So what was the root cause of these supply problems?

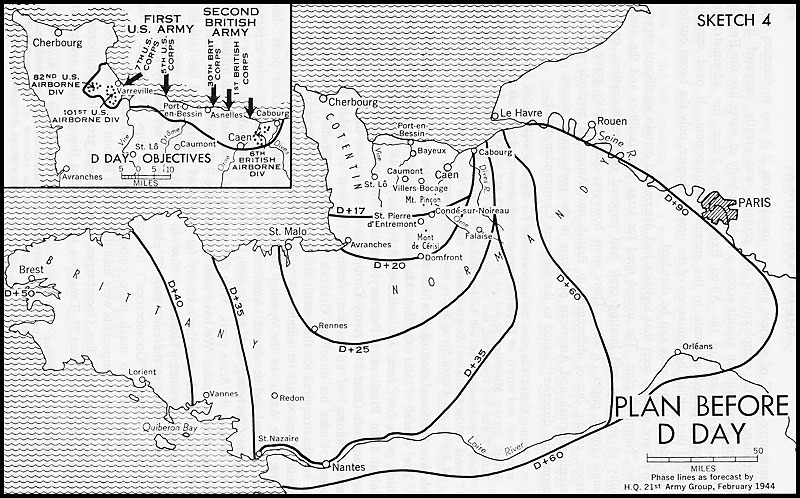

Phase lines had a profound impact on supply. In an April 7,

1944 meeting

at St Paul's School in London, Montgomery unveiled his planning maps

complete with phase lines.

Omar Bradley had prevously asked Monty to eliminate the phase

lines, and he again objected, stating that they limited iniative and

could harm troop morale if the men discovered that

they were behind schedule, but Monty assured everyone that the phase

lines were

simply for planning - created because it was American standard

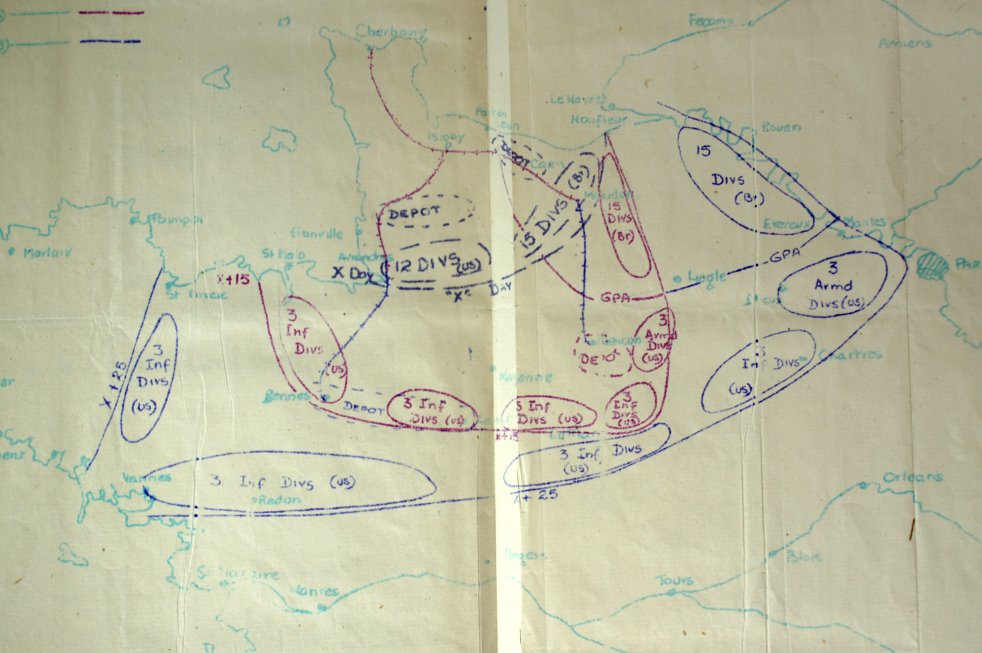

procedure, so the phase lines remained. The plan

foresaw fighting German reserves, but it did not envision a decisive

battle west of the Seine. They assumed that the Germans would

fall back and defend river crossings. As the projected advance

progressed, the battle lines became longer - but a potential thinning

of the German line

and a resulting Allied breakthrough was not foreseen. It was

not part of

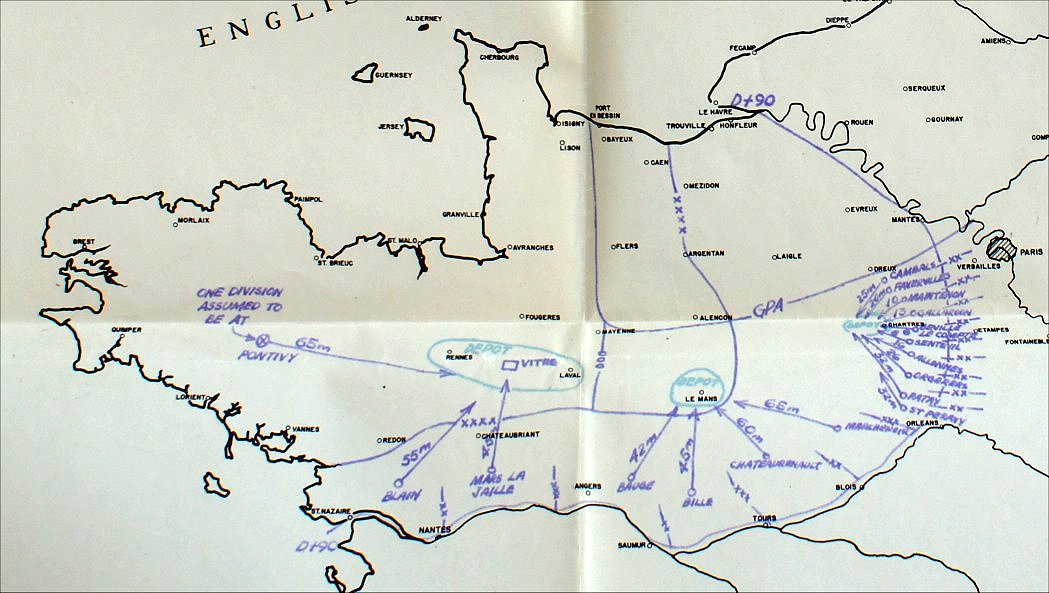

the plan, and it was not planned for. The plan was to halt at D+90 for a month at the Seine in order to

