The Seven Days

June 25 to July 1, 1862

With failures in attempts to advance directly on Richmond at First Manassas and Ball's Bluff, the Union decided on a new approach. In April 1862, Gen. George Brinton McClellan moved his Army of the Potomac to Fortress Monroe to advance toward Richmond up the Peninsula between the York and James Rivers. Moving slowly up the Peninsula, McClellan was near the outskirts of Richmond by late May 1862. McClellan's supply line was a rail line from White House due east of his army. The rail line crossed the Chickahominy River on its way to Richmond, so McClellan believed that he had to defend both sides of the Chickahominy River. The Confederates saw the vulnerability of McClellan's army, and Joseph Johnston attacked with his Confederate army on May 31st. Despite the great potential of the attack, it was bungled, and Johnston was wounded. McClellan's army remained outside of Richmond as Union armies in the west were advancing. Thoughtful Confederates could envision a short and dim future for their new nation.

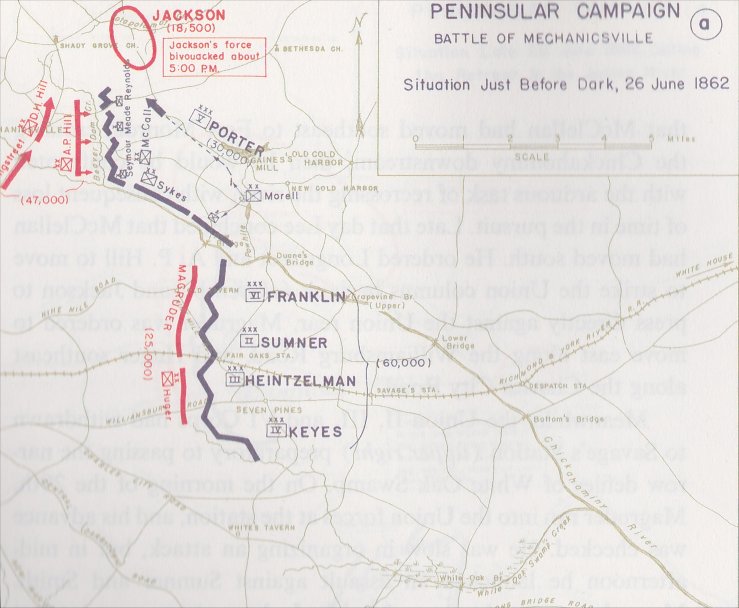

On the morning June 26th, Lee observed the crossing of the Chickahominy River by three divisions from here, an earthwork built for the defense of Richmond that overlooks the broad, swampy valley below. Waiting to cross for word from Jackson, A.P. Hill heard nothing and decided to cross his division anyway. D.H. Hill and Longstreet followed.

Beaver Dam Creek

| With three

of his divisions north of the Chickahominy against the isolated Union V

Corps,

Lee had left only two divisions south of the river to hold off most of

McClellan's

army. Jackson was to join Lee north of the river directly from

the

Valley, but he was uncharacteristically late. A.P.

Hill cleared

Mechanicsville on time expecting

that Jackson would turn the Yankees out of their formidable position

behind

Beaver Dam Creek. Lee had crossed the Chickahominy and was while

conferring with A.P. Hill, he was visited by Jefferson Davis.

