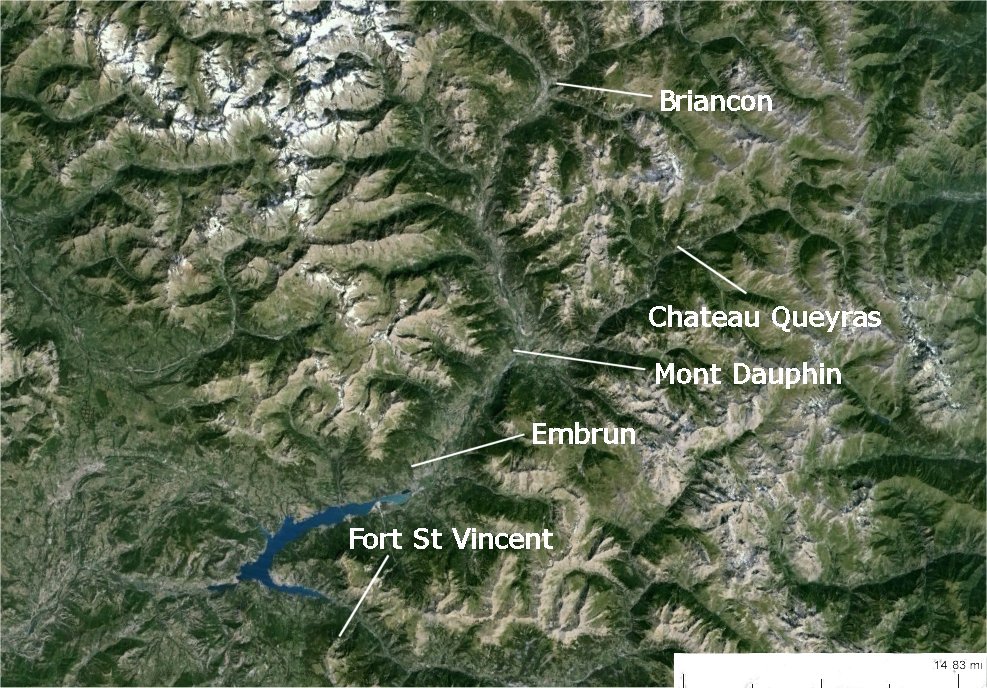

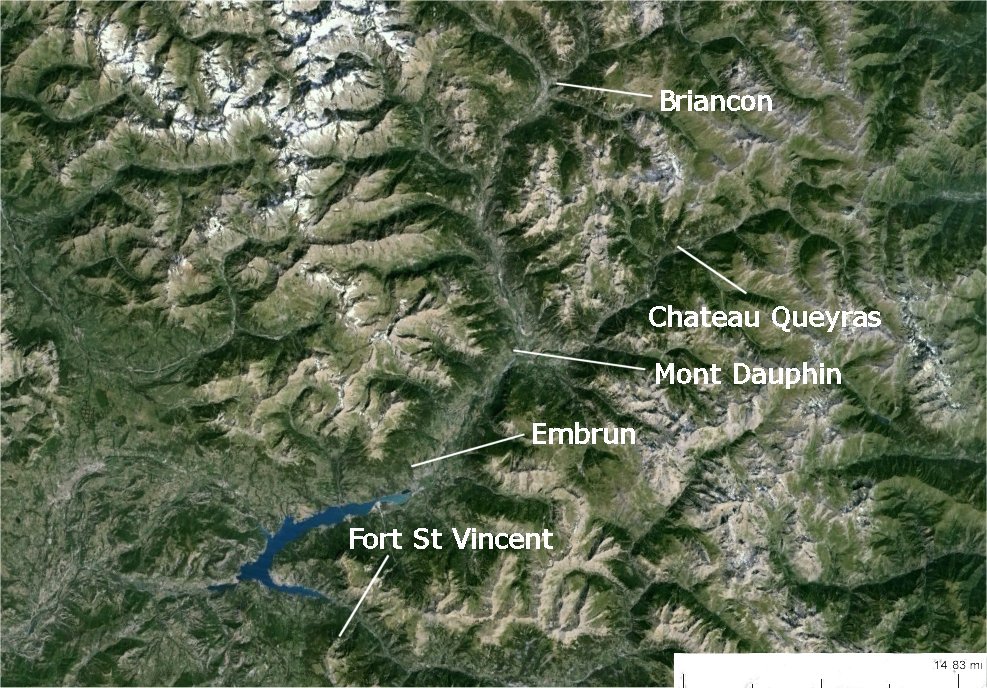

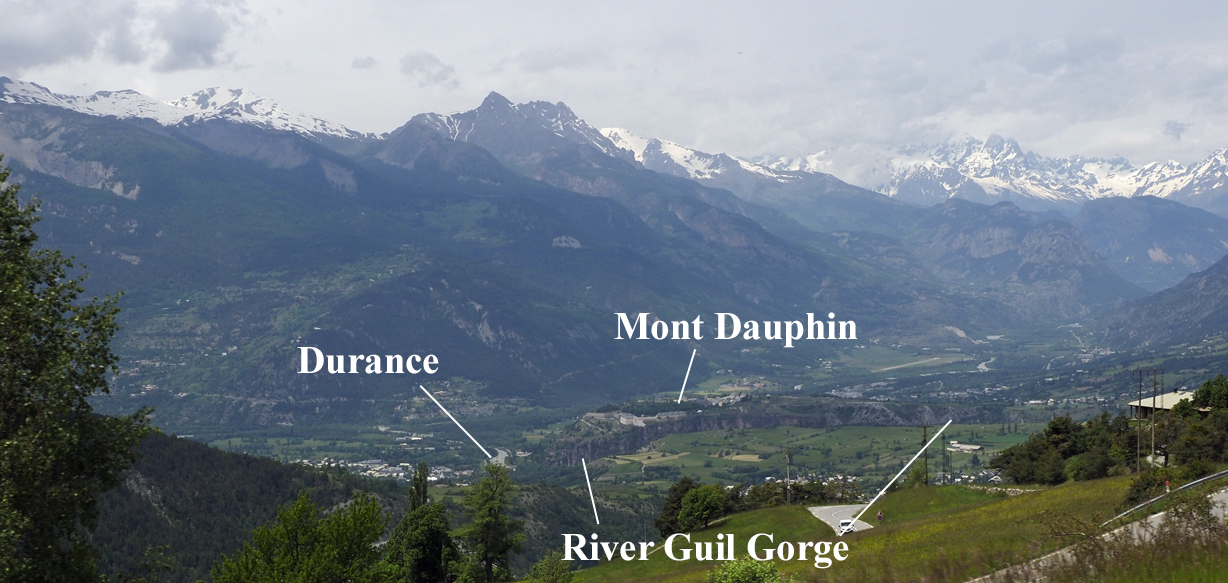

Gorge Between Chateau Queyras and Mont Dauphin

|

Gorge Between Chateau Queyras and Mont Dauphin |

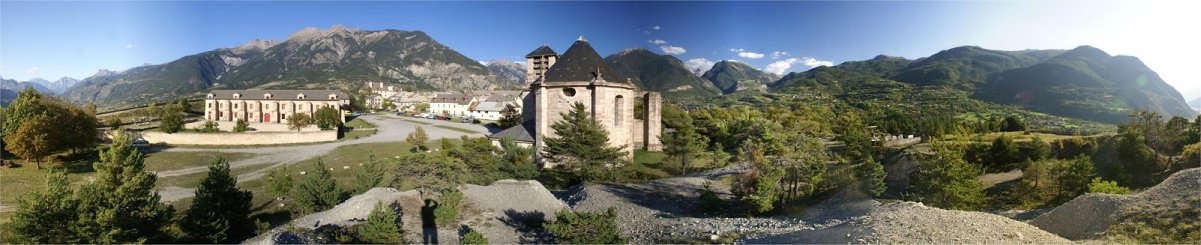

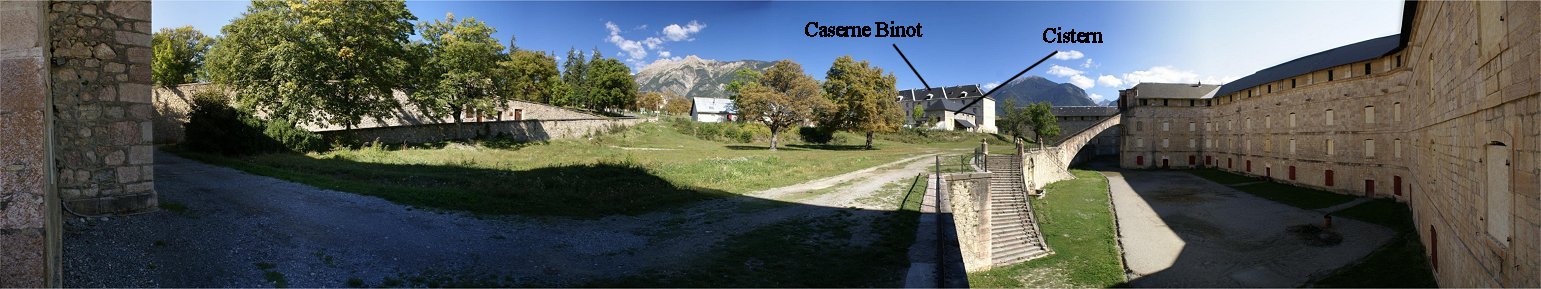

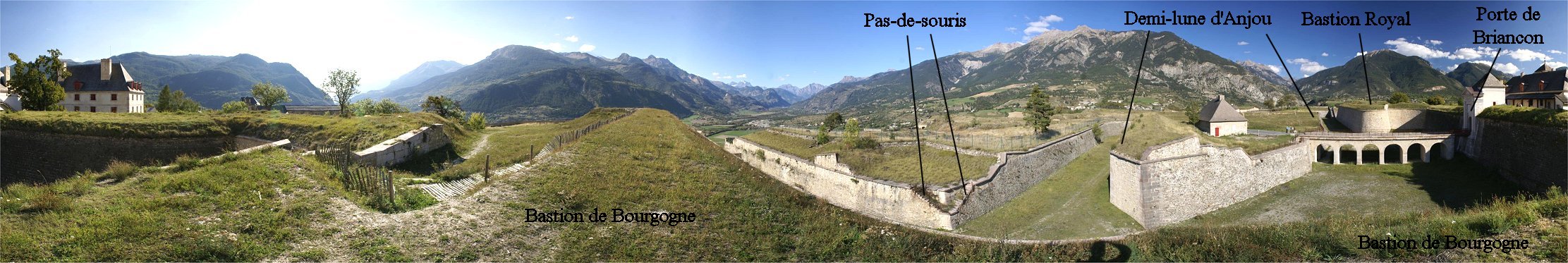

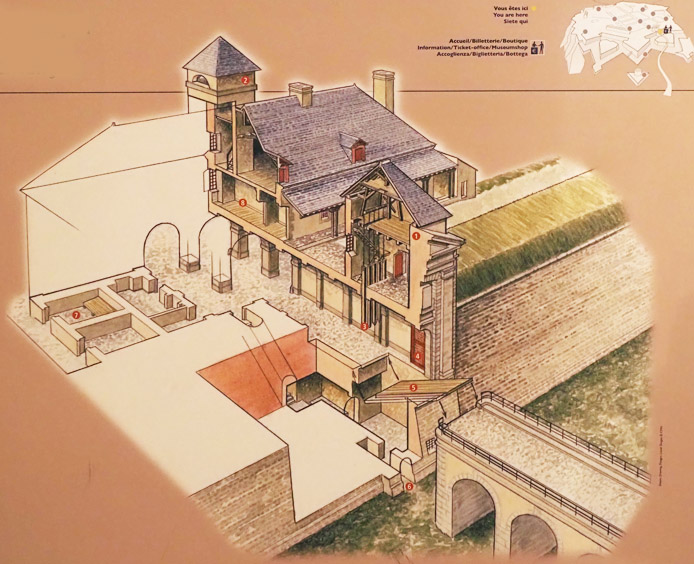

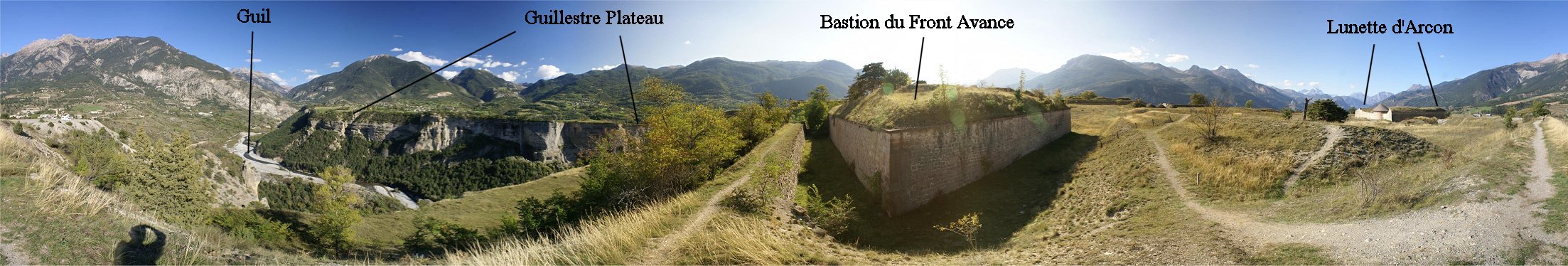

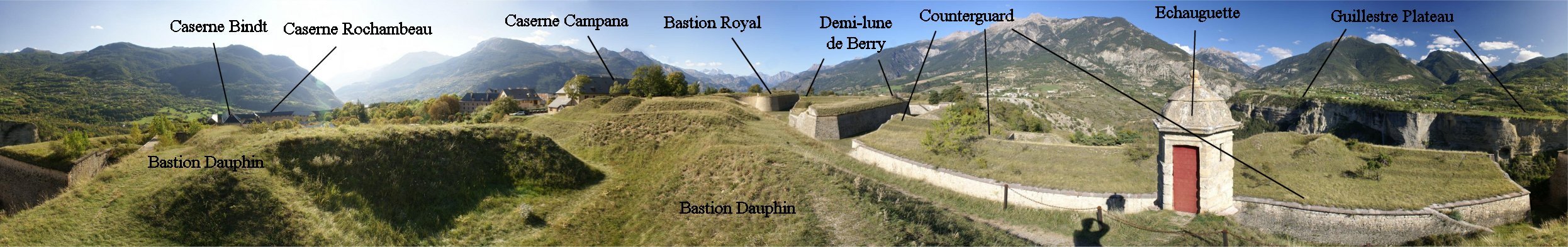

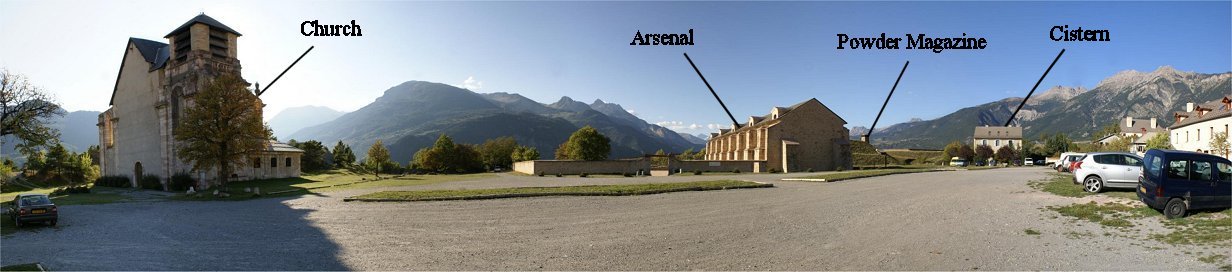

| The panorama above is the view from just inside

the southern gate, Porte

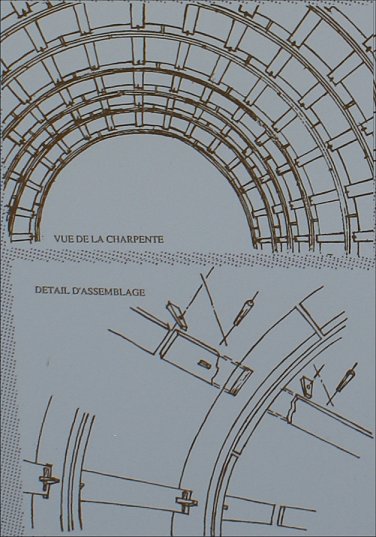

