Portsmouth

The Royal Dockyard and the Gunwharf

Henry VII established a dockyard on the south coast at Portsmouth by in the 1490. It featured the world's first dry dock. At the time European monarchs were reforming government, forming standing armies, and starting the development of standing navies. The early warships built by Henry VII were secondarily intended for the wool trade, but Henry VIII had warships built solely for war, and they required bases for maintenance, rebuilding, and resupply. Although Chatham near the mouth of the Thames gained importance in the Dutch Wars of the mid 1600s, Portsmouth became the most important dockyard by the 1700s, when France was the undisputed greatest threat to Britain.

View From Spinnaker Tower Courtesy of Bill Kennington

From several hundred feet up, you can get a good idea of the layout of the Georgian-era dockyard.

The Gate

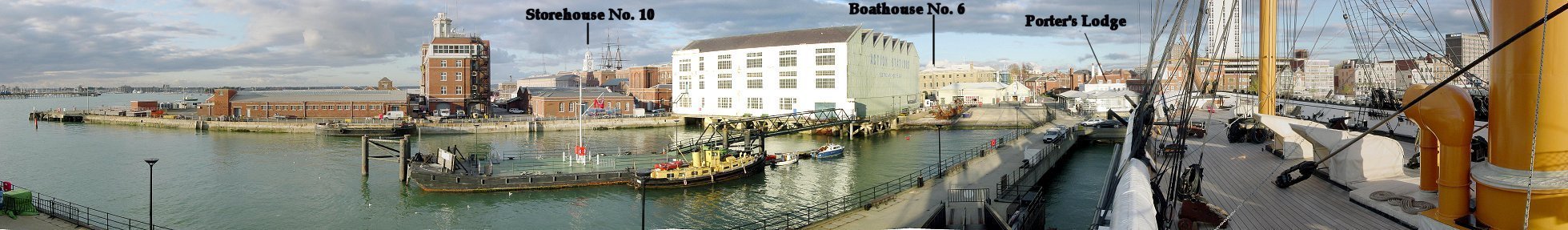

From HMS Warrior

The masts on the left-center of the picture belong to the HMS Victory. The long buildings below and to their left include Storehouses 10 and 11 which now house the Royal Naval Museum. They were built between 1764 and 1784 on the waterfront. The more modern buildings to their left are separated by a channel and are on reclaimed land. The Georgian buildings in this area do not survive, but were also storehouses. The storehouses held miscellaneous spare parts for ships which were collected by boats and taken to their home ships just outside the harbor in the Spithead. A series of cranes were used to load the boats.

In Georgian times, a mast pond with mast houses were in the area to the right of the storehouses. The mast pond complex extended through the area of the prominent white building with "Action Stations" on the side to the edge of the dockyards, approximately marked by the Porter's Lodge. Another mast pond still exists to some extent in front of Boathouse No. 6. Mast ponds were used to submerge timber for ships' masts so that it wouldn't become brittle as the resin dried.

The relatively small white building just to the left of the Warrior is near Victory Gate, completed in 1711. This is where tourists now enter the dockyard attractions. The City of Portsmouth is visible off the starboard side of Warrior. If you walk straight through the entrance you will pass Porter's Lodge, the Mastpond, and Boathouse No. 6 then past the storehouses to HMS Victory.

Zoom View of Storehouse From HMS Warrior

The clock on Storehouse No. 10 was destroyed by bombing in World War II but was restored in the 1990s. The earliest storehouses were made of wood and susceptible to fire. Later brick storehouses were safer but contained small cramped rooms which were awkward when bringing in items or taking them out. These late 18th century buildings were spacious, with three stories, including an underground cellar for storing flammable liquids. In the 1700s, storehouses often used moveable wooden partitions instead of permanent rooms, and cranes and a wooden rail transport system helped get items in and out of buildings.

Original Floor

Porter's Lodge

Near Victory Gate, dating to 1708, is the Porter's Lodge, the the white building shown here. The porter's job was to mark working hours by ringing a bell, guard the premises, and prevent employee theft, a serious problem in the Georgian era. Georgian era employees were poorly paid but tried tried to make up for it through theft. In fact, the town near Sheerness dockyard was called Bluetown because employees almost universally used stolen blue paint on their houses. The brick wall around Portsmouth dockyard replaced a wooden palisade which was easily pierced by thieves.

