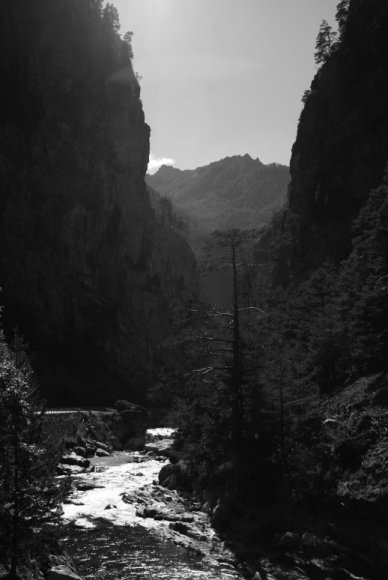

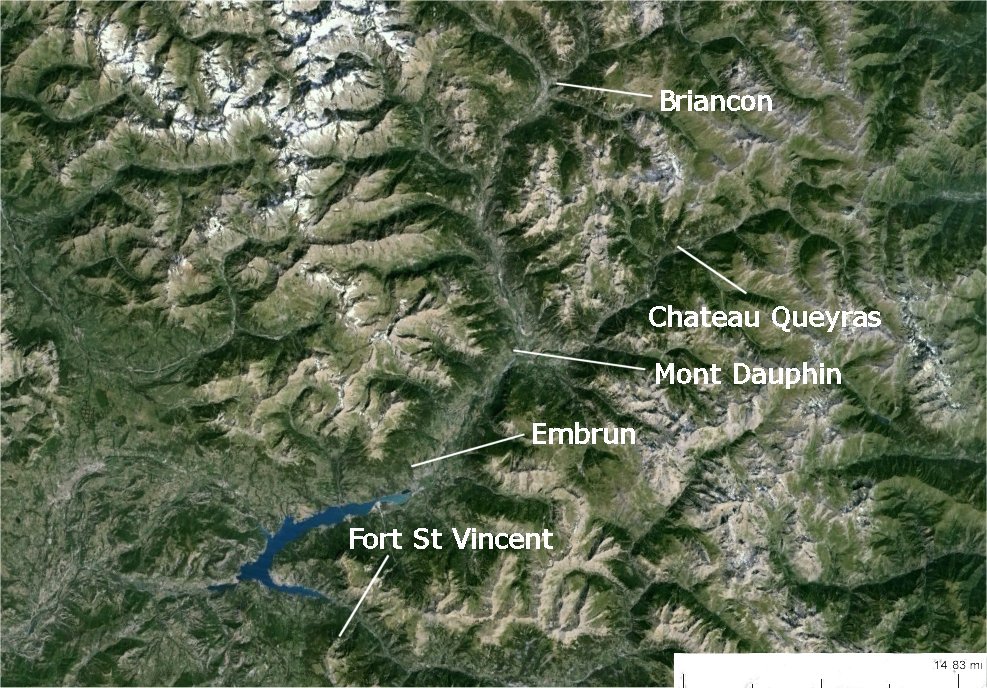

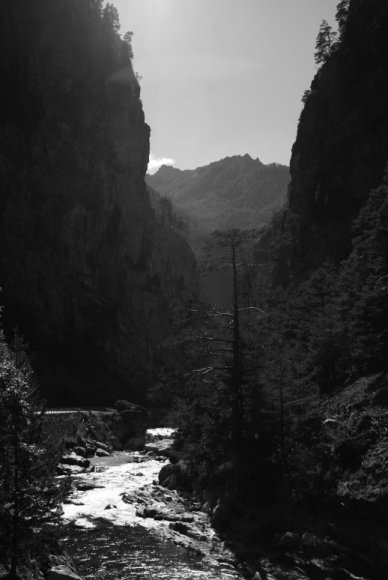

Gorge Between Chateau Queyras and Mont Dauphin

|

Gorge Between Chateau Queyras and Mont Dauphin |

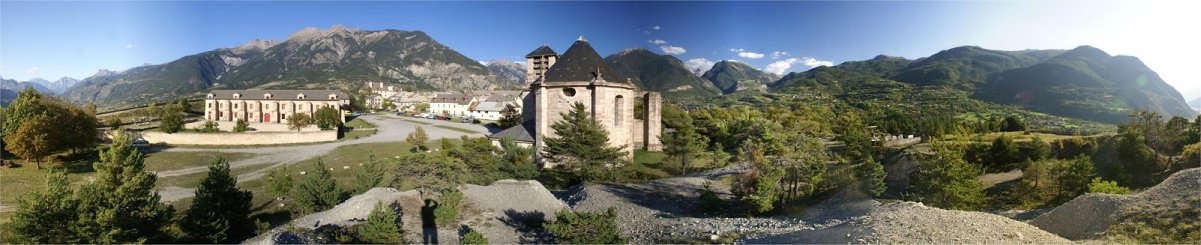

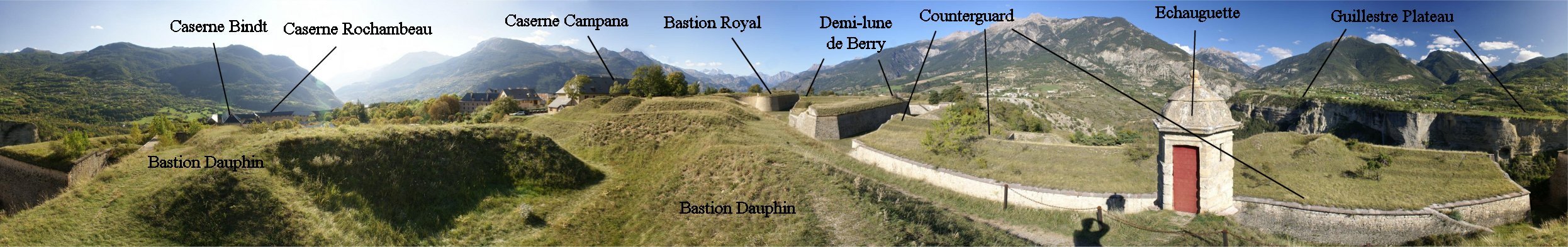

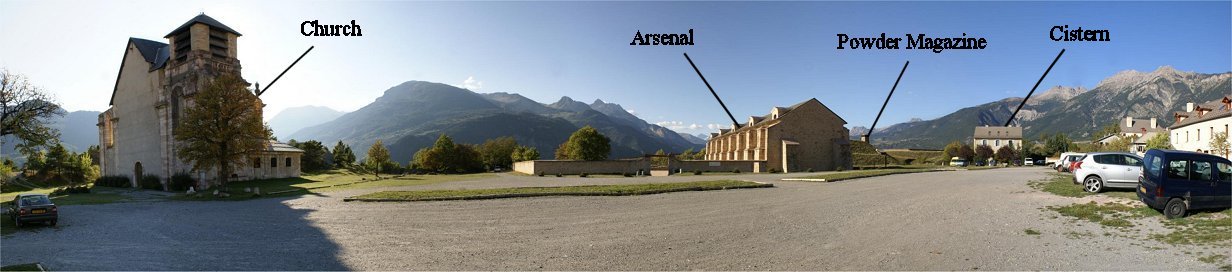

| The panorama above is the view from just inside

the southern gate, Porte

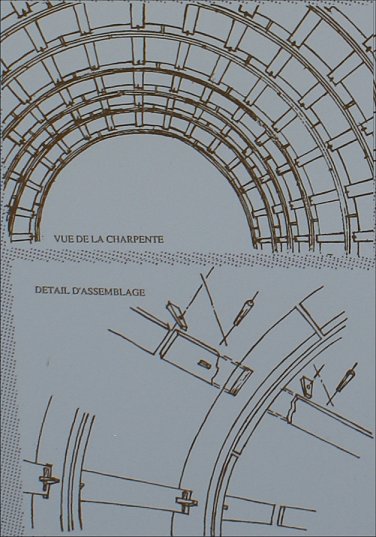

d'Embrun. Caserne Binot is a barracks perfectly adapted to the steep terrain on which it was built. In front of Caserne Binot is a cistern that could hold 1,840 cubic meters of water. In peacetime, water was collected in the mountains and piped into the fort, but this supply of water would have been cut during a siege. As a result it was necessary to store water in cisterns. The second, much larger cistern, the one here, was completed in 1730 and could hold two months worth of water. The oldest cistern is located near the powder magazine, and it could provide water to flood the magazine. At left is the "Plantation". It was created to provide shade and wood to the population and to the army. It included ash and lime trees, more resistant varieties. At right is the Caserne Rochambeau. Built from 1766 to 1783, the Caserne Rochambeau is a barracks built along the inside of the southern ramparts. It is a unique design inspired by a great architect of the 16th century, Philibert Delorme, who envisioned a system of assembling smaller parts. The building's wooden frame can be disassembled, and one man is able to handle each individual piece. With deforestation rampant, using small pieces was cheaper since long timber had become scarce and expensive. The design allowed for a large space that could be used for storage of materials or the training of troops. Also note the staircase to an upper floor atop a flying buttress. |