consolidate and prepare for an advance on to Germany. On

D+120, the US advance would continue after an advance base had been

established in the

Rennes-Laval area with a subsidiary base near Chartres-LeMans.

Plans and projections continued up until D+350, but they became

much more vague with time. Planning had been made for a lodgement but not for an advance afterward.

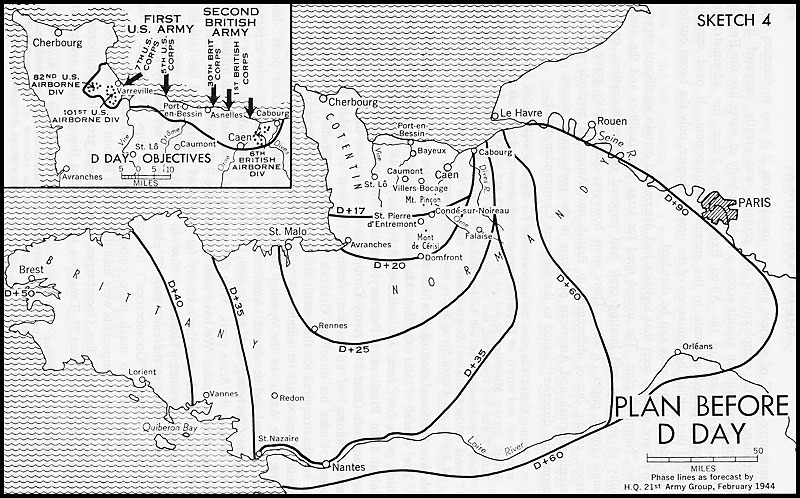

Although Montgomery claimed that the phase lines would not limit

the advance, they were used to plan supply - and so in effect they DID

limit the advance. The phase lines were the basis for the number

of transportation companies, the number of port clearance

units, the number of railroad repair units, and the number of road

repair units. If the advance went as planned, there would be

trucks, port clearance units, road repairmen, and railroad repairmen

when they were needed. If the advance was slower than planned, men would

be idle. But if the advance was quicker than

planned, there would not be enough trucks, not enough road

repairmen, not enough

railroad repair men, and not enough men to open up the ports. It

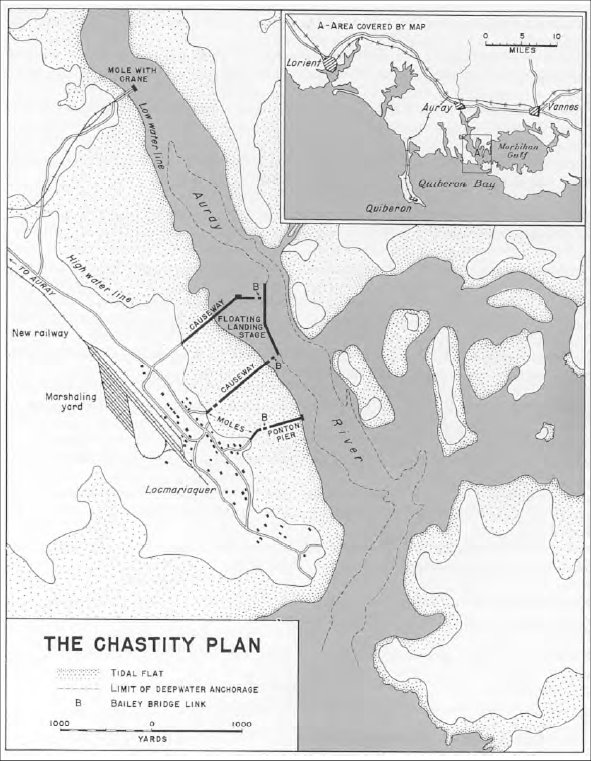

was the projected slow rate of advance that assumed a

relatively late liberation of the Seine ports, making the Breton

ports so important.

Only four years before, the Germans had broken through at Sedan and

improvised a quick and impressive advance to the Channel coast then

across France. In Russia, advances were sometimes made quickly. In

the deserts of North Africa, advances could come quickly. Why did the Allied plan

for northwest Europe not foresee that an Allied army could do the same? Allied thinking

was still rigid and methodical in this regard, little different than the mentality of a First World War

general. Although both British and American armies aspired to be flexible and adaptable, both armies

often followed, especially at higher levels, a kind of directive command where the general manages

and controls. In directive command, subordinates are not trusted

to make the right decisions. Both armies had made attempts to

copy the German system, where subordinates are told what to do but

given the freedom to decide how. The subordinate helped advise

the commander, and his views were respected. The Allied high

command showed a top-down mentality. It was warned that

logistical plans were faulty, but they did not listen. The

consequences were severe, with many men dying as a result. The root cause

was an outdated

command philosophy and the poor decisions that came from it. |

|