Chatham

The Royal Dockyard

From early on, the River Medway was a convenient location for maintaining warships. By beaching them on the mudflats at high tides, they could be serviced below the waterline. The river was also used for putting ships into "ordinary", or long term storage during peacetime. With the development of the state and the navy, more advanced shore facilities were needed, and the Medway area was a logical place for them. So around 1570 the Chatham Dockyard was founded, and it soon became Britain's largest and most important dockyard. Featuring mast ponds and a wharf, it was conveniently placed to service the fleet that repulsed the Armada, but it rose to its greatest prominence during the Dutch Wars of the mid 1600s, by which time it featured dry docks. A major disaster was narrowly averted in 1667, near the end of the Second Dutch War, when a Dutch raid nearly reached the dockyard, where much of the English fleet had been prematurely put into ordinary in order to save money.

Chatham declined in importance and became largely limited to ship building and long term ship maintenance because the eight mile journey up the twisting Medway was difficult in the age of sail. Begun in the 1660s, a newer yard at Sheerness at the mouth of the Medway largely took over the duties of simple maintenance and supply. The problems at Chatham only worsened as the river continued to silt up. Further, Britain increasingly saw France as its greatest threat, so the Portsmouth dockyard on the south coast grew in importance, and a whole new dockyard was constructed in Plymouth in the 1690s.

Mass production came to Chatham in the early 1800s. In 1814, Marc Brunel completed an impressive steam powered sawmill with an overhead railway. In the 1860s, the yard became the first government facility to construct an ironclad, the HMS Achilles, and a major expansion project updated Chatham to service the new steam navy. Despite this major Victorian expansion, the shallow waters of the Medway would never be suitable for the larger warships of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, so the yard began to specialize in submarines and cruisers. In 1984 the dockyard closed, but it is now an excellent tourist attraction, which, along with the area's many other historical sites, is able to entertain a history buff for several days.

This model in the Chatham Dockyard Historical Society Museum shows the yard as it would have appeared in the 1850s, which is much as it appears today. Seven covered slipways and four dry docks dominated the riverfront. Slipways were used for ship construction, and although the dry docks were used for major repairs, they were also used for construction of the largest warships. As we will see, most of the dockyard's many buildings in some way contributed toward the building and repair of ships. A sheerhulk, an old warship modified as a crane, is shown here moored in the river in order to install masts.

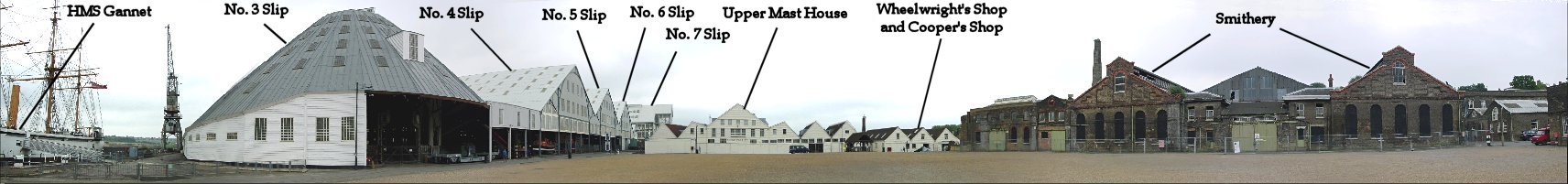

Panoramic View From Near No. 3 Slip

In this and the following panoramas, we will see the center of the Georgian dockyard shipbuilding area. Here, items would be made, stored, and taken to the slipways and dry docks for assembly.

On the far left, No. 4 Dry-dock now holds the 1878 steam and sail powered warship HMS Gannet. Next are the prominent Covered Slipways, Numbers 3 through 7, where ships were built and launched. No. 3 is oldest, and is wooden, while the rest are made of steel. The Mast House, dating to 1758, is next. Wood from a mast pond on the opposite side of the building was brought inside and worked into masts. On the upper floor, called the mould loft, full sized cross-sections of ships were drawn and wooden templates were made to assist in the building of a particular ship. Many of the dockyard's wooden buildings are made of re-used wood from warships, and a number of ships' timbers have recently been found under the floor of the Wheelwright's Shop further right. No. 1 Smithery, dating originally to 1808, was where metal items were made for ships; it is the large complex of buildings on the right half of the picture. A No. 2 Smithery, which has since been destroyed, occupied much of the open area in front of No. 1 Smithery.