Concerned that McClellan might snatch the iniatitive

and attack the vastly outnumbers Confederates south of the

Chickahominy - or mass against Jackson - Lee ordered A.P. Hill to

attack. An attack would also serve to pin the Federals in

position, making them vulnerable to Jackson's planned maneuver around

their flank. At the time of the battle, the slopes on the left of the panorama were bare, not wooded, and they were occupied by Yankee artillery atop the hill (14 guns) and infantrymen in tiers of riflepits. The foot bridge obscured behind some trees on the right of the panorama was the location of the road bridge which crossed the creek, then passed Ellerson's Mill. The creek was dammed to run Ellerson's Mill. The near, Confederate, side of the creek was bare except for a small group of woods at the creek. Pender's brigade had already attacked. After feeling out the position, it was decided that Ripley's brigade would move against the Union left near the Chickahominy and hopefully move around the Union left flank. The ground was not inspected and the resulting attack fell well short of the Union flank and struck here at the pond of Ellerson's Mill. The Confederate brigade was raked as it moved diagonally to the flank. The attack was a complete and costly failure. Although some men entered the creek, the brigade largely went to ground near the creek bank and remained there until dark. Confederate casualties on the day approached 1,500 compared to only 361 Federals. Jackson had never entered the fight, and Lee had not reached New Bridge, where he hoped to gain a more direction connection with Magruder and Huger south of the Chickahominy. On orders from McClellan, Porter withdrew to a position south of Gaines's Mill and New Cold Harbor early on the next day. McClellan decided to 'change base' to the James River, and Porter taking a stand south of Gaines's Mill would buy time to evacuate the White House base. |

West Point Atlas of American Wars 1689-1900 |

Gaines Mill

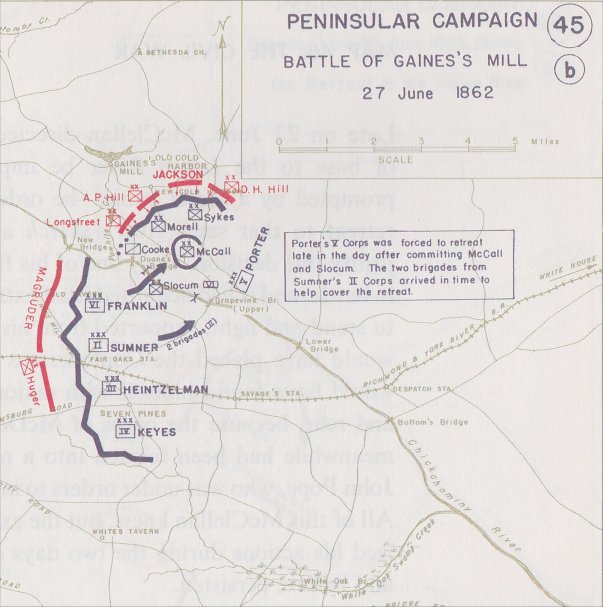

By 2 P.M. on June 27th, Lee was attacking Porter's corps near Gaines Mill. This is the creek at the foot of the hill defended by Porter's V Corps. Attacking Confederate troops advanced toward the swampy Boatswains Creek off the picture to the left with the objective of capturing the hill to the right. The Yankees were entrenched in three lines on the slope in a sparse woods. The land to their front at the time was cleared with no cover except for near the creek itself. Confederate troops went to ground, unwilling to go forward or fall back. On the rebel left, Jackson's planned turning movement had gotten lost and attacked the Union center.

Hood's Brigade

Late in the day, Lee's first major battle as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia was looking like a defeat. At 7pm, he committed Whiting's Division. Hood's Texas brigade was part of the division. Lee asked Hood if he could take the heights. Hood responded, "I will try." Previous attacks had failed because the men had stopped to fire. Hood ordered his men to advance with the bayonet without stopping to fire. Near here, the Texans swept over their prone comrades, the men from previous attacks who had gone to ground, and they advanced into the Union position. It was a breakthrough!

Watts House

| Hood's brigade had smashed through the Union defenses on the wooded slopes on either side of this 360 degree panorama. Now they were atop the hill near the Watts House, shown here. The action continued into the area not preserved by the national park. The advancing brigade, led by the 4th Texas and 18th Georgia, captured 14 of the 18 guns of Weedon's Artillery in the field beyond. A desperate charge by 250 men of the 5th US Cavalry was repulsed with only 100 survivors. The Texas brigade lost 571 men but had won the day. Porter was forced south of the Chickahominy and McClellan decided to retreat with his whole army to Harrison's Landing. |  |

