Yorktown

August 20 to October 17, 1781

After Cornwallis's costly victory at Guilford Courthouse, North Carolina in March 1781, the British army in the South withdrew to the safety of Wilmington on the coast. Greene seized the opportunity and attacked British posts in the Carolinas. Cornwallis advanced into Virginia, vainly hoping that Greene's American army would follow - or that his efforts in the Old Dominion would ruin Greene. Cornwallis joined other British forces in Virginia and thoroughly raided the state with little opposition from the outnumbered American army under Lafayette, although clashes did occur at Spencer's Tavern and Green Spring, among other places.

Lafayette's French compatriot, Rochambeau, joined Washington's army outside New York City with a French army of his own. Washington was planning to attack the vital British base there. Some historians see this as a diversion, or an effort to gain more support for his army, but perhaps it was a genuine goal of Washington. Instead, at the urging of Rochambeau, Washington decided to move the combined army to Virginia, 450 miles away, and strike Cornwallis. The French navy under DeGrasse could stay in the North Atlantic until the end of October when the Caribbean hurricane season ended, and so the French admiral sailed to the Chesapeake Bay to prevent any escape or rescue of Cornwallis's army by sea. On August 20th, Washington and Rochambeau began the long journey from New York to Virginia. DeGrasse defeated a British fleet in the Battle of the Capes on September 5th, blocking a British escape by sea.

View From Yorktown Bluffs to Gloucester Point

|

Old Point Comfort, the site of modern Fort Monroe, had been suggested as a base to Cornwallis by Sir Henry Clinton, his superior in New York. The site was swampy and did not dominate the mouth of the James River, so Cornwallis opted instead for the second suggested location for a base, Yorktown, on the James-York Peninsula, which he occupied on August 1st. Near the mouth of the York River, it was a decent naval base. Since the river was constricted to the width of half a mile, cannon on the bluffs, where the panorama above was taken at the modern Victory Monument, and also on bluffs further upstream, and from Gloucester Point on the opposite shore, made it costly for an enemy navy to approach the town or pass upriver. The threat of fire-ships in the river also made any potential French move up the river costly. Throughout the coming siege, the allies worried that Cornwallis might cross the river and break through allied lines on Gloucester Point or escape upriver. Despite pleas to do so, the French admiral refused to send ships upriver, probably for good reason.

|

Aerial Photo is courtesy of Tim Timmons. From upstream you can see the narrow defensible area at the bridge, with Gloucester Point on the left side and Yorktown on the right. The river widens below Yorktown and empties into the Chesapeake. |

College Creek on the James

Washington arrived in Williamsburg ahead of his troops and warmly greeted Lafayette - like the son he never had. With an inferior force, Lafayette was occupying the narrowest part of the Peninsula, three miles wide, and was blocking Cornwallis's escape. Unable to realize the danger that he was in, Cornwallis decided to remain in Yorktown after some probes toward Williamsburg. For the allies, time was limited as the hurricane season was coming to an end. De Grasse would soon be forced to return to the Caribbean to protect France's valuable sugar islands. Washington decided to make a personal visit to the admiral, and boarded a boat on College Creek for trip down the James to Hampton Roads. There, he, Gen. Knox, and Rochambeau met the admiral on September 18th and got assurances that the French navy would remain, at least for a while..

Not all of the arriving allied troops marched 450 miles. Some sailed from the northern end of the Chesapeake Bay to the James River, and some French troops arrived from the Caribbean. Many landed near here, where College Creek empties into the James River. These troops joined the troops marching overland and Lafayette's men at Williamsburg, which became a base for the operation. With the arrival of allied troops on September 20th, any hope that Cornwallis had for an escape overland was now dashed. If the French Navy continued to hold the mouth of Chesapeake Bay as promised, victory was nearly assured.