d'Embrun. Caserne Binot is a barracks perfectly adapted to the steep terrain on which it is built. In front of Caserne Binot is a cistern that could hold 1,840 cubic meters of water. In peacetime, water was collected in the mountains and piped into the fort, but this supply of water would have been cut during a siege. Rainwater and melted snow could also be stored in the fortress's cisterns. As a result it was necessary to store water in cisterns. The second, much larger cistern, the one here, was completed in 1730 and could hold two months worth of water. The oldest cistern is located near the powder magazine, and it could provide water to flood the magazine in case the fortress was taken. At left is the "Plantation". It was created to provide shade and wood to the population and to the army. It included ash and lime trees, more resistant varieties. An additional benefit was that the trees helped mitigate the strong winds which are known to affect the area. At right is the Caserne Rochambeau. Built from 1766 to 1783, the Caserne Rochambeau is a barracks built along the inside of the southern ramparts. It is a unique design inspired by a great architect of the 16th century, Philibert Delorme, who envisioned a system of assembling smaller parts. The building's wooden frame can be disassembled, and one man is able to handle each individual piece. Using small pieces was cheaper since long timber had become scarce and expensive. The wood used was larch, a tree native to the area which has needles that turn color and fall off in the autumn. The design allowed for a large space that could be used for storage of materials or the training of troops in winter. This wooden roof was built between 1819 and 1823. Also note the exterior staircase to an upper floor atop a flying buttress, a feature added in 1785 to help counter the weight of the building. The interior of Caserne Rochambeau was accessible only by guided tour. |

