Harpers Ferry

September 12-15, 1862

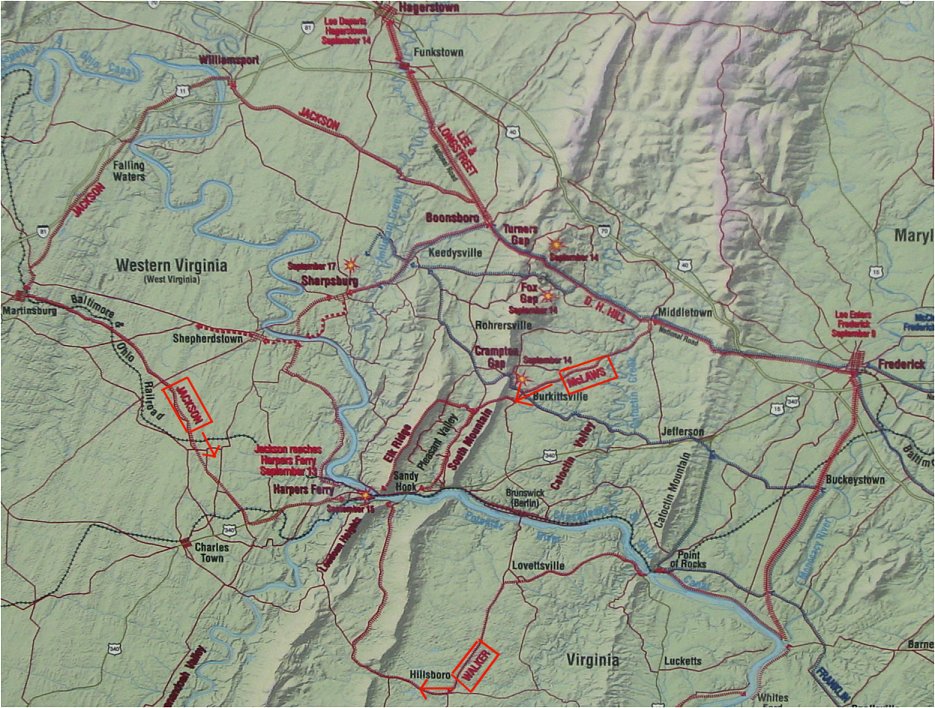

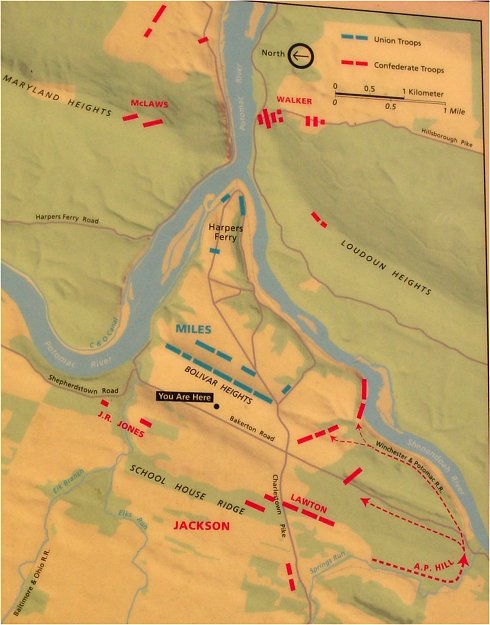

With victories in the Seven Days and Second Manassas Campaigns, the Confederate capital of Richmond was now safe, and momentum had shifted toward the Confederacy. In order to maintain that momentum, and to potentially bring Maryland into the Confederacy, Lee sent his army north across the Potomac. His plans to advance into Pennsylvania were stymied by a quicker than expect reaction from the usually slow George McClellan. Another problem was the 14,000 man Union garrison of Harpers Ferry, site of the old arsenal. Surrounded by mountains which dominated the place, and now in the Confederate rear, logic dictated a Union withdrawal from the place. Civil War commanders didn't always follow logic, however, and the garrison remained. For the Confederates, the prospect of capturing the Yankee troops in the town was enough of a lure, but Lee also had to establish safe lines of communication through the Shenandoah and Cumberland Valleys. To bag the Yankees, on September 10th Lee dispatched a sizeable portion of his army to capture the place, and most of them had to re-cross the Potomac. If the operation was delayed, or if it failed - or if McClellan simply moved quickly - Lee's relatively small army could be easily defeated in detail. It would be one of Lee's greatest gambles.