|

|

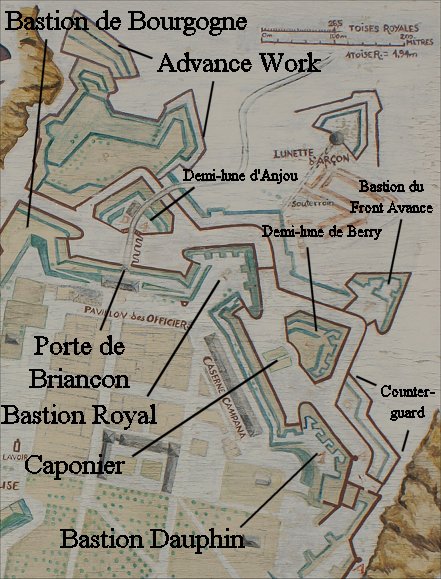

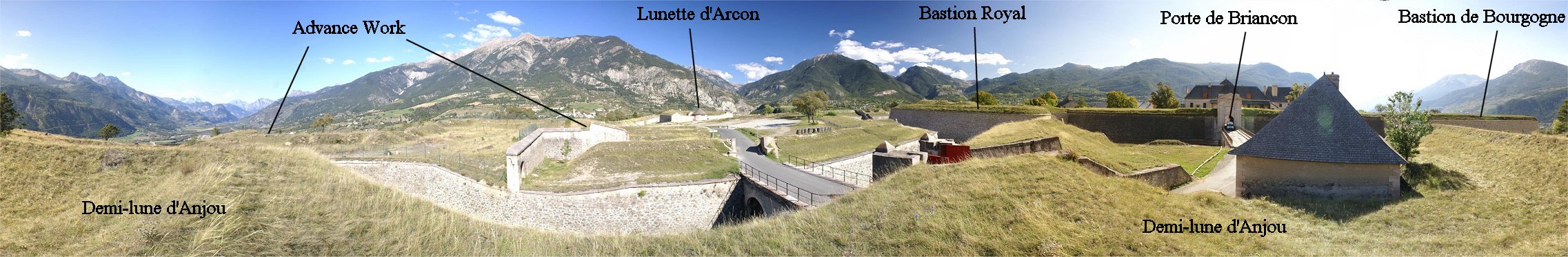

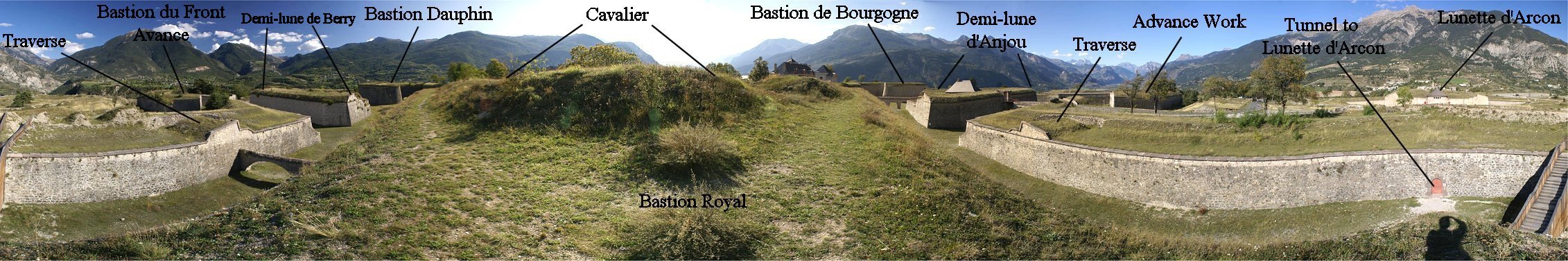

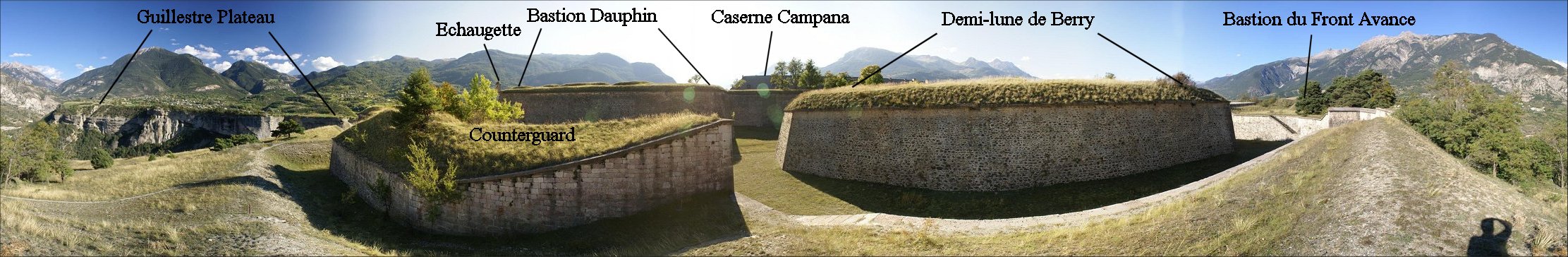

| The above panorama is of the front of the advance work, an

unusually shaped fortification that defies easy categorization.

Vauban was a believer that a geometrical 'cookie cutter' solution

was wrong in many cases, that the designer must adapt his design to the

terrain. The advance work is unusually shaped and includes terracing. It does not

easily fit into a category. Sadly this portion of the fortress was closed off during

my visit, preventing a more thorough investigation. Note: The two panoramas of the western face were made from beneath the western edge of the advance work. |