Boathouse No. 6 and the Mastpond

The Mastpond dates to 1665, when it was dug by Dutch prisoners of war. Because the Portsmouth dockyard evolved over time instead of being designed and built at one time, everything wasn't always placed efficiently. The mastpond is a good example, being relatively far away from where ships were built and maintained. Boathouse No. 6 dates to 1846 but is much like 18th century boathouses. There were also boathouses on the left and right of the mastpond.

Naval Academy and Storehouses

The prominent building on the left half of the picture is the Old Naval Academy, which dates to 1733. Behind the Naval Academy is Storehouse 18, or the ropehouse, where rope was made. During the American Revolution an employee sympathetic to the American cause tried to burn down the ropehouse and the whole dockyard, but he succeeded mostly in getting himself hanged. Like the mastpond, the ropery was placed in a less than ideal place. It is too close to where ships were built and maintained, and its long length hindered movement around the dockyard. Problems like this are the predictable result of the growth of the facility over many years.

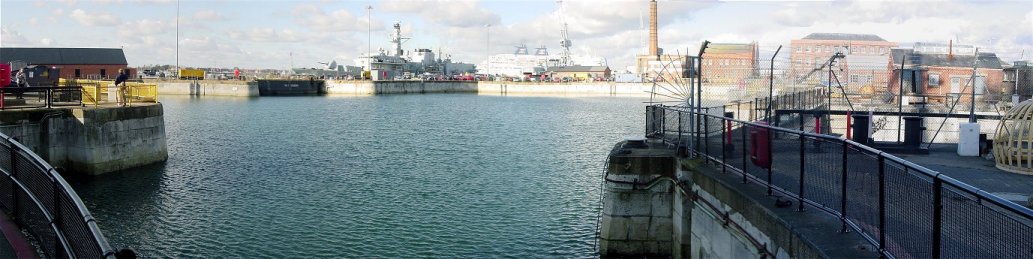

Ship Basin No. 1

After a ship was launched from a slipway or dry dock, it required fitting out, including the installation of masts. This could be done in a ship basin, or wet dock, like this one - Ship Basin No. 1, built in 1698, or elsewhere. Work on the above water portion of the ship was conducted in the basin, and not in the drydocks, so that they could be used for constructing or repairing additional ships. Another function of the basin was to store unused warships, putting them in ordinary, or in mothballs in modern terms.

Between 1780 and 1805 the basin was extended and more dry docks were added, to make a total of four connected to it. The narrow walkway at the right quarter of the picture is over the entrance to Dock No. 2, which now holds HMS Victory. Beyond it is Dock No. 3 which now holds the preserved remains of Henry VIII's ship the Mary Rose. Beyond, but not visible, are Docks 4 and 5. The dark gray caisson visible just below the bow of the modern ship is the entrance into the basin from Portsmouth Harbor.

Dry docks were a vital contribution to a fleet, and dockyards were only placed in locations where drydocks could be built. The original dry docks worked by piling up a mud wall to keep out the sea. This crude method was replaced by timber, then in the late 1600s - by stone. Ships could enter and exit the drydock only at springtides every two weeks. Water was originally pumped in and out of the docks by hand pumps. Horse powered pumps replaced them, which in turn were replaced by steam power. Cleaning, repairs, and maintenance below the waterline were much easier with a dry dock. The alternative, careening, involved dragging a ship into shallow water and turning it over on its side - not a good system. With regular maintenance in a dry dock, a ship could last fifty years, which more than made up for the time, effort, and expense to build the docks. Further, the largest warships couldn't be built on a slipway, only in a dry dock.

Dock No. 1 with Monitor M33 of the First World War

You can see on this picture, and the next one, that in addition to the steps along the sides of the drydock, there are smooth ramps which simplified lowering working materials and parts.

Dock No. 2 with HMS Victory

You can barely make out the copper plates covering Victory's bottom. They were an innovation introduced during the American Revolution which protected and preserved the wood. Further, mollusks and other sea creatures would not live on copper, so the hull would not become fouled. So even though coppering was expensive, it was well worth the cost.