Panoramic View From Near No. 4 Slip

|

|

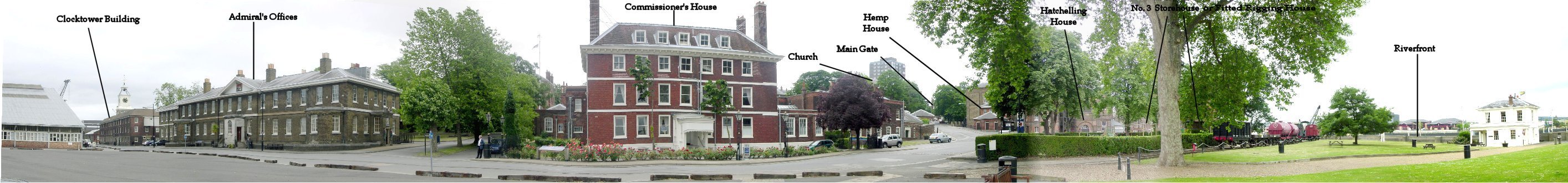

Panoramic View Near Site of Nos. 1 and 2 Slips

This panorama, taken further south near the former site of two slipways, shows a number of important buildings. The Clocktower Building, completed in 1723, is the oldest storehouse in Britain, used to keep ship building materials conveniently near the slipways and dry docks. A mold loft on the top floor was used for drawing cross-sections of ships. The far end of the building once had sawpits underneath that have since been filled in. The Admiral's Offices are next, and between the Admiral's Offices and the next building is the very nice man, Brian Jenkins, who showed me around the dockyard. He is seen here patiently waiting for me to slowly complete the panorama.

The Commissioner's House, the oldest naval building in country, was built in 1703 on the site of a previous commissioner's house - this at the urging of none other than the new commissioner himself, a man who obviously felt entitled to a large and impressive house at government expense. He must also have felt entitled to a short walk to work, because the building is located in the heart of the yard, essentially in the way of everything else. Inside the building is an impressive ceiling painting. The prominent road continues up the hill to the main gate and church. On the right of the picture can be seen the Hemp House and the Hatchelling House, which are part of the Ropery. Further right, barely visible and obscured by trees, is the end of the old Fitted Rigging House, built as No. 3 Storehouse in the late 1700s.

Northern End of the Georgian Dockyards Looking South - Old Mast Pond Area

This view is back on the other end of the yard, to the north of previous views. The high roofed buildings in the center and right of the picture are riverside slipways that were covered beginning in the early 1800s in order to protect ships under construction. This was done at the urging of Samuel Bentham, the brother of the economist Jeremy, who saw covered slipways during a trip to Sweden. Not visible, drydocks are beyond the slipways. The white building in the center is the Upper Mast House, and the vast modern parking area in front of it was occupied by mast ponds in the 1700s. Before they were prepared, the tall pine or fir timbers used for masts were kept in the ponds, potentially for decades, so they wouldn't become brittle and easily breakable as the resin dried. Brick arches kept the masts completely submerged in lime-treated water which prevented creatures from damaging the wood.

Buildings - Georgian Era to 1850s

Expansion Plans and the Victorian Dockyard

Early 19th Century to Victorian

Acknowledgements: Many thanks are due to Brian E. Jenkins and of the Chatham Dockyards Historical Society who helped the webmaster by providing access to, and information about, some of the facility's buildings. Any errors, of course, are the webmaster's.

Links

http://www.chdt.org.uk/NetsiteCMS.php The Historic Dockyard, Chatham - includes info on buildings

http://www.dockmus.ik.com/ Chatham Dockyard Historical Society

http://www.hants.gov.uk/navaldockyard/ Naval Dockyards Society