|

|

|

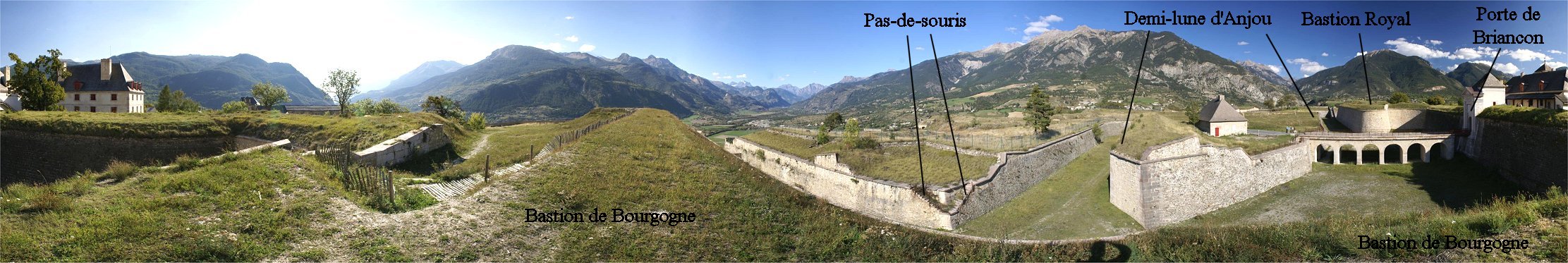

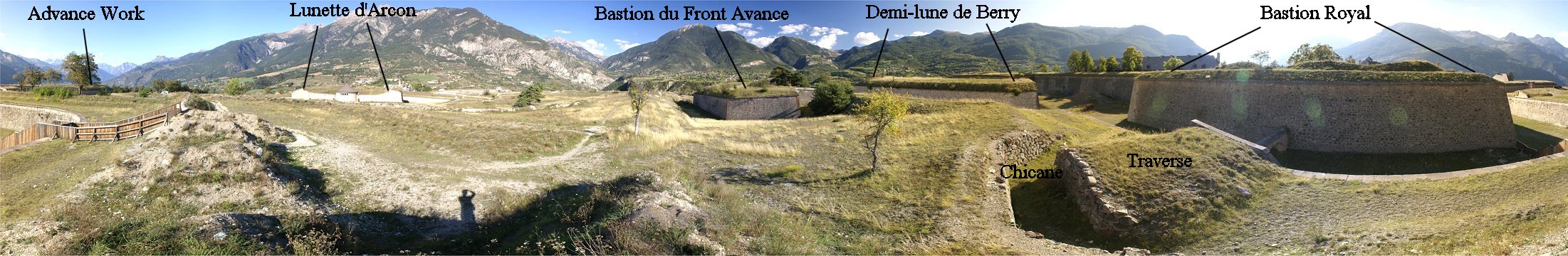

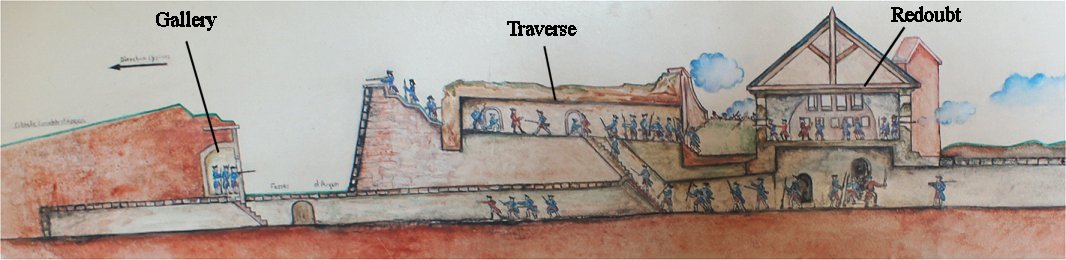

| A guardhouse greets visitor entering town from the north. Atop the Demi-lune d'Anjou can be seen the advance work, but little sense can be made of it. Several hundred yards in advance is the Lunette d'Arcon. |  |

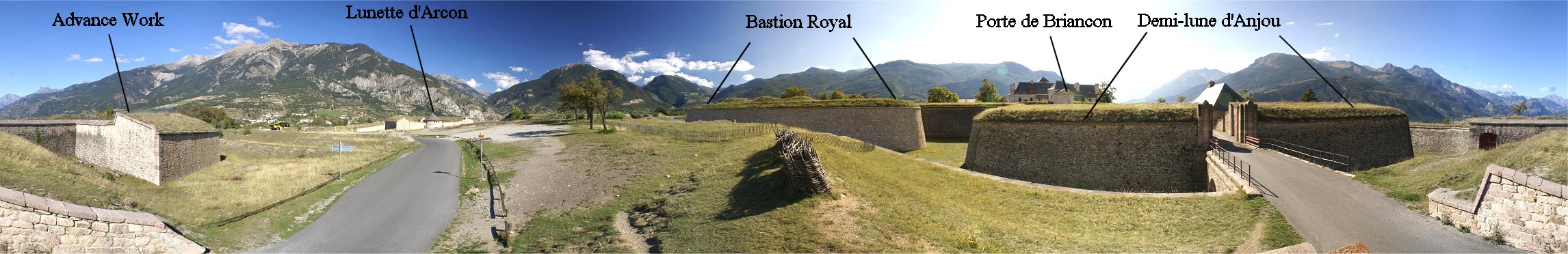

| This is the view from just in front of the Demi-lune d'Anjou. Wickerwork gabions are visible here. These were used like sandbags by a besieger as they advanced their trenches toward a fortress. In this case they and nearby trenches were dug in 2007 to try to study siege techniques. |  |