HMS Victory

Construction began at the Chatham dockyard in 1759, but the ship wasn't ready for action until 1778. Victory was found to be an excellent design and was used as a flagship by Adm. Nelson, who was killed in the decisive battle of Trafalgar. The figurehead is a reproduction of the one used at the battle.

Wider View of Basin No. 1

Here is a view of the basin area from further away. The boat in the lower foreground, Monitor M33 of the First World War, is in Dock No. 1, and you can see the stern of Victory in Dock No. 2. Starting in the late 1700s, water was pumped out of the docks by steam powered pumps. Maps show that the small brick building with the green roof in the center of the picture is the Pumping Station.

To the right of the Pumping Station, the two rectangular buildings are the Block Mills, which date to 1802. They were built over a basin and are joined together by a one story building containing a steam engine which powered both the block mills and the pumps. The mills used Marc Brunel's revolutionary steam powered machines for making blocks, the wooden parts used to make the labor saving pulleys in ships' rigging. The machines made producing identical blocks quick and easy using machine tools with a fraction of the labor of the old ways. Specifically, 10 people replaced 110!

Not visible, the 19th Century Steam Basin No. 2 is behind the Block Mills. Beyond it is Fitting Out Basin No. 3, and I suspect the cranes in the distance on the right half of the picture are around Rigging Basin No. 4 and Repairing Basin No. 5. This massive expansion of the dockyard starting in the mid 1800s was to deal with the larger and more complex steam ships, but this area is closed to the public.

The view looking west from here shows the Royal Clarence Victualling Yard.

|

|

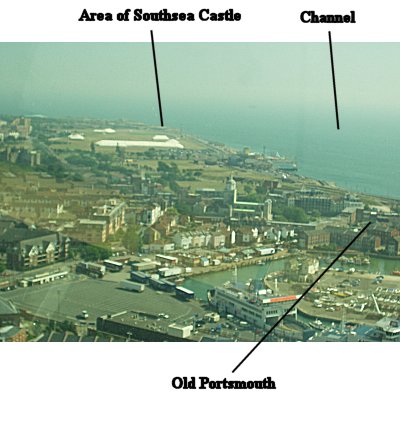

View From Spinnaker Tower Courtesy of Bill Kennington

On the left you can see part of the dockyard, areas like the Naval Academy Building (not the one near Victory), the Ropery, the Commissioner's House, and the church, which are not open to the public. The town of Portsea sprang up next to the dockyard, and it, along with the dockyard and the nearby ordnance facilities, were protected by fortifications. Part of the Gunwharf area is visible on the right half of the panorama. Like the dockyard, much of the Gunwharf was built on reclaimed land. Here, weapons and ammunition were stored and transported to and from ships. The recently built canal marks the location of a creek which centuries ago featured a mill that supplied food to the navy. Now it roughly marks the boundary of the old Gunwharf on the left and new Gunwharf on the right. The Vulcan building, built between 1811 and 1814, was the main ordnance storehouse. Beeston Bastion, part of Portsea's defenses, was behind the Vulcan building, but these close-in defenses were razed when the Palmerston forts were built on the heights several miles to the north in the mid 1800s.

Now few ordnance buildings remain, and a massive new development, including Spinnaker Tower, occupies formerly Ministry of Defense land, known as HMS Vernon since the early 1920s, when it was named after a ship used for the same purposes. The rightmost picture doesn't quite overlap, but you can see the English Channel and the location of old Portsmouth at the southwest tip of the peninsula. Gunpowder was stored in one of the medieval towers defending Portsmouth, but fear of an explosion lead in the 1770s to construction of a magazine at Priddy's Hard near Gosport. Langstone Harbour is the eastern boundary of the peninsula while the dockyard occupies the western side.

Old Gateway Behind the Vulcan Building

Grand Storehouse or the Vulcan Building

| Built between 1811 and 1814, this was the main storehouse of

the ordnance facility and Royal Ordnance's largest building. You can see that the brick on the wing on the

left and on the clocktower do not match the rest of the building.

These are recent additions to restore the building to its appearance prior

to the Nazi bombing. Like many of the buildings which stood on this

ground, this one gets its name from a ship, HMS Vulcan.

The photo on the right is looking in the opposite direction toward the water. Stacks of cannonballs give some idea how the area was once used. |

|

Gunwharf Infirmary

Inside the Marine Barracks in Portsmouth Courtesy of Bill Kennington