Walker's Division, around 2,000 men, re-crossed the Potomac near where Lee's army had crossed into Maryland just days before and moved toward Loudon Heights. Without re-crossing the Potomac, 8,000 men of McLaws' Division moved toward Maryland Heights while the main striking force of 14,000 men under Jackson took a circuitous route through Williamsport to re-cross the Potomac, then marched through Martinsburg in order to close the final potential Union escape route. The rest of Lee's army remained on the defensive in Maryland.

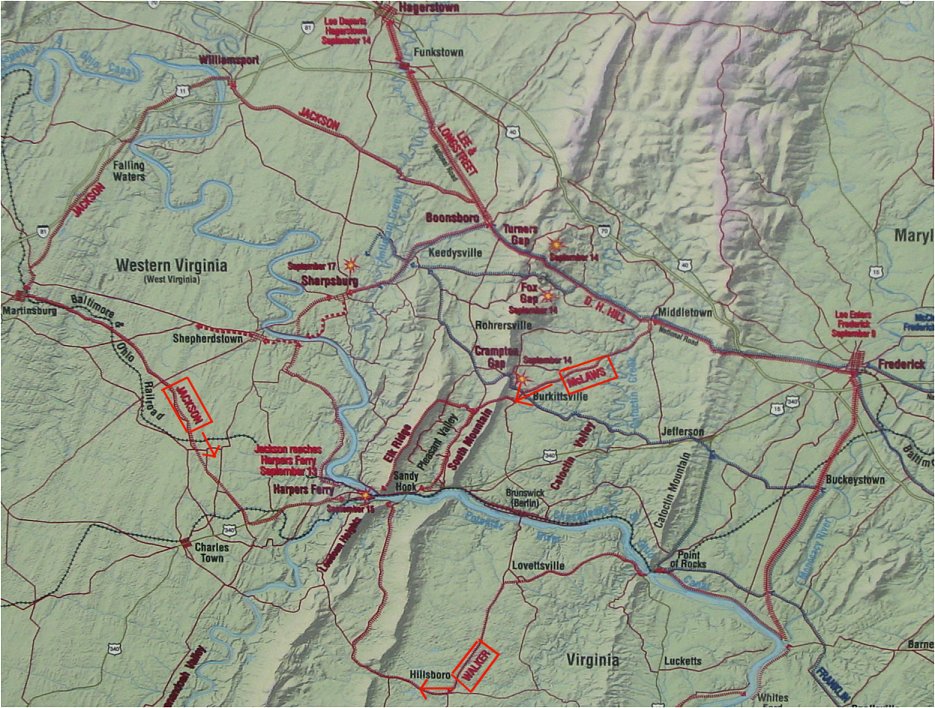

From Bolivar Heights

A successful Union defense of Harpers Ferry required that Bolivar Heights to the west of town be held. This panorama was taken from the heights, which you can see from descending road - but more clearly by scrolling tot he right to see a side view of the ridge. As you can see, Bolivar Heights dominated Harpers Ferry. Camp Hill, closer to town, can be seen beneath the cut in the mountains, where the Potomac passes through the Appalachians. Maryland Heights on the left was the target of McLaws' Division. Across the Shenandoah River, Loudon Heights to the right of the cut was the objective of Walker's Division. Jackson himself would face Bolivar Heights.

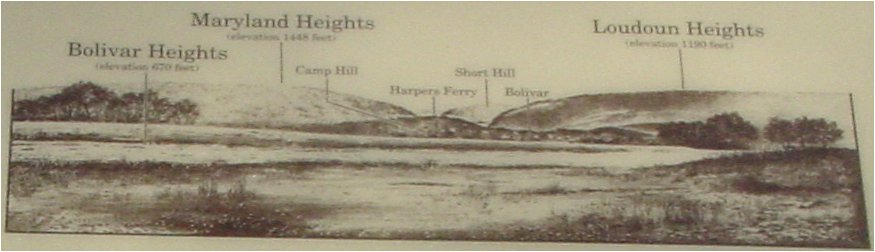

Bolivar Heights From Schoolhouse Ridge

Jackson faced the Union position from Schoolhouse Ridge and set up batteries there, an area which has been preserved with help from the CWPT. As you can see, Bolivar Heights is 200 feet higher than Schoolhouse Ridge, giving the Union garrison a strong defensive position as well as the ability to see Confederate movements.