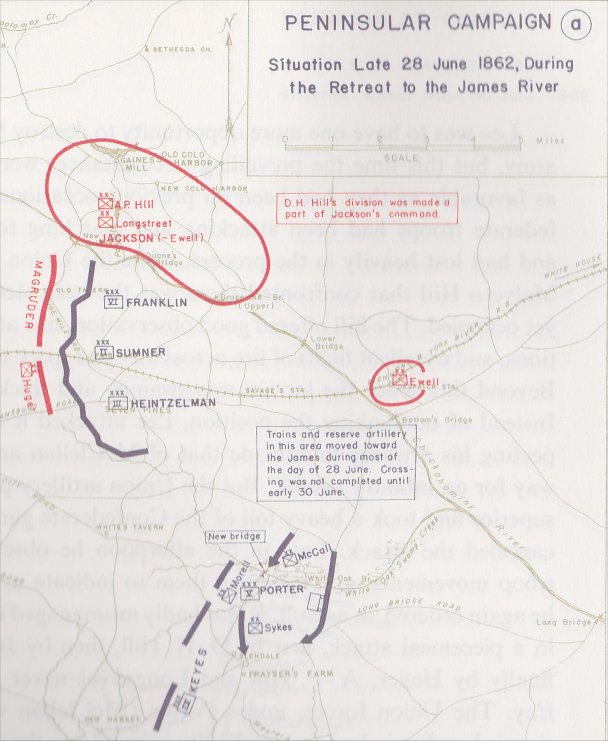

June 28, 1862 |

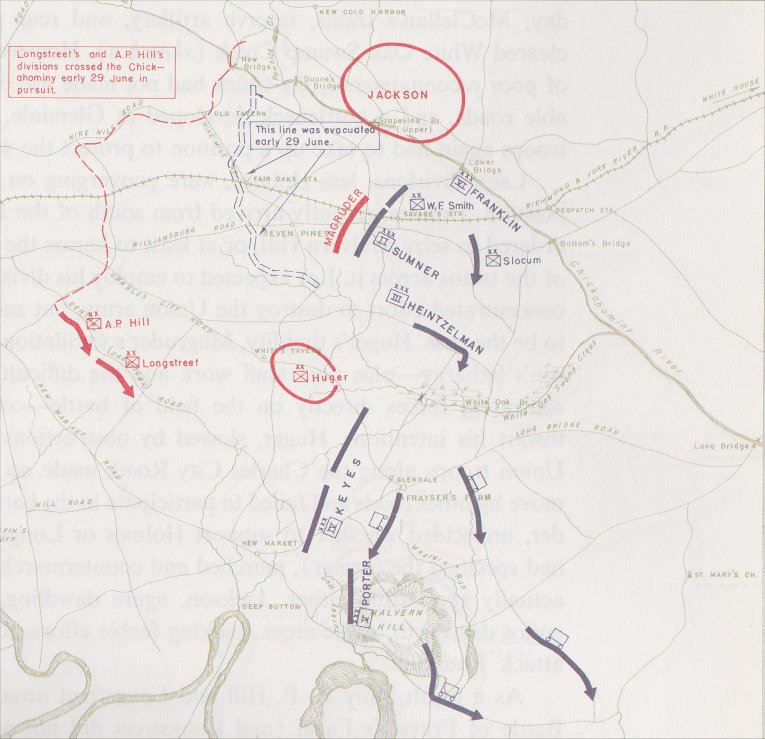

June 29, 1862 |

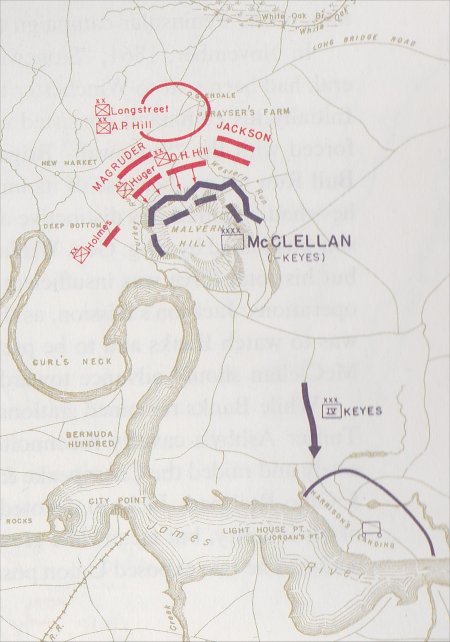

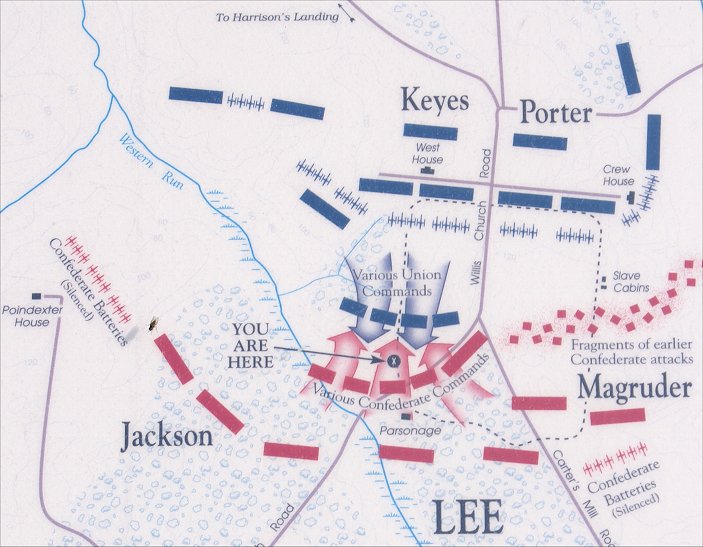

The simplified map above shows the situation on July 1st. With marshy Turkey Run dominated by Union artillery, McClellan's left flank was secure from Holmes. Union artillery was massed on Malvern Hill, with good fields of fire in all directions. Lee, however, believed he could destroy McClellan's army at Malvern Hill, and he saw this as his last chance to do so before McClellan escaped. To attack the hill, Lee had to silence the Union artillery. Confederate artillery emerged from both Confederate flanks to duel their Union counterparts, but they were silenced soon afterward. Confederate infantry was to attack only after the Union artillery had been silenced. One brigade, however, moved forward due to its own local circumstances. They cheered, which was the signal for the army to begin the attack. The other brigades interpreted it as such and advanced up Malvern Hill. Lee, meanwhile, had been scouting a potential move around the Union right flank. Returning to find his men attacking, he ordered them to continue. The Confederate attack was repulsed with heavy losses, about 5,000 men, and no gains. Union losses were also high, around 3,000, demonstrating that the battle was not as one sided as it is often portrayed. McClellan continued the retreat to Harrison's Landing the next day.