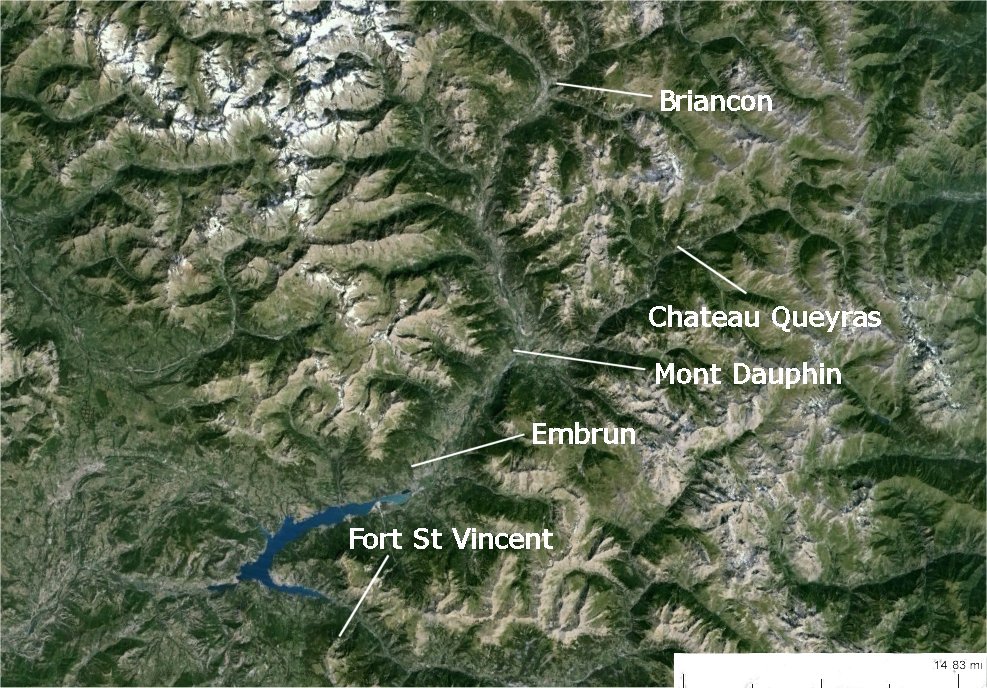

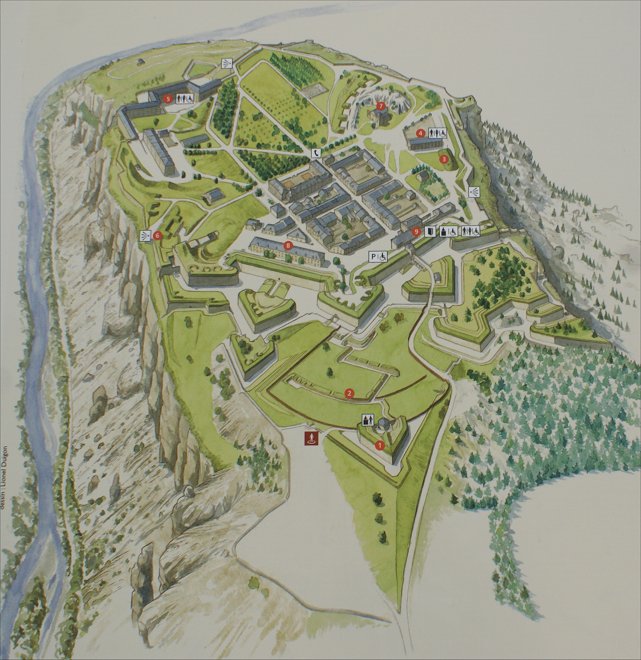

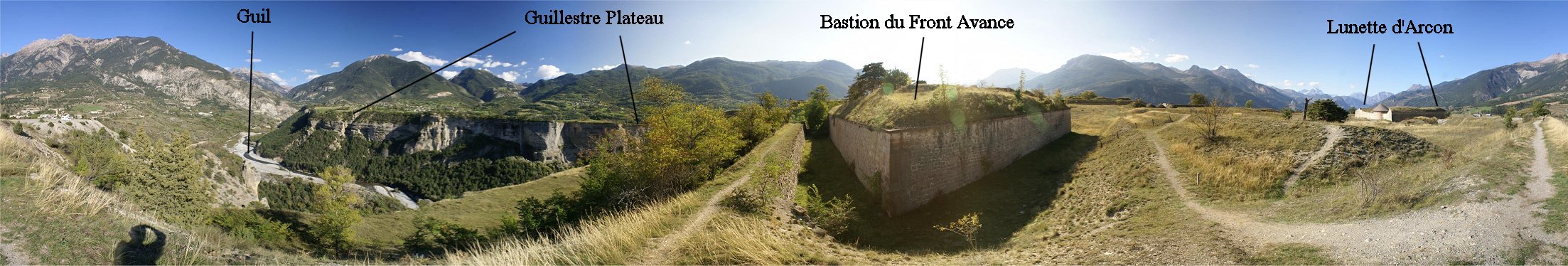

| Much of the fortress is visible from the eastern bastion, which is protected by a counterguard. A sentry post, or echauguette, overlooks it and across the Guil gorge to the Guillestre Plateau. Improvements in artillery technology made enemy occupation of this plateau a danger to the fort. Vauban designed defenses for this plateau, but they were never built. (See map at right.) Not clearly distinguishable here, the Bastion du Front Avance is forward of the Demi-lune de Berry. Inside the fortress several barracks can be seen, with the Caserne de Rochambeau along the fortress's southern rampart. The Caserne Campana was built in 1695 to partially house some of the troops building the fort. |  |

The waterfall is not natural. It is the discharge from a waterway diverted for irrigation. |

|

|

|

|