The combined armies moved from Williamsburg to Yorktown on the 28th. Having had little warning of the trap, and having received assurances as early as September 11th of help to arrive soon from New York, Cornwallis was now bottled up in Yorktown.

Yorktown Creek

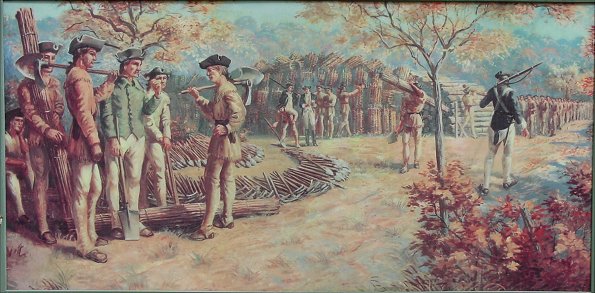

With a strong allied force several times his size approaching, Cornwallis hastened his efforts to entrench. The British works were still weak by the time the Allies arrived. Some people, then and now, believe that the British engineer in charge intentionally dragged out the process in order to line his pockets.

Fortunately for the British, much of Cornwallis' position was behind the swampy Yorktown Creek, shown above, which had steep cliff-like banks. This effectively prevented assault along most of his line, greatly simplifying the British defense effort.

Untouched Redoubt

Pigeon Hill Redoubt

Along the open front on the eastern side of Cornwallis' position, he built several outworks. In front of the right side of the exposed eastern portion of his defenses was built the Untouched Redoubt, which was abandoned, but also the Pigeon Hill Redoubt on slightly higher ground in front of his main defenses as well as a twin redoubt nearby. Because these works were weak, and because of promises of a relief expedition from Gen. Clinton, Cornwallis abandoned these outworks to the enemy with only a skirmish. Had he manned them, he may have been able to hold on long enough for help to arrive. There were also risks to this option, that of losing men needed for a successful defense, and the risk of his army being out-maneuvered or put into confusion outside of his strongest defenses.

Although the modern Pigeon Hill Redoubt is a reconstruction like many of the earthworks now at Yorktown, the Untouched redoubt is original.

Moore's Dam Over Wormley Creek

Cornwallis also had outworks built on his left, behind Wormley Creek, which empties into the York River east of Yorktown. These were not enclosed entrenchments but included abatis to their front - essentially felled trees. The dam and road shown here existed at the time. Downstream on the left of the panorama the creek flows into the York River, and behind the camera, further along the road, is the Moore house, which we will see later. The British forward position at the Pigeon Hill Redoubt was abandoned at least in part because of the threat of it being turned by an American advance here at Wormley Creek. On September 30th the works here and at Pigeon Hill were found empty by American troops. Next, we'll take a look up the arm of the creek visible on the right of the picture.

Wormley Creek Ravine

|

|

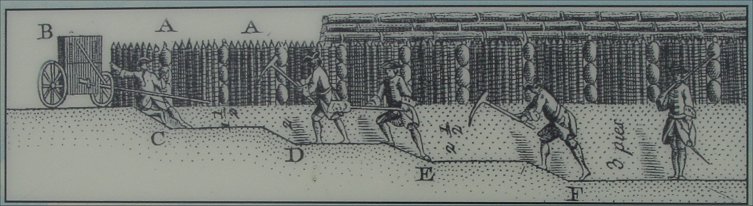

The picture above is looking down a sap which was dug forward at an angle from the 1st Parallel so that a second parallel could be dug closer to the British line.

This is a park service sign featuring an excerpt from a military manual which shows how a sap was dug. Dug at an angle to the enemy line, the enemy couldn't fire directly down the sap, but they would try to harass the work in any way possible. As it was dangerous work, and volunteers were used. These men drew extra pay which, at least in European wars, was often used to buy alcohol or the services of prostitutes. With a protective barrier being slowly rolled forward, the first man would begin construction. Follow-on workers made the trench deeper and wider and used the dirt to fill the wickerwork gabions above.