|

|

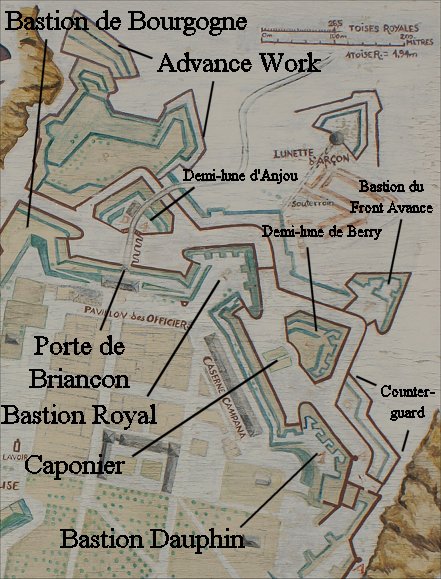

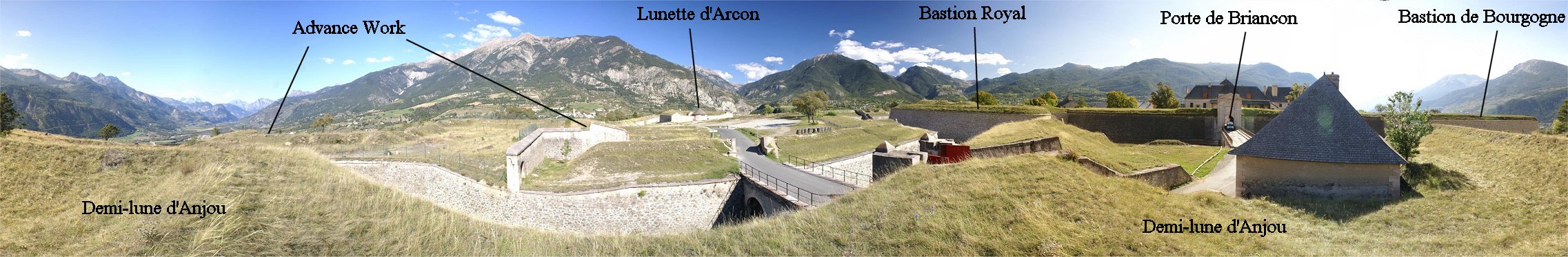

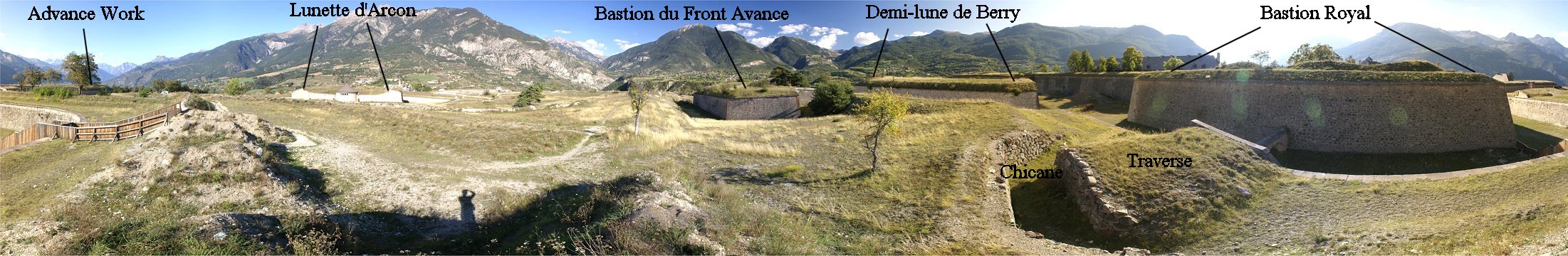

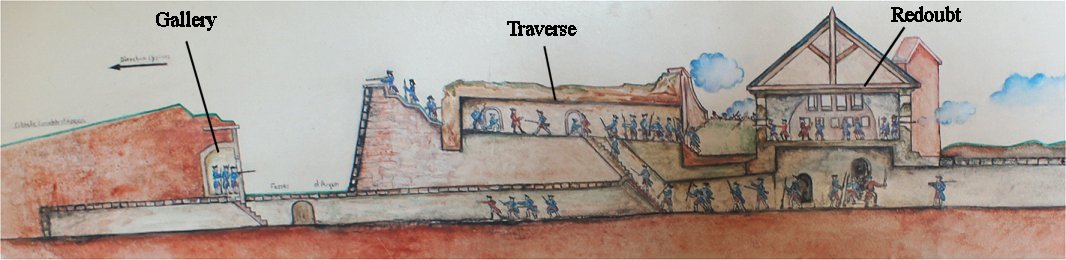

| The above panorama is of the front of the advance work, an

unusually shaped fortification that defies easy categorization.

Vauban was a believer that a geometrical 'cookie cutter' solution

was wrong in many cases, that the designer must adapt his design to the

terrain, so this outwork seems designed in that spirit, but it dates to the late 1800s. The advance work is unusually shaped and includes terracing. It does not

easily fit into a category. Sadly this portion of the fortress was closed off during

