In the early days of the Great War, a German advance created a salient

south of Verdun, and with the onset of trench warfare, the

salient became a permanent thorn in Verdun's flank. Soon

after the American declaration of war, US Army officers searched for a

role on the Western Front, and reducing the St Mihiel salient seemed

like a worthy challenge useful to the war effort. Reducing the salient was also a stepping

stone toward an advance on the German communication center at Metz

where an important rail line passed, a rail line that supplied the

German army on the most active part of the Western Front.

With Russia knocked out of the war in 1917, the Germans shifted troops to the Western Front and launched a series of offensives against the British and French armies. By July these offensives were stopped, and on July 18th a Franco-American counterattack at Soissons pushed back the Germans. On August 8th, an Anglo-French counterattack gained great success, and hope flowered that victory could be achieved in 1918 with a concentric attack by all the armies, including the US Army in the Meuse-Argonne. But the most experienced American divisions were already slated to attack the St. Mihiel Salient. In heated discussions between Generalissimo Foch and John J Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force, it was agreed that the Americans would conduct both the St. Mihiel Offensive and the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

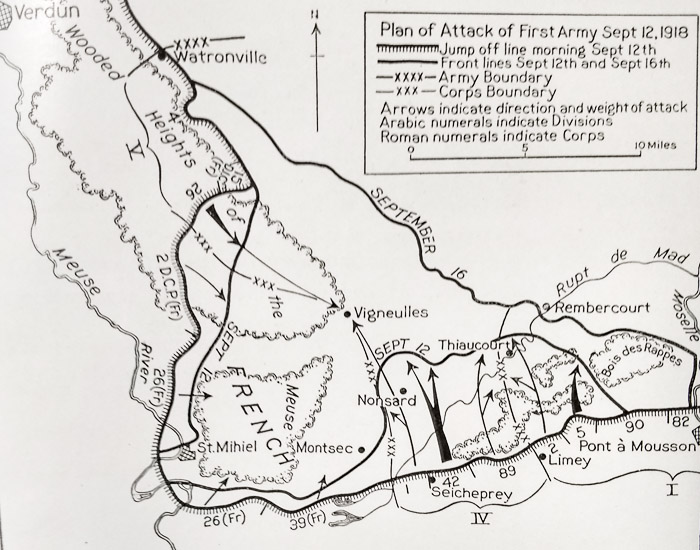

Diversionary efforts far to the south at Belfort near the Swiss border were made in the hopes that the Germans would shift troops there. Meanwhile, Swiss newspapers had learned of the upcoming St. Mihiel Offensive and reported it. When it came, there was no operational surprise. About 110,000 French troops supported 550,000 American (216,000 of them on the frontlines), which combined outnumbering the Germans by about eight to one. An unprecidented 1,481 planes supported the offensive, along with 400 tanks and 3,000 guns, but 2 of 3 American corps headquarters had never conducted an offensive and the same was true for 4 of 14 American divisions. Three of the 14 US divisions were in army reserve, and both I and IV Corps each had a division in reserve. This would be the first offensive by a US Army in the war, an important milestone. At the salient, while French divisions pinned down Germans near the tip at St. Mihiel, the US 26th Division would attack the hilly western face of the salient toward Vigneulles, where they would link up with the primary effort attacking the south face of the salient, which was on terrain more suitable for attack.

With the success of the Allied counterattacks in July and August, the Germans were short of troops, and the St Mihiel salient had lost its importance. Straightening the line would shorten the front by 60 km (about 37 miles), free up four divisions, and put the line on the Michel Zone, an extension of the Hindenberg Line. Plans to evacuate the salient were drafted, and evacuation of rear areas was underway when the offensive was launched. Heavy artillery had mostly withdrawn, and orders were to fight a rear guard action.

With Russia knocked out of the war in 1917, the Germans shifted troops to the Western Front and launched a series of offensives against the British and French armies. By July these offensives were stopped, and on July 18th a Franco-American counterattack at Soissons pushed back the Germans. On August 8th, an Anglo-French counterattack gained great success, and hope flowered that victory could be achieved in 1918 with a concentric attack by all the armies, including the US Army in the Meuse-Argonne. But the most experienced American divisions were already slated to attack the St. Mihiel Salient. In heated discussions between Generalissimo Foch and John J Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force, it was agreed that the Americans would conduct both the St. Mihiel Offensive and the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

Diversionary efforts far to the south at Belfort near the Swiss border were made in the hopes that the Germans would shift troops there. Meanwhile, Swiss newspapers had learned of the upcoming St. Mihiel Offensive and reported it. When it came, there was no operational surprise. About 110,000 French troops supported 550,000 American (216,000 of them on the frontlines), which combined outnumbering the Germans by about eight to one. An unprecidented 1,481 planes supported the offensive, along with 400 tanks and 3,000 guns, but 2 of 3 American corps headquarters had never conducted an offensive and the same was true for 4 of 14 American divisions. Three of the 14 US divisions were in army reserve, and both I and IV Corps each had a division in reserve. This would be the first offensive by a US Army in the war, an important milestone. At the salient, while French divisions pinned down Germans near the tip at St. Mihiel, the US 26th Division would attack the hilly western face of the salient toward Vigneulles, where they would link up with the primary effort attacking the south face of the salient, which was on terrain more suitable for attack.

With the success of the Allied counterattacks in July and August, the Germans were short of troops, and the St Mihiel salient had lost its importance. Straightening the line would shorten the front by 60 km (about 37 miles), free up four divisions, and put the line on the Michel Zone, an extension of the Hindenberg Line. Plans to evacuate the salient were drafted, and evacuation of rear areas was underway when the offensive was launched. Heavy artillery had mostly withdrawn, and orders were to fight a rear guard action.