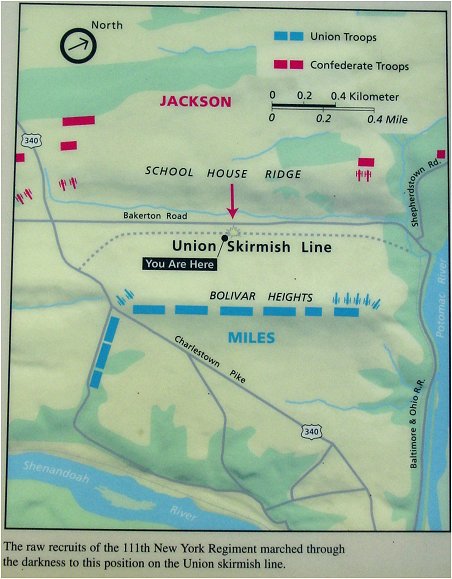

From Lower Slopes of Bolivar Heights Looking Toward Schoolhouse Ridge

Near the foot of the heights, along the modern road, Union skirmishers clashed with the Confederates. A quick walk up to the modern woods on Bolivar Heights shows that this area is roughly level with the Confederate position on Schoolhouse Ridge. It had to have been obvious to Jackson that a frontal assault on the Union position would be costly. However, with the Union Army of the Potomac on the march in Maryland, a prolonged siege was impossible. With Lee's main army in grave danger, Jackson needed a quick victory.

From Bolivar Heights - Again

Walker captured Loudon Heights unopposed, and McLaws took Maryland Heights after a short fight on September 13th, and artillery was brought up to the high ground to bombard the garrison. It began firing the next day. All told, 50 Confederate guns fired on the Yankees, but still they resisted surrender. Alternatives to a direct assault on Bolivar Heights did exist. The Union position on the heights wasn't as safe as it might have seemed. In the panorama above, which we've seen before, you can see that behind Bolivar Heights toward Loudon Heights, the ground descends and flattens on the way to the Shenandoah River. This area was virtually undefended, with only abatis as a barrier. |

|

View From AP Hill's Position - an area newly preserved by the CWPT

Union troops were shuffled from behind Bolivar Heights to face the new threat to their flank posed by AP Hill, but they were vulnerable to enfilade fire from Loudon Heights, on the mountain range on the right of the picture. Jackson had ordered 10 guns from Schoolhouse Ridge across the Shenandoah River unto the lower slopes of the height. Under bombardment in town, the Union commander, Col. Dixon Miles, was mortally wounded. Before the fight on the flank even developed, the new Union commander saw the writing on the wall. Although time was vitally important to the Union cause, a successful Confederate assault would have been a bloody affair for the Union troops. Surrender was the only alternative. Although a few cavalrymen had escaped, Harpers Ferry would be the largest surrender of US Army troops until World War II.

Harpers Ferry From Maryland Heights

The cavalry escape had been a risky feat. On the night of September 14th, 1,300 Union cavalrymen under "Grimes" Davis escaped across a pontoon bridge over the Potomac and headed west along the foot of Maryland Heights. This is the area on the right of the picture. This area had been denuded of Confederates in order to deal with the threat to McLaws' rear posed by the advancing Federals near South Mountain, Federals whose mission was to relieve the garrison and bag the Confederate division. Indeed, the diverted rebel troops would prove invaluable at Crampton's Gap, helping save the Confederate operation at Harpers Ferry. On their way to joining the main Union army near Sharpsburg, the Yankee cavalry captured and burned a portion of Longstreet's wagon train.

While Lee was facing a much larger Union army at South Mountain, Jackson was able to wrap up his operation in time to rejoin the main army, leaving AP Hill to handle the clean up. Harpers Ferry had been an impressive Confederate success. Although the Confederate advance north had been delayed, then halted, a reinforced Lee made a stand behind Antietam Creek, thinking that more could be gained. September 17th would be the bloodiest single day of the war.

Back to Civil War Virtual Battlefield Tours