Confederate Artillery

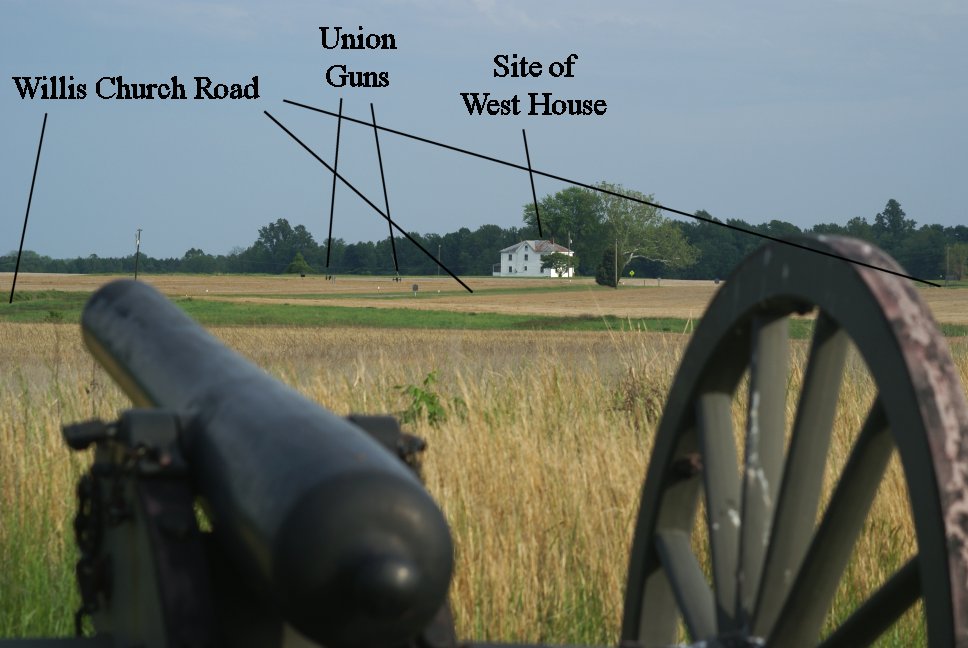

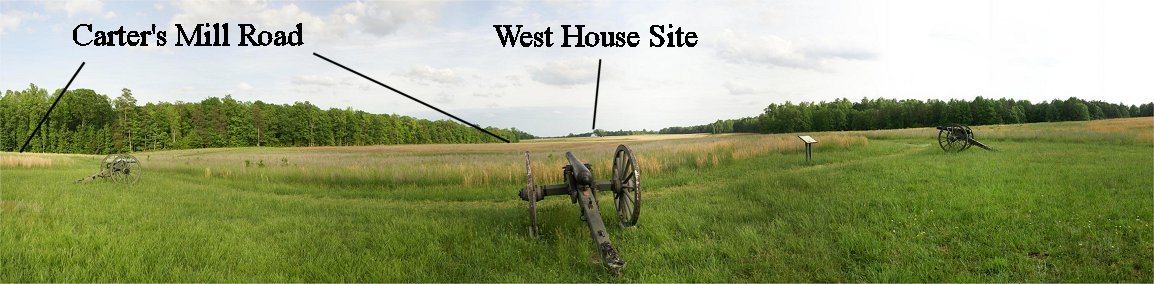

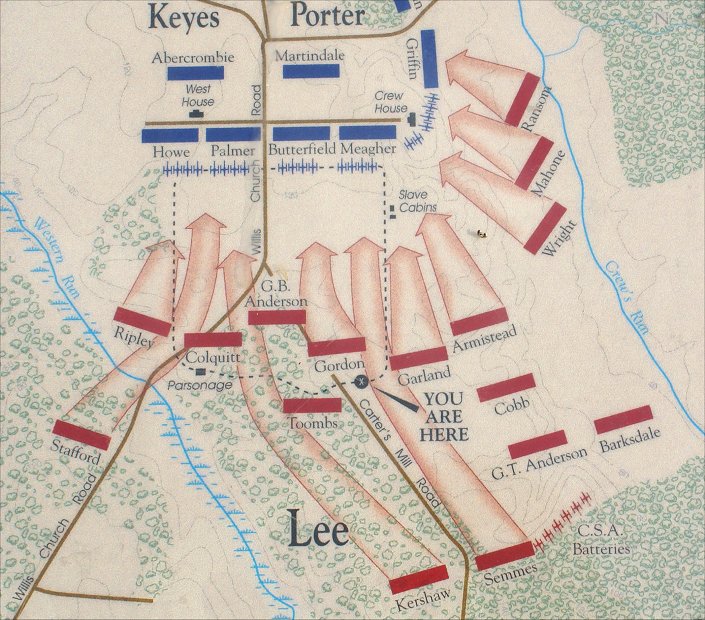

Approaching along Carter's Mill Road, this is where the Confederate artillery on Lee's right flank entered the action facing Union artillery already in position on either side of the West House. As the Confederates entered the field, they faced the concentrated fury of the Union guns. With less space available to deploy, the Confederate could get few guns into action; further, it was difficult to coordinate the deployment with the Confederate gunners on the left flank for the intended converging bombardment. The Confederate gun on the left flank entered the action afterward and were also silenced. For a successful infantry assault, Lee had to gain superiority in an artillery duel, but the Confederate batteries were silenced on both flanks.

| With the Confederate bombardment

stymied,

Lee began investigating a potential turning movement to the east,

something which he learned was impractical. The orders that

he

had given for an infantry assault were only after successful

artillery duel, so in his mind the orders were now dated and not in

force. Some of his subordinates, however, did believe they were

still in force, with the signal for the beginning of

the attack being cheering. It wasn't a sophisticated system by

any means, and the campaign showed bad staff work on many occasions.

