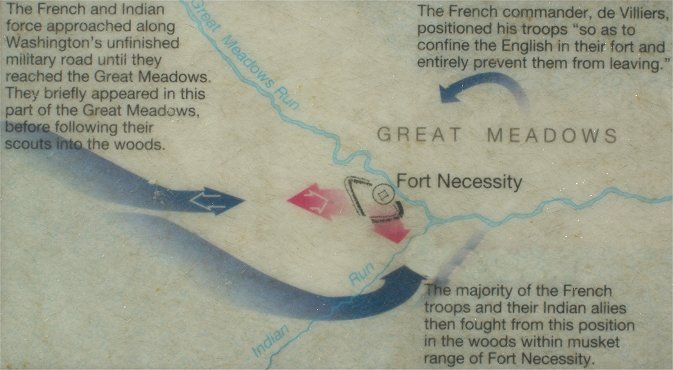

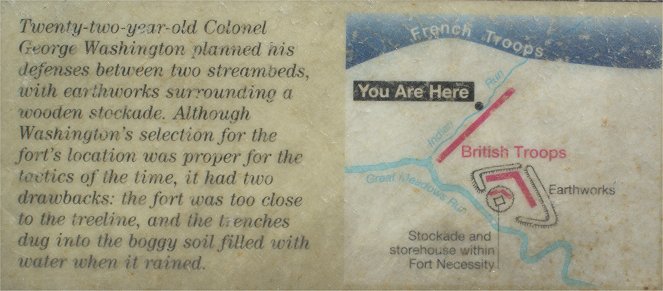

Washington started building a 'fort of necessity' at a place called Great Meadows, a clearing in the forest.

When he heard that a small French force had been dispatched from Ft

Duquesne and was advancing toward him, Washington marched to meet it.

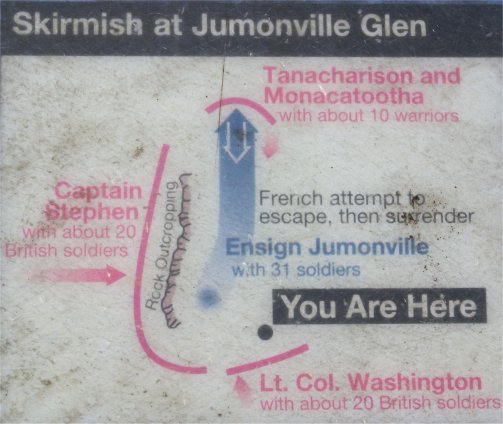

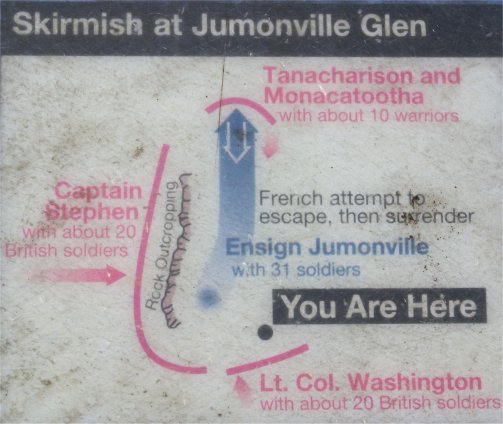

On the morning of May 28, 1754, Washington located the French

force camped half a mile off the established trail in a hollow below a

rock outcrop. Washington kept about 20 men atop the rocks under Adam

Stephen and took another twenty off to the right to flank the French

camp. A party of roughly a dozen Indians were sent to the French right

flank. When one of the French troops detected the British troops, he

sounded the alarm, and the French rushed to the muskets. Washington

ordered his men to open fire. After a fight of no more than 15

minutes, the French surrendered, except for one man who escaped to Fort

Duquesne. Washington't force lost one killed and two wounded. The

French party lost 10 killed and 21 captured.

There are few accounts of this controversial incident, and they do not

always correspond. The commander of the French party, Cpt. Jumonville,

was killed in the fight. Some accounts say that he read a diplomatic

letter at the beginning of the fight. Other accounts, including from a

French participant, make no mention. Washington himself denied that it

happened. We can only make an educated guess at the truth. The facts

that Jumonville had been away from Ft Duquesne for several days and was

camping in a remote location suggests that his mission was not wholely

diplomatic. A good argument can be made that Jumonville was given the

option to either use military force if he had the advantage or to

attempt diplomacy if he was weaker. The French called the event an assassination and used it for propoganda

purposes. |

|