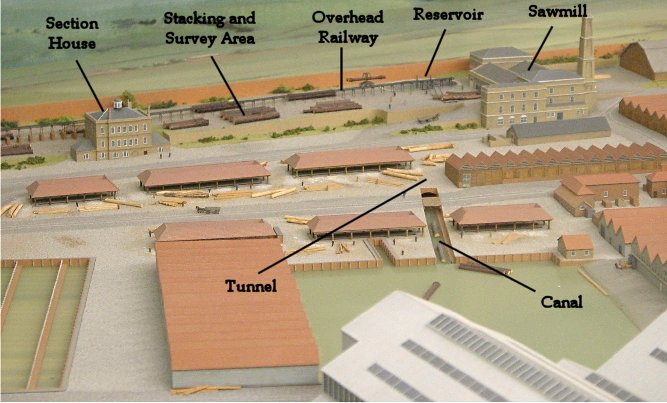

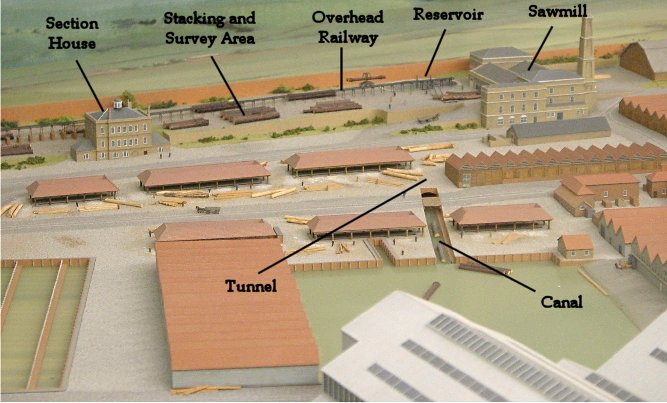

Getting A Log to the Sawmill - Model of 1850s Dockyard in Chatham Dockyard

Historical Society Museum

For the site of the mill, Brunel selected a hill outside the boundary of the

dockyard which was then purchased. This hill, 35 feet above the

surrounding land, was seen as a hindrance by others, but as we will see, was all part of

Brunel's ingenious design. Connected by tunnel with the Medway, the mast

pond would serve as a temporary storage area for logs floated in from the river.

With the construction of an additional 250 foot canal and a 300 foot tunnel, the

logs would then float from the mast pond into a reservoir next to the sawmill.

(In the model shown above, this reservoir is obscured behind the south end of the

overhead railway, another innovative feature of the design.)

Lifted by the weight of condensor water from the sawmill's steam engine,

a log was then picked up

by crane onto the overhead railway. Connected by a chain unrolled from

around a drum, and powered by the steam engine, the log was lowered down

the slope then dropped into one of the piles on either side of rails. In

this

stacking and survey area, the log dried and was categorized. When ready

for sawing, the log would be picked up and brought uphill, where it was dumped

conveniently at the sawmill door. With a minimum of human or animal labor,

the log was ready for sawing, and since the log hadn't been dragged along the

ground, there was no sand or gravel to complicate the sawing.

On the right of the picture are several of the surviving frames of the saws,

no longer used for their original purpose, of which there were originally eight along with two benches. These frames

held up to 36 saws each, although blades could be removed or added according to

the number of boards needed. The logs were pushed through the frames from right to left

by

windlasses and capstans, all powered by the 30

horsepower steam engine.

Numbers help explain the success and revolutionary nature

of the sawmill. Before, the dockyards employed 900 total sawyers, and of

that total, 150 worked in Chatham who were paid 11,000 pounds per year. Transport of logs around yard

had cost 4,000 pounds per year. Brunel

had estimated that his sawmill would require only 2,000 pounds per year for labor and maintenance.

The sawmill not only completely replaced the sawpits in Chatham, it could saw

enough for all of the dockyards. In later years, the sawmill fell out of

its intended use and became a laundry. In World War II, a command and

control bunker was dug nearby.

Acknowledgements: Although an important and impressive historical site,

the Brunel Sawmill is inexplicably not one of the dockyard tourist

attractions. I would like to thank North Kent Joinery Ltd., which occupies

the building, for allowing me access, and Brian Jenkins for arranging the visit.

Back to Chatham - The

Royal Dockyard