my visit, preventing a more thorough investigation. Note: The two panoramas of the western face were made from beneath the western edge of the advance work. |

|

|

|

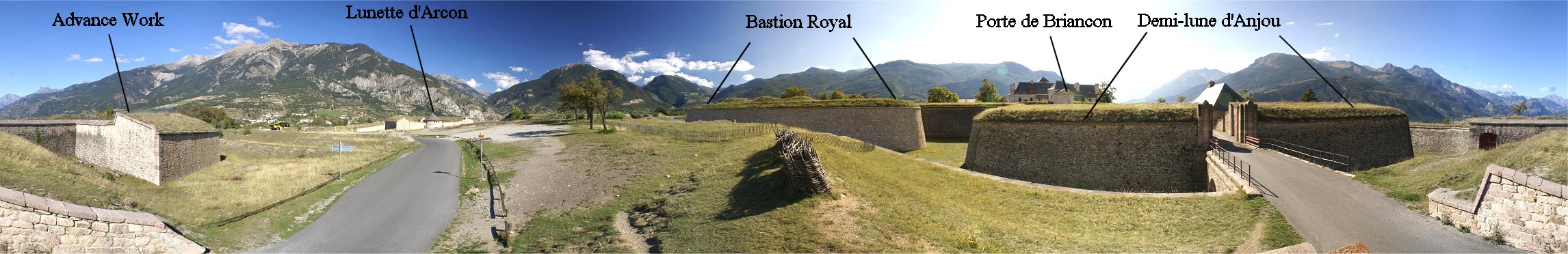

| A guardhouse greets visitor entering town from the north. Atop the Demi-lune d'Anjou can be seen the advance work, but little sense can be made of it. Several hundred yards in advance is the Lunette d'Arcon. |  |

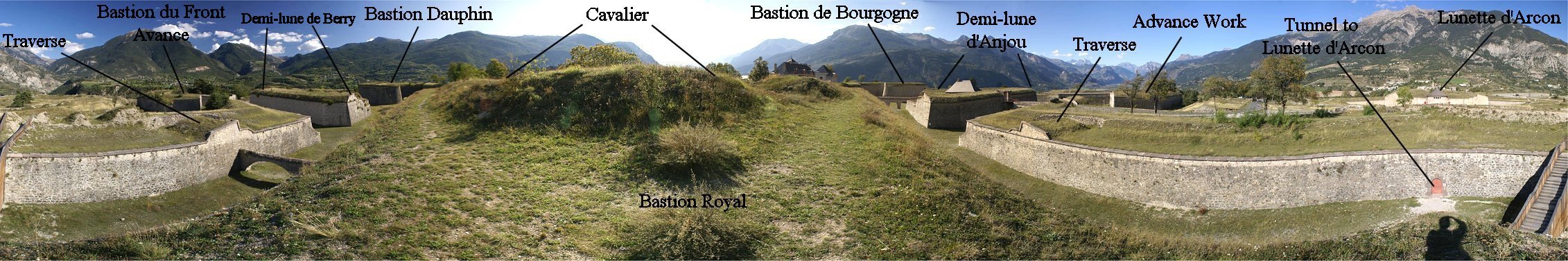

| This is the view from just in front of the Demi-lune d'Anjou. Wickerwork gabions are visible here. These were used like sandbags by a besieger as they advanced their trenches toward a fortress. In this case they and nearby trenches were dug in 2007 to study siege techniques and also destroy the remains of a 1939 artillery work. |  |