When a portion of the Confederate infantry under Armistead gained

a

small, local success against Berdan's Sharpshooters, they cheered.

Magruder launched the rest of his division in an attack, and his

neighbor, D.H. Hill, followed suit. Gordon's

Brigade attacked in this area, eventually supported by Semmes's

Brigade. This attack directly toward the Union gun line reached

some slave cabins that were on the right side of the panorama, but

Union artillery

stopped the Confederate attack. On the right of the panorama there are some trees. They didn't exist at the time of the battle, but they will remain in place due to government environmental regulation. These modern woods cover a slope that descends to Crew's Run or Turkey Run, and several Confederate brigades attacked along these slopes and into the Union flank near the Crew House. |

Ignore "You are Here". |

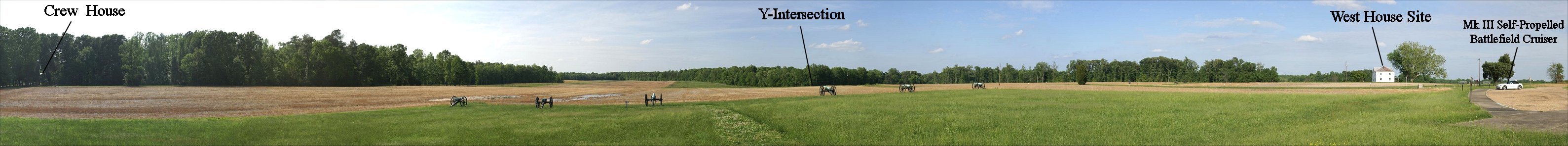

| The panorama above shows the type of slope that the western side of Malvern Hill had. Not wooded during the war, fields of fire were generally open, but undulations, or hollows, gave some protection to the Confederate troops as they advanced along the side of Malvern Hill, although this is not obvious now with all of the trees. Union guns near the Crew House stopped the Confederate attack in this vicinity, but the Confederates got close enough for small arms fire on the gun crews. The original Crew House survives, but it is a private residence outside of park boundaries. |  |

| Here you can see where the slope of Malvern Hill gets steeper. The West House is partially obscured, and by direct fire the Union guns could not reach much of the area between where the photo was taken and the Willis Church Road. After the Confederate infantry assault was repulsed, Union infantry advanced from the West House toward the Parsonage and engaged their Confederate counterparts. The fighting was indecisive and ended with nightfall. |  |

Berkley Plantation

| The Union army halted and camped at Harrison's Landing on the James River. Although Jeb Stuart fired a few artillery rounds into the camp from Evelington Heights, Lee considered the area too easily defended to attack it. The place was already historic by any definition. It had witnessed the first Thanksgiving in 1619, was home to America's first whiskey distillery, was home to a colonial shipyard, and was the ancestral home of William Henry Harrison. In the Civil War, this history was added to when "Taps" was written there. Lincoln also visited McClellan here twice to confer on strategy. |  Jeb Stuart's cannonball - allegedly |

What now, with the Union Army encamped on the James? The Union Navy dominated the river. McClellan might have moved on Petersburg just as Grant would do two years later, potentially turning the tables on Lee and cutting the rail link south. He did not.

Lee had saved Richmond but at great cost. In truth, he had had little alternative but to attack McClellan. His strategic position was improved, but it was still far from rosy. What would McClellan do now? And a new army of 'those people' under 'the miscreant' Pope was forming in Northern Virginia. To deal with it, Lee shifted Jackson's force north, where they clashed with the Yankees at Cedar Mountain. Lee then accompanied much of the rest of the army under Longstreet north to join Jackson, taking with him the subordinates that had performed best. Lee struck again at Second Manassas, hoping to smash Pope's army before McClellan's army transitioned north by water to join it. Another victory might change the course of the war.

Copyright 2009-14, John Hamill

Back to Civil War Virtual Battlefield Tours