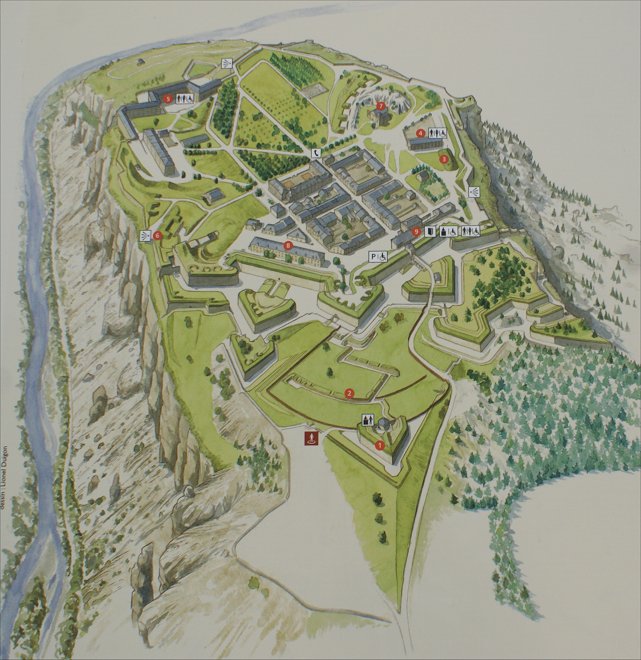

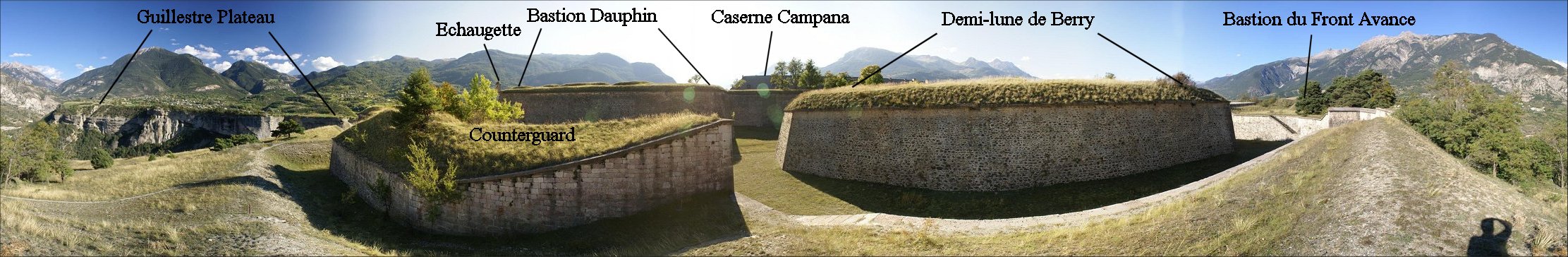

| Much of the fortress is visible from the eastern

bastion, which is

protected by a counterguard. A sentry post, or echauguette,

overlooks

it and across the Guil gorge to the Guillestre Plateau.

Echauguettes gave hints to besiegers were angles existed in the defenses,

so they were built without mortar so that they could be disassembled and

removed during a siege. Vauban designed defenses for the plateau across the Guil gorge, but they were never built. (See map at right.) It would have been an expensive and difficult project that would have involved spiral staircases cut through the rock, used to access the valley floor but also serving as wells. Even had this been done, communication by bridge across the river would have been vulnverable to enemy fire. Not clearly distinguishable here, the Bastion du Front Avance is forward of the Demi-lune de Berry. Inside the fortress several barracks can be seen, with the Caserne de Rochambeau along the fortress's southern rampart. The Caserne Campana was built in 1695 to partially house some of the troops building the fort. |

|

The waterfall is not natural. It is the discharge from a waterway diverted for irrigation. irrigation canals are common in the mountains of France. |